Text: Peter Tepe | Section: Articles about artists

On August 19th 2017, Karl Otto Götz died at the age of 103. In the time since then, many obituaries have been published, through which his artistic achievements have been widely acknowledged. It is not my intention to produce another text of that kind. I will rather try to discuss my personal contact with Götz, searching through my not-always-perfectly-reliable memory.

At high school in Osnabruck, in the middle of the 1960s, my artistic activities took many shapes. I had my representational phases, but I mostly looked up to abstract art, for example, American Abstract Expressionism or European Art Informel. Karl Otto Götz was one of the painters I admired most.

Application

Shortly before graduating from high school, I started to prepare my application for two art academies, with the help and support of my art teacher Veit Lindenmeyer. One of the main reasons Düsseldorf seemed so appealing to me at the time was that Götz was teaching there. After my graduation from high school I did not have any Plan B for my studies, and so I put all my eggs in the art basket. I was lucky: my application at the Academy of Fine Arts in Düsseldorf was accepted and I was admitted to enroll for Free Painting. This also appeased my parents who had never had anything to do with art, be it art in general, or the fine arts in particular (my father was an elementary school teacher and my mother a housewife).

Obviously, I was extremely excited to hear that my deepest hopes had come true and I had been put into Götz’ class. For me, this was a great honor and it boosted my motivation even further, already in the months before the actual beginning of the first term. At that time, the academy did not offer any common introductory classes in Free Painting yet – as a new student, you were immediately thrown into the deep end, and you had to keep your head above water among all the other students of different ages and levels. This was a big challenge.

Art Studies with Professor Götz

Right after taking up my studies in October of the eventful year of 1968, I met Götz for the first time during one of his weekly visits to our class. We talked about current events – in 1968 many of them were of a political kind –, discussed theoretical and aesthetic issues and reflected upon the latest trends in the arts, including Conceptual Art and Land Art. But mostly, we as students presented our latest works and then discussed all together the works’ strengths and weaknesses.

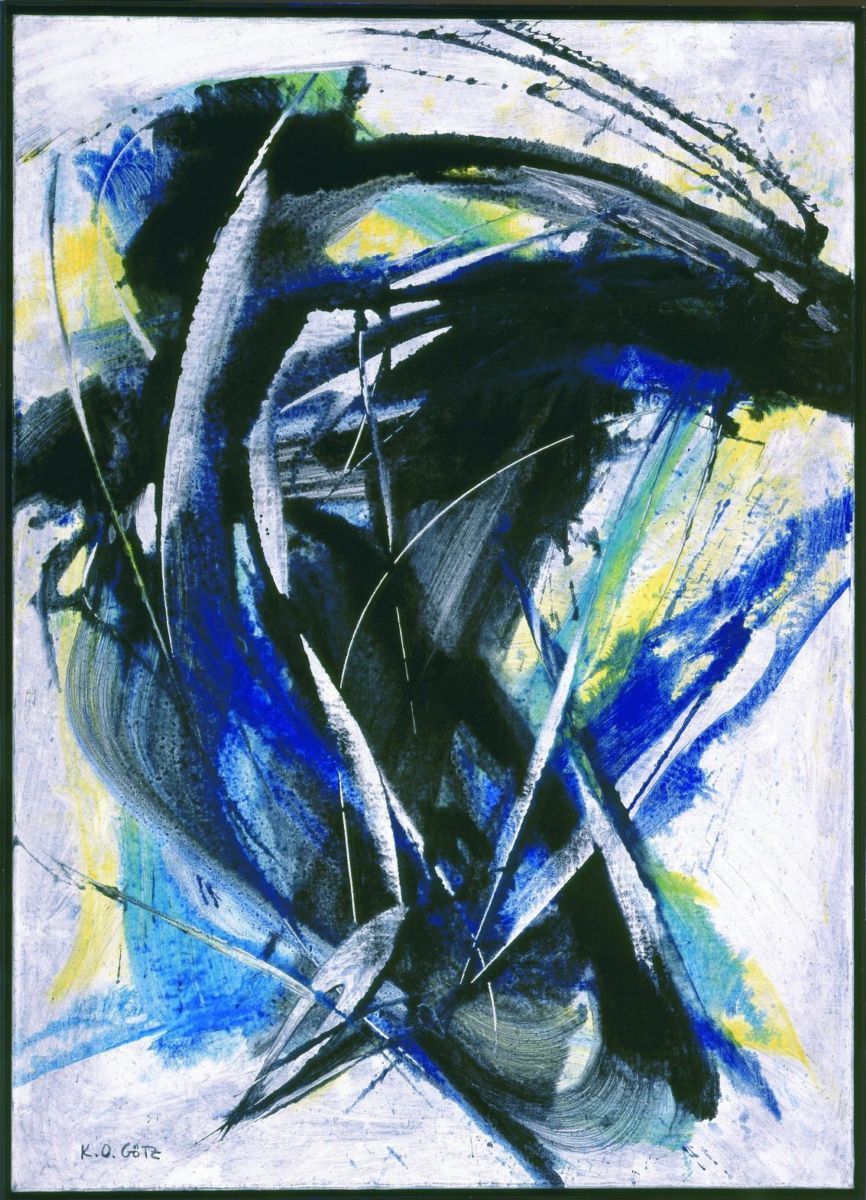

Karl Otto Götz: Torden (1969). Photograph: Olaf Bergmann.

It took me some time to understand that Götz’ philosophy was to empower his students and enable them to find their own artistic way, i.e. to invent and then implement their own, possibly original artistic concepts. He did not at all want us to imitate him, our master. This attitude also shaped his corrections and advice, which were always challenging but never devastating. He also let us carry on in ways that he considered were wrong, because he saw in the overcoming of wrong tracks the chance to later try out many different options and finally find a promising artistic concept.

As far as I remember, I was the only beginner in my class in the winter term of 1968/69. Right at our first meeting, Götz took me aside and explained to me – probably because I had asked him – how this had happened. To him, the works that I had handed in as part of my application convincingly unfolded several aspects of Abstract Art. His colleagues in the jury had found this tendency too one-sided but he had seen promising potential in it. This is why he had chosen me for his class. Götz’ decision has had a great impact on my artistic activity and I am still very grateful for it. At the same time, I now know that if Götz had not participated in the examination of the applications – for example because of an exhibit opening or an illness – I would probably never have been admitted to the course.

In the first semesters I immersed myself completely in artistic work, but I abandoned the abstract and informal tendencies of my last high school years and tried instead to experiment with new forms that were inspired by the latest tendencies in contemporary art. Götz appreciated my attempt to focus on the search for a unique artistic concept. I still remember his useful indications on how to develop the approach I had found, and I will never forget the praise he gave me when he and Gerhard Hoehme came to look at my contribution to the annual students’ exhibition.

Crisis of Direction

During my third term at the academy, I started to read more and more philosophical texts and my interest in philosophy began to preponderate over my artistic practice. Consequently, I started to attend lectures and seminars at the Faculty of Philosophy at Düsseldorf University, which was still under construction at that time. My fascination grew stronger and stronger and finally, after the fourth semester, I switched to the university where I fully immersed myself in philosophy and German literature. (More details of my biography can be found in my self-interview.)

Of course, I told my friends from the academy about this shift in priorities and my resultant crisis over my direction, but they could not quite understand why I wanted to turn away from art and many of them tried to stop me. Götz, by contrast, supported me and helped me to make my final decision. He said that if I really felt the urgent need to make this step, then I had to do it – and anyway, I could always come back to art and to his class. This reaction proved to me that Götz truly wanted his students to find their own way – even if this meant postponing the artistic work for a longer period of time.

Karl Otto Götz: Melusine (1960). Photograph: Joachim Lissmann.

In this crisis of direction in 1970, I had to make a choice among three options:

Option 1: Art continues to have top priority but I try to follow my philosophical, and slowly growing literary interests, within the bounds of possibility offered by the academy.

Option 2: I remain in Götz’ class but for a few semesters I attend university as an auditor, where I focus on philosophical and literary questions before getting back to making art.

Option 3: I switch to university for an indeterminate amount of time, but I keep in mind the opportunity Götz offered me to come back to his class after some semesters or even after some years.

Götz’ benevolent and supporting attitude helped me, after much thought, to choose option 3, which would radically change the life plan I had stuck to so far. One consequence of this decision was that I would spend my whole professional career at Heinrich-Heine University. After my late return to the arts (1989–1995 and 2013ff.) I became myself a crosser of the border between the two fields, although in a completely different way from Götz.

Götz as a Psychologist

When I was in his class, Götz was working as both an artist and a scientist. He committed himself to psychological research in order to find an exact aesthetic. In his correction sessions with us he did not in the least try to exclude this part of his work. However, he did not hold any lectures about these topics and he did not expect his students to share his enthusiasm for psychology nor tried to incite them to participate in his research. As far as I remember, he just mentioned his scientific activities casually from time to time and on these occasions, he also talked about the opposition of other artists, who could not understand why he should spent so much time on empirical research that, in their minds, did not make any sense. Many of the artists in and around the academy kept their distance from science, and this distance sometimes turned into veritable hostility. Somebody like Götz, who was a well-known painter and a scientist at the same time, was a clear exception. As far as I know, in our surroundings, there was no one else crossing the border between fine arts and science at that time.

When in 1972, Götz/Rissa published their book Probleme der Bildästhetik – Eine Einführung in die Grundlagen des anschaulichen Denkens (Questions Concerning the Aesthetics of the Image – An Introduction to Visual Thinking), in which they summarized their theoretical theses about art founded on psychology, I had already quit the academy. I heard about the publication but I read the book only years later, in preparation for the interview. It was wrong to ignore it for such a long time and I am determined to get back to it as soon as possible.

Karl Otto Götz: Batelan (1974). Photograph: Carsten Clüsserath.

Once I had begun attending university, I found it necessary for my reorientation to cut my links to the academy and thus also to Götz. Still, I continued to read articles about him and I also went to see some of his exhibitions. I would meet him again, after a very long time, at an art opening in the mid-1990s. In the meantime I had completed my PhD and my habilitation in philosophy and I worked with Herbert Anton in the German department. The focus of study and research called Mythos, Ideologie und Methoden (Myth, Ideology and Methods) that I had begun in 1987, was in full progress. Additionally, I had taken up my artistic activity again from 1989 to 1995. Götz, who remembered very well the four semesters I spent in his class before switching to university, listened carefully to everything I said, took a certain pleasure in it and asked some interesting questions.

Collaborators

After this meeting, we did not talk to each other again for many years. Our next meeting was not until 2013, when I ended my second, longer abstinence from the arts, by moving into an atelier at Werstener Kulturbunker and by creating an online platform for all those who, like me, consider themselves as border crossers between the fine arts and the sciences. This idea had come to me as early as two months before the end of my university career in December 2013. Several lecturers from Heinrich-Heine University and several from other institutions, including the academy of the arts, showed their interest in the project. In 2014, the journal’s first regular editors subscribed to the project. The concept of the online journal was then modified and enlarged because it became clear that apart from the “border crossers” between science and art there were more connections between the two fields that should also be taken into account by w/k: artists that use science in their works, collaborations between artists and scientists, the influential domain of Artistic Research and many other such topics.

In 2015, before starting to actively search for sponsors – a venture that later turned out to be disastrous – I began to drum up a great variety of cooperation partners. Of course, Götz landed on my list. I contacted his wife Rissa who fortunately gave me a positive answer. In her message from March 26th 2014 she writes: “K.O. Götz is happy that you want to include him into your project. He certainly deserves being called a border crosser, for in the 1970s he, and myself as his assistant, carried out several tests with art students and others, which were then recognized by psychological researchers in the States, Canada and England.”

In 2016, the editorial team of w/k was able to start working – thanks to the great commitment of the project’s architect Thomas Daffertshofer – to prepare the first issue, which was released online in November 2016. For this first edition, the psychologist and neuroscientist Irene Daum and I had planned an interview entitled Karl Otto Götz as a scientist, which would also take into account Rissa’s contribution to the research projects. In the spring of 2016, I contacted them again. Towards the end of our work on the interview, for which Rissa’s memories especially turned out to be essential, we visited the two in Wolfenacker on June 1st 2016 – it was very touching to meet Götz again, who by then had lost his sight.

Karl Otto Götz: Hale – Bopp III (1997). Photograph: Joachim Lissmann.

A few weeks after the release of our first round, in November 2016, the artist and w/k editor Meral Alma offered us to host the first w/k exhibition in her gallery. This gave us another opportunity to contact Götz and Rissa. The exhibition Zwischen Wissenschaft und Kunst: Düsseldorfer Akzente (Between Science and Art: Düsseldorf Accents) included contributors from our first round that had a particular relation to the city of Düsseldorf. We wanted to use a poster to hint at our interview, Karl Otto Götz as a scientist, but were very happy that Götz and Rissa generously offered to let us exhibit paintings of each of them. My last meeting with Götz took place when I went to fetch these paintings in Wolfenacker.

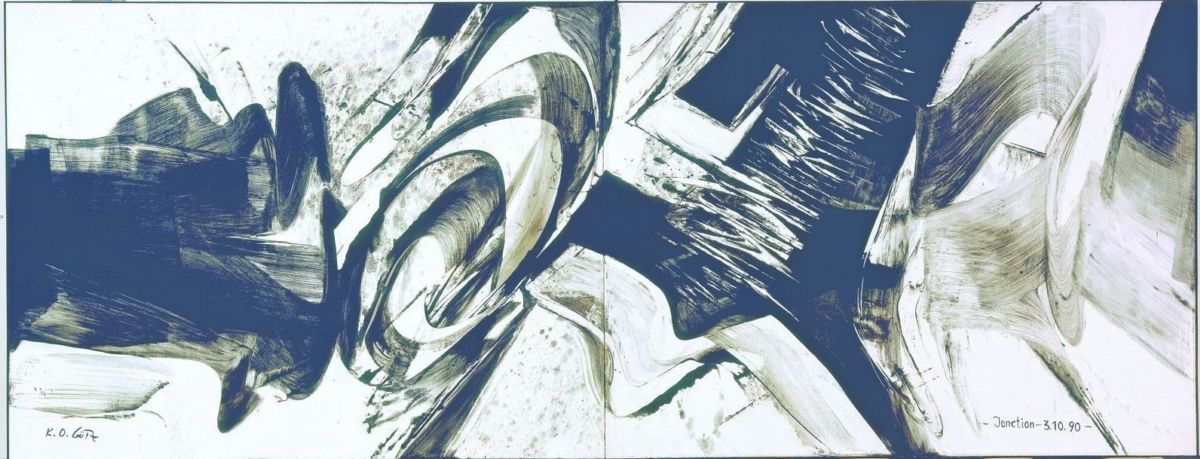

Other Important Works by Karl Otto Götz

In addition to the works already presented in this context, Rissa has provided some reproduction of further paintings she considers particularly important. The editorial board would like to thank her for her precious support. The works will be presented in chronological order. Thus showing several of Götz’ most representative works, the w/k report gives a general view of his artistic career.

![Karl Otto Götz: 24 Variationen mit einer Faktur [24 variations and an invoice] (1949) Karl Otto Götz: 24 Variationen mit einer Faktur [24 variations and an invoice] (1949)](https://between-science-and-art.com/wp-content/uploads/sites/4/2018/02/KO-Götz-Aus-24-Variationen-mit-einer-Faktur-640x480.jpg)

Karl Otto Götz: 24 Variationen mit einer Faktur [24 variations and an invoice] (1949).

Photograph: Joachim Lissmann.

Karl Otto Götz: Untitled (12/12/1952). Photograph: Joachim Lissmann.

Karl Otto Götz: Untitled (02/19/1955). Photograph: Carsten Clüsserath.

Karl Otto Götz: Giverny I (1986). Photograph: Olaf Bergmann.

Karl Otto Götz: Flagstorm (2002). Photograph: Joachim Lissmann.

Picture above article: Karl Otto Götz: Jonction 3/10/90 (1990). 200 x 520 cm, in two parts. Mixed technique on canvas. Saarland Museum Saarbrücken, on loan from the K.O. Götz und Rissa-Stiftung. Photograph: Carsten Clüsserath.

How to cite this article

Peter Tepe (2018): Karl Otto Götz: Points of Contact. w/k–Between Science & Art Journal. https://doi.org/10.55597/e2519

Be First to Comment