Text: Peter Tepe | Section: Articles by Artists

Abstract: Since the article Science-Related appeared in w/k, Peter Tepe has produced three new series that inspired him to explore a new connection between science and art under the title Structural Affinity. The following article introduces this new connection and outlines its relevancy to w/k.

The article Science-Related: Four New Series, published 16 December 2019, presents artworks that I produced in 2018/19. This was followed by Video Interview 1: Peter Tepe on 10 December 2020 by Riad Nassar and Till Bödeker: the two publications belong together. In this article, I present three new series that I made since 2020.

1. Structural Affinity: A new connection between science and art

The article 5 years w/k: what happened so far distinguishes six connections: science-related art (and its many subtypes), technology-related art, cooperations between science, technology and art, border crossers, art-related science and artistic research (and its various subtypes). I would now like to add a seventh connection: the structural affinity between scientific and artistic practice. In this article, I will present one variant of this connection in which the artistic approach adopts a certain technique used in the production of scientific texts.

In terms of series 1 and 2, the first of which is complete, I have been thinking about whether the corresponding artistic work has any reference at all to the topic of art and science. At first glance, this doesn’t seem to be the case. For instance, the images cannot be classified as either science-related art (where an artist draws on scientific theories/methods/results in the production process) or art-related science (where a scientist utilises artistic concepts/methods/results in the production process of their teachings, research or specialist publications). After a long process of reflection, however, I have come to the conclusion that there is indeed a new connection – in fact, one that has not yet been considered in art-and-science theory. I thus also use the presentation of my new works and the explanation of their underlying artistic concepts to fill a theoretical gap.

My thesis is as follows: the above-mentioned artistic work is a kind of art that shares a structural affinity with the working method I used in my scientific practice for many years. In this case, “working method” does not mean the application of a scientific method, but, more fundamentally, the technique of producing scientific texts. I developed the general artistic concept in the years 1989-1995; in some of my current series, I continue to follow this approach, and in others it varies in new ways.

Border Crossers

In w/k, we use the term border crosser between science and art to describe those individuals that have both an artistic and a scientific practice; I belong in this category. Several w/k contributions have featured two border crossers of outstanding importance: Herbert W. Franke and Karl Otto Götz; cf. 5 years w/k: what happened so far, Part II, Chapter 5. A structural affinity between one’s own scientific and artistic practice can only occur in border crossers: after all, one prerequisite is that they have an independent scientific practice. For such individuals, there are various different constellations:

Constellation 1: A border crosser makes science-related art of a special kind: their artistic activity ties in thematically, or in terms of content, with their own scientific research: the theories used therein and/or the methods applied and/or the concrete research results are utilised artistically. Herbert W. Franke, Vera Meyer und Markus Schrenk all serve as examples. Some of my works are also assigned to science-related art.

Constellation 2: There is no connection at all, or at least no strong connection, between the scientific and artistic practice of an individual. In the interview Karl Otto Götz as a Scientist, Rissa says “[Götz’s] scientific work had no influence on his painting.”

Constellation 3: A border crosser practices art-related science; cf. my article Vorlesungstheater.

Constellation 4: A border crosser participates in a science-art-cooperation. My Vorlesungstheater was also a cooperation of this kind.

I would now like to show that yet another constellation is possible; one that has so far remained unnoticed – namely the structural affinity between one’s own scientific and artistic practice. It is possible that there are several variants of such a structural affinity, which would then have to be examined separately. My statements, for the time being, therefore only aim to determine more precisely the variant present in my particular case.

Analysing a structural affinity

The following passage from Science-Related: Four New Series serves as a good starting point:

“Up until the end of the 1990s, I used a typewriter not only to write my own texts, but also to copy out excerpts from specialist literature I was using for my own research projects. I started out with a mechanical typewriter before switching to an electric one. Unlike the excerpts, my own texts (for seminars, lectures, talks, essays, books) were created in multiple stages; this is evident from the fact that they consist of easily recognisable layers. New sentences and paragraphs were later glued in – a procedure not uncommon at the time. Texts that emerged from complex research processes sometimes show five or more such layers; preparations for lectures presenting research results, on the other hand, usually generated no more than two to three layers.”

Quite a few scientists at that time proceeded in a similar way, which I will not expand on now. With the transition from typewriter to computer, the layers disappeared: the first version of a scientific text will be revised as many times as is necessary until the text is complete. The changes made throughout will no longer be visible in each updated version, unless coloured markings are used, e.g. to inform the reviewer which parts of the text have been revised.

Let’s take a look at the old approach: the constant cutting, pasting and layering mainly served as an editing procedure to improve the respective scientific argumentation – as well as its linguistic aspects – in order to reach a satisfactory end result. But this way of working also had an aesthetic appeal for me, which I will examine in more detail. In 1970 I transferred from the Kunstakademie Düsseldorf, where Karl Otto Götz had accepted me directly into his class, to the city’s university. I was now confronted with problems of philosophy and literary studies; more information on this can be found in Border Crosser Between Science and Visual Arts and Karl Otto Götz: Points of Contact. As well as aiming to improve my argumentation, the act of cutting and pasting, of creating several layers of text, was also connected to a certain desire – I enjoyed working like this. In retrospect, I’d say: the production of each page of a scientific text (my dissertation, an essay, my postdoctoral thesis, later a script for a lecture, etc.) contained elements of a collage, which I was already familiar with in an arts context. When working on a page, however, I never pursued artistic goals in the true sense – but I did enjoy using a collage-like process. I experienced a certain artistic fulfilment in the editing process of scientific texts. This proved that, although my artistic side may have fallen behind after transferring to the university, it never completely disappeared. I was well aware of this correlation.

A shift in artistic practice

In 1989, after a long hiatus, I took advantage of the small liberties that my scientific career (still) afforded me to resume my artistic work. This time, I took a different approach than during my art studies: I produced Schichtbilder (layered images) – a term that emerged at the time. Considering my depictions above, I will now reconstruct the general conception of the Schichtbilder, which is also applied in the new series:

- Translating and transforming the layering principle is paramount to the general artistic conception: if a page of a scientific text has been edited several times by pasting new words and sentences, the revised areas will have multiple layers of text; this is to be distinguished from re-writing an entire page from scratch. In my artistic work, this process is somewhat different: although in some cases I do also paste new elements, I usually begin by first adding a new layer that often covers the entire image. These overlays are made of, for example, dust sheets, packing paper, transparent or opaque foil. There is no equivalent to this kind of overlay when editing a page of scientific text. Hence, the artistic concept is based on expanding the layering principle; it is a free translation that opens up new creative possibilities.

- In terms of finalising a certain work, the statement “this page of the text can stay this way” becomes “this artistic work can stay this way”.

- Expanding the layering principle also enables a specific way of dealing with earlier works that may now be perceived as in need of revision: an attempt is made to revisit the work within the framework of a new series in order to reach a better solution. This can be compared to the revision of a scientific text, which is to be republished elsewhere after a few years, but whose critical reading reveals some weaknesses that are then resolved.

- In the new series, added overlays are often cut or ripped open to reveal the layer(s) beneath. Here, a principle of chance comes into play – unlike the initial production process of a scientific text. Let’s take, for instance, the overlaying of an earlier work using opaque foil. In the steps that follow, I will only know the vague whereabouts of what lies beneath the foil. I consciously refrain from taking a photo or making a drawing of the earlier work, meaning I have no visual guide when I begin to cut into the overlay: I do not know exactly which parts will be revealed. So, to a considerable extent, this is left to chance; it hasn’t been precisely calculated, but rather it simply happens this way. I deliberately bring chance into play in order to increase the degree of complexity in the creative process.

- In some cases, the new overlay is worked on further: by pasting, painting or adding a covering.

So, to summarise: the general concept of the Schichtbilder comes from extracting the collage-like process of editing scientific texts, which was used well into the 1990s, and transferring it to the arts. Thus, in 1989, the act of cutting out new words and sentences and pasting them onto the page of a scientific text (thereby creating multiple layers) evolved into an artistic work with layers that sometimes, but not always, involves cutting and pasting. And so the scientist, now returning to an artistic practice, is guided – in a semi-conscious to conscious, but not entirely unconscious way – by his own practice of producing a scientific text. The new layering principle allows for a variety of artistic approaches.

If a young person, whose life has revolved around artistic activity for a long period of time, later decides to go in a different direction outside the arts, they will likely rediscover a desire to activate their former artistic side – given that external factors work in their favour, such as having a stable career. For such an individual, reviving one’s artistic practice always also has the function of balancing the different attributes of one’s personality; pushing aside something that has long been central to one’s life will eventually cause it to resurface in a different light. This process of integrating what had once split off was, and still is, of great practical importance in my life.

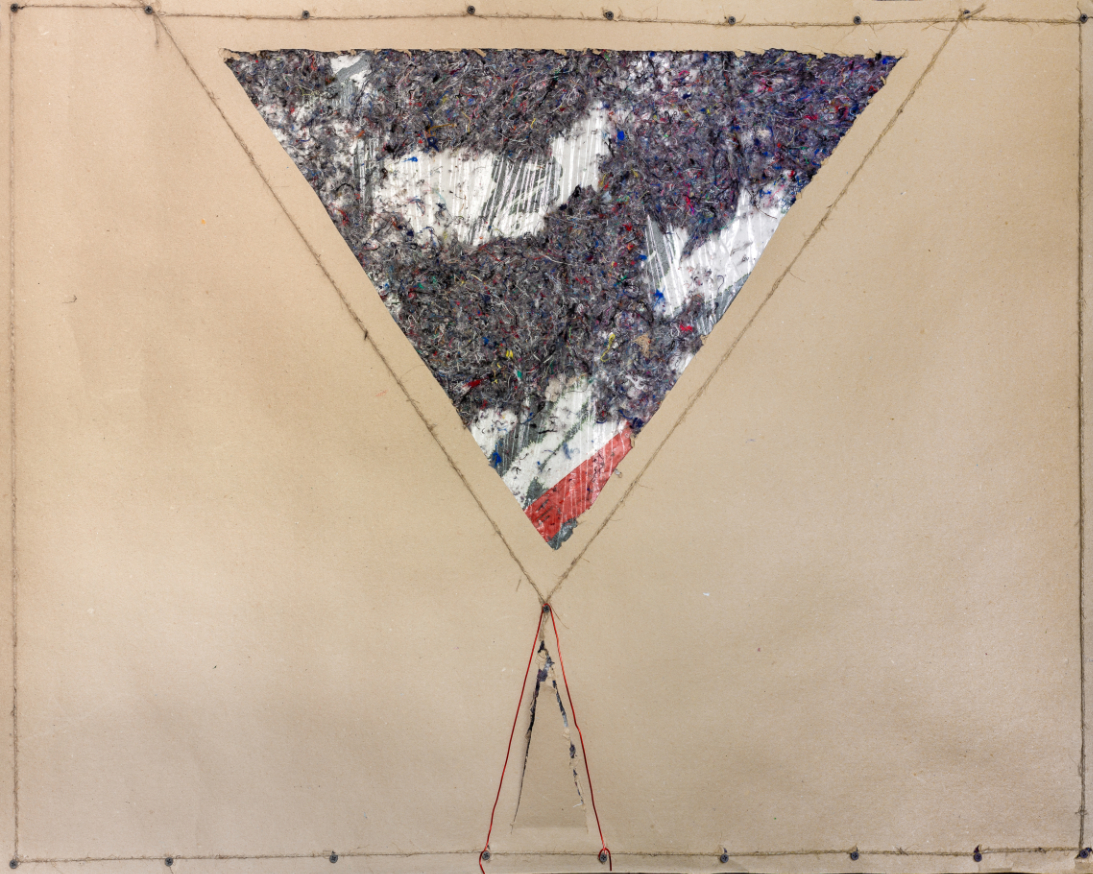

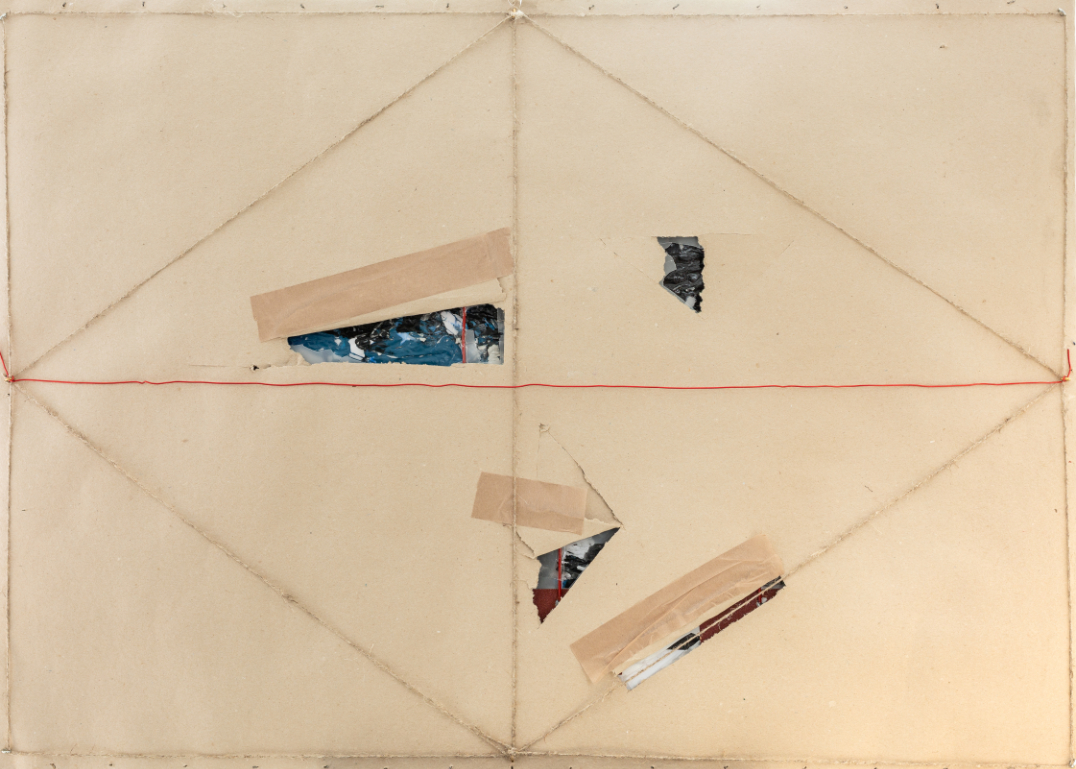

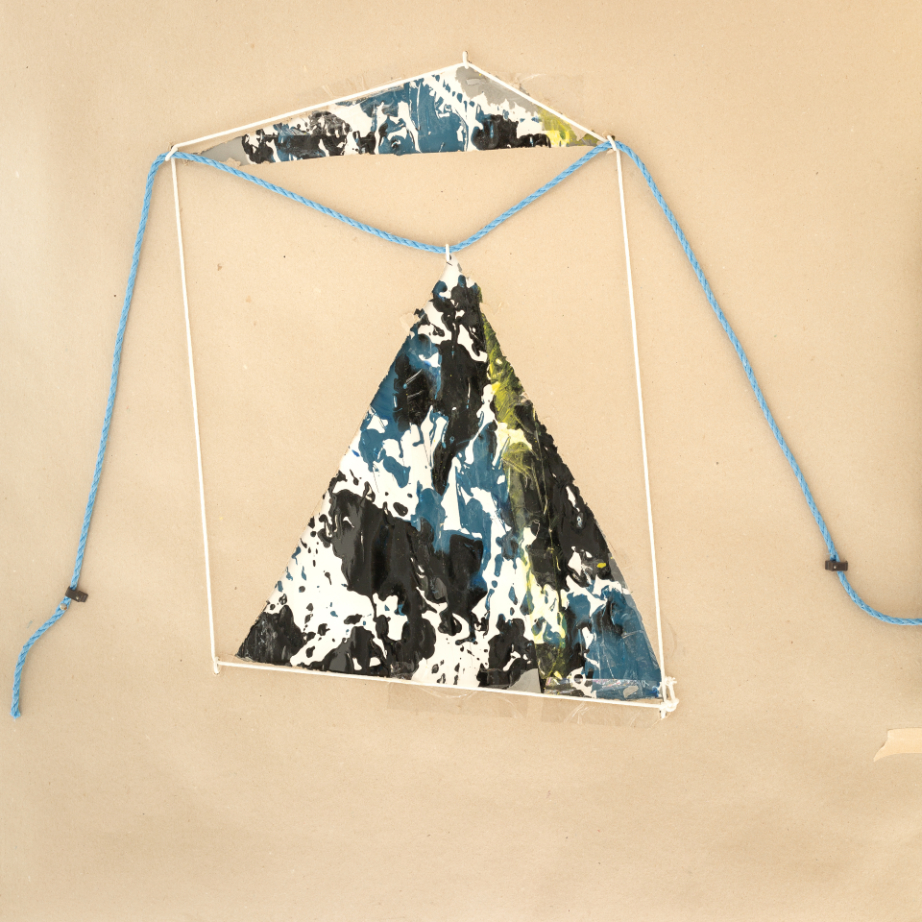

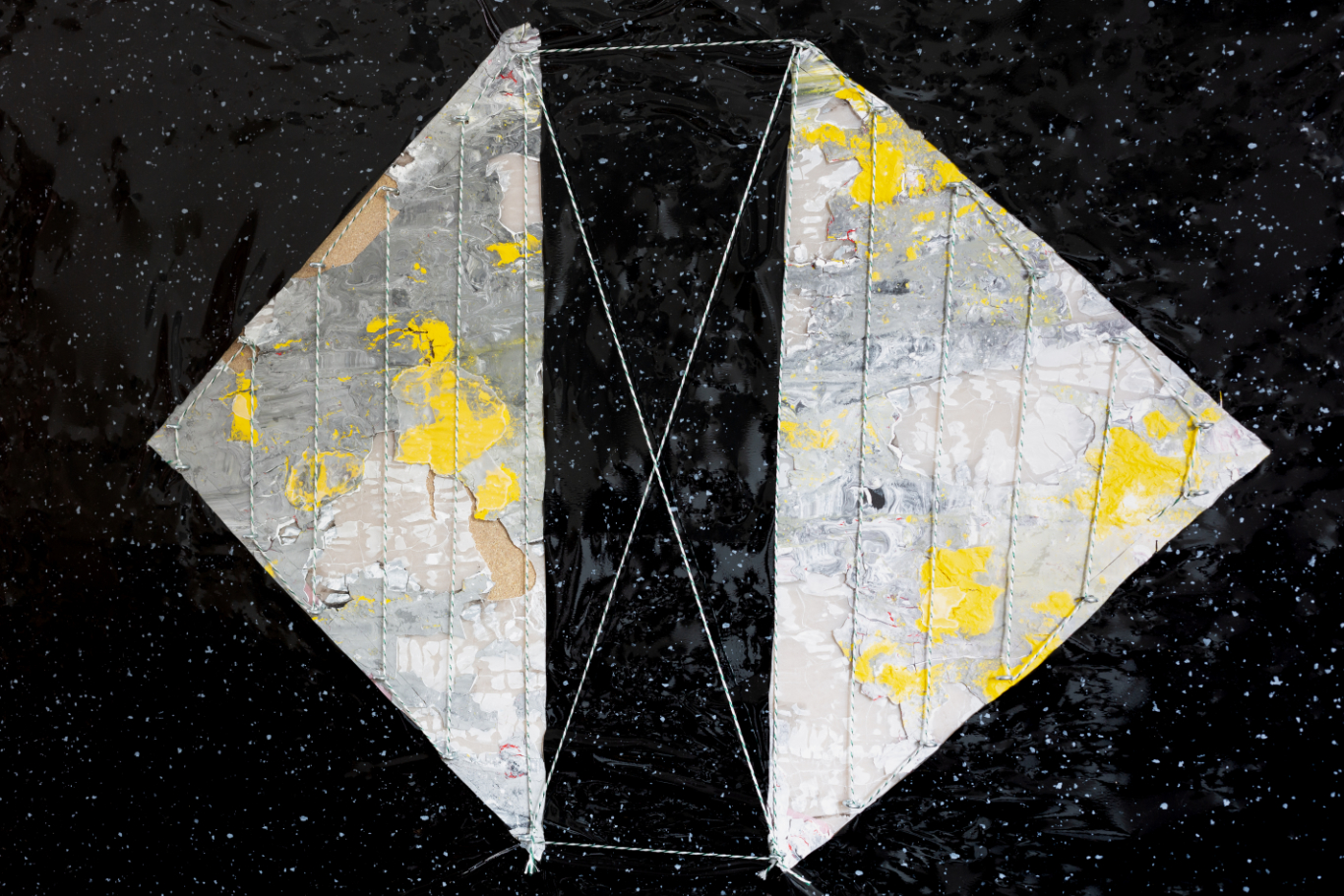

Pictured below are some examples from the series 1 and 2 created since 2020, where the layering principle finds new variations. The Packpapier-Serie (packing paper series), completed in late 2021, uses normal packing paper or heavy-duty cardboard, typically found in hardware stores, as an overlay.

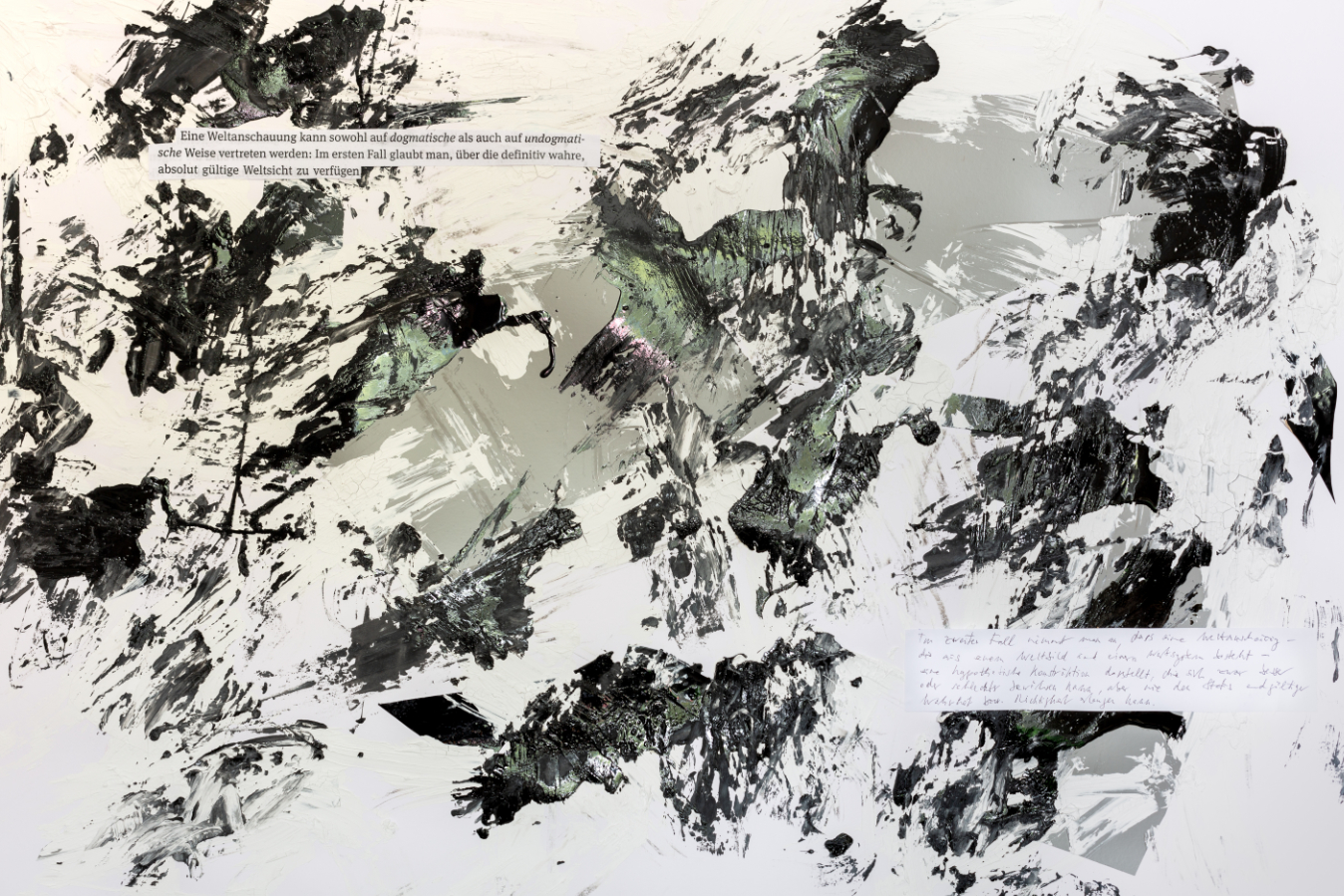

The Klebefolien-Serie (adhesive foil series) uses self-adhesive foils of various colours and patterns as an overlay. Here, I distinguish two phases:

Phase 1:

Phase 2:

2. Link to the excerpt series

In 2022, I started a third new series, which follows on from the 2019 excerpt series (then called series 4), while adding new touches. My book Ideologie (Ideology), which was published in 2012 in the series Grundthemen Philosophie (Basic Themes Philosophy) by Walter de Gruyter, further develops and systematises the concept of ideology research that I advocate (the beginnings of which date back to the 1970s). Since then, Mythos-Magazin has published many more texts on ideology research – some of them of book-length.

Ergänzungen zum Buch Ideologie 1. (Expanding on the book Ideology 1). Online: http://www.mythos-magazin.de/ideologieforschung/pt_ergaenzungen-ideologie1.pdf

Weltanschauungsanalyse – Weltanschauungskritik – Theorie des bedürfniskonformen Denkens. Ergänzungen zum Buch Ideologie 2. (Worldview Analysis – Worldview Criticism – Theory of Needs-Based Thinking. Expanding on the book Ideology 2). Online: http://www.mythos-magazin.de/ideologieforschung/pt_erg2.pdf

Fundamentalismus: Neue Wege in Analyse und Kritik. Eine Anwendung der kognitiven Ideologietheorie. (Fundamentalism: New Ways in Analysis and Criticism. An Application of Cognitive Ideology Theory). Online: http://www.mythos-magazin.de/ideologieforschung/pt_fundamentalismus-neue-wege.pdf

Auf die Schnelle. Anmerkungen zu Michael Baurmanns Text. (On the fly: Comments on Michael Baurmann’s Text). Online: http://www.mythos-magazin.de/ideologieforschung/pt_schnelle.pdf

Denkfehler. Versuch, die kognitive Psychologie mit der erkenntniskritischen Ideologieforschung ins Gespräch zu bringen. (Lapse of Thought. An attempt to bring cognitive psychology in conversation with epistemological ideology research). Online: http://www.mythos-magazin.de/ideologieforschung/pt-gt_denkfehler.pdf (zusammen mit Giovanni Tepe). http://www.mythos-magazin.de/ideologieforschung/pt_ergaenzungen-ideologie1.pdf

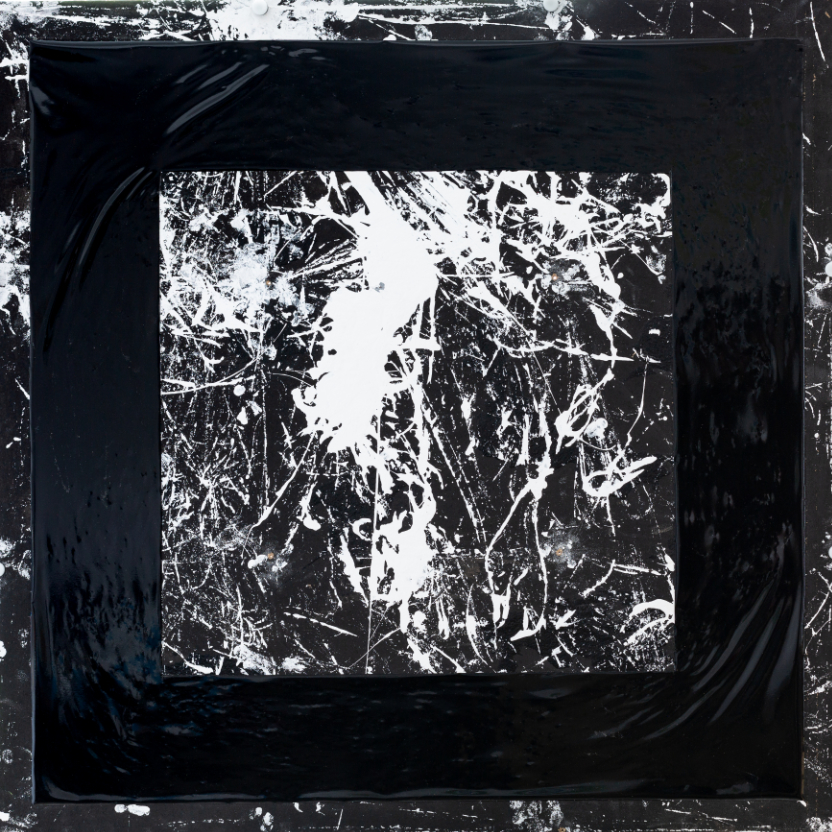

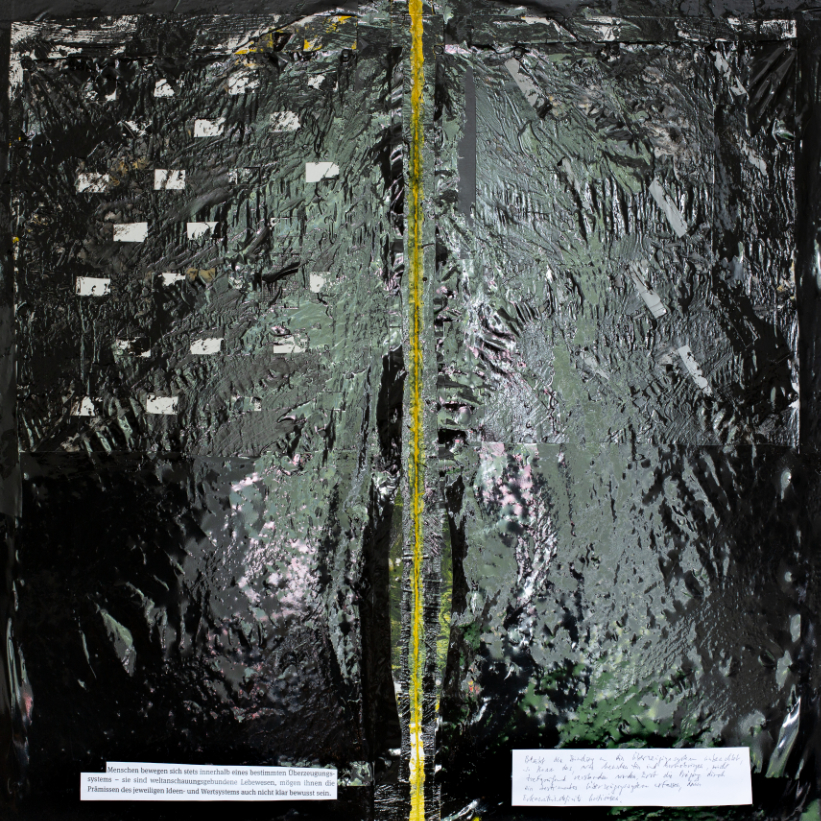

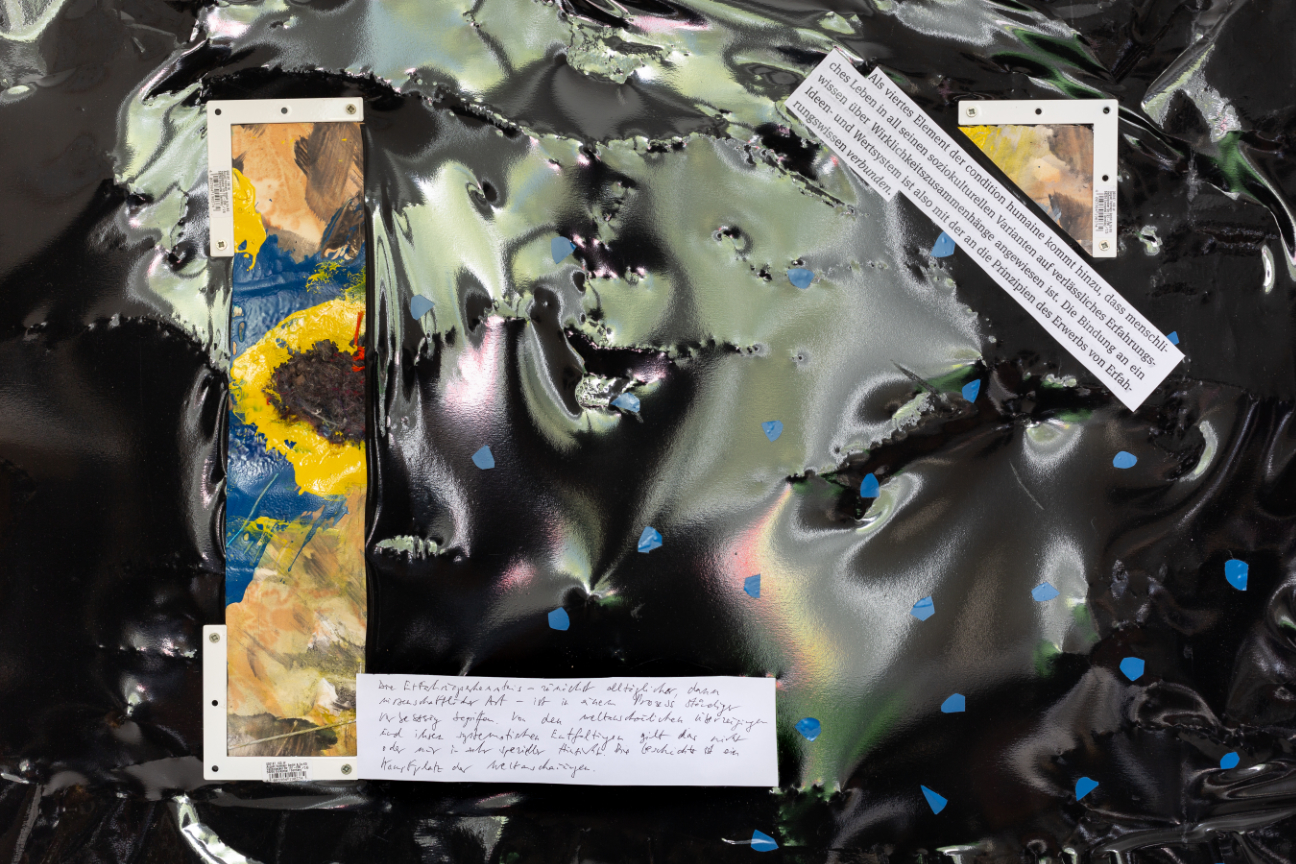

The excerpt series involved cutting and pasting elements from text excerpts dating as far back as the 1960s, to which I added a handwritten commentary borne of my current view of things. The Ideology Series, by contrast, consists of extracting individual sentences from the book Ideologie, enlarging them in a copy shop, cutting them out and pasting them onto a work from the adhesive foil series. Because I still support the theses and arguments made in the book, I don’t have to select specific sentences that still resonate with me today – unlike the subsequent revision of the typewritten pages made 20, 30, 40, 50 years ago. Instead, I can simply choose those theses and sentences that I consider to be significant, enlarge the corresponding passage, cut out the selected texts and stick them on.

Just as in the excerpt series, I added a handwritten commentary: only this time, my spontaneous and briefly formulated current viewpoint does not serve to confront a decades old text excerpt coming from an even older publication, but rather contents itself with elaborating in one way or another the selected sentences from my book, which was published in 2012.

In general, I like having my different personality attributes – i.e., the philosopher and the artist, the literary scholar (particularly the literary theorist) and the artist – encounter one another in my works. The cover image is part of the ideology series. Here are two further examples:

I distinguish here between two forms:

Form 1: Text elements are added to an image at the end (foils from a lecture, enlarged sentences from a book, etc. – sometimes accompanied by a handwritten passage). There are no intrinsic references between image and text: one personality attribute abruptly encounters the other.

Form 2: A short text is selected in advance: during the artistic process I then try to create a formal or structural correlation to the text. Form 2 will play a greater role in the near future.

Classification according to the w/k system

The three new series can be classified in terms of the w/k system developed in 5 years w/k: what happened so far. All three series can be assigned to the border crossers between science and art. The packing paper and adhesive foil series fall under the new category structural affinity between scientific and artistic practice.

The ideology series can be classified in general as science-related art, and in particular as philosophy-related art. It is also to be included in art-related science.

Further resources

The following w/k articles serve as further reading and are all available in German and English. In chronological order:

- Border Crosser Between Science and Visual Arts. Here I recount my scientific and artistic development until 2016 as well as the connections between both dimensions; the images document some of the phases of artistic work.

- The reports on the first and second w/k exhibition provide a photo series by Karsten Enderlein, also showing documentation of my exhibited artworks. In addition, the report on the first exhibition includes a video interview with me.

- The article Points of Contact, written on the occasion of the passing of Karl Otto Götz, outlines, among other things, the reasons for my transfer from the art academy to the university.

- Vorlesungstheater

- Science-Related: Four New Series

- Video Interview 1: Peter Tepe

A list of texts that expand on my art-and-science-theory can be found in 5 years w/k: what happened so far, chapter 8: Building blocks of an art-and-science-theory (only available in German).

Details of the cover photo: Peter Tepe: Ideologie Nr. 7 (2022). Photo: Mauritz Tepe.

How to cite this article

Peter Tepe (2023): Structural Affinity & philosophy-related. w/k–Between Science & Art Journal. https://doi.org/10.55597/e8642

… [Trackback]

[…] Information on that Topic: between-science-and-art.com/structural-affinity-philosophy-related/ […]

… [Trackback]

[…] Read More on to that Topic: between-science-and-art.com/structural-affinity-philosophy-related/ […]

… [Trackback]

[…] Find More here on that Topic: between-science-and-art.com/structural-affinity-philosophy-related/ […]