Text: Mirjam Hildbrand and Anna-Sophie Jürgens | Special Contributions

Abstract: This article examines the position of circus within the arts and sciences by exploring the interest of early 20th-century artists in circus phenomena – as a source of inspiration for artistic projects and studies – and the location of circus as an object of research within the panorama of scholarly disciplines. As the speakers – experts from different academic fields, curators and circus practitioners – at the second symposium on Circus and the Avant-Gardes (May 2020, University of Bern) examined, (studying) circus and avant-garde connections contributes to a better understanding of the artistic movements from the early 20th century and their cultural legacy, the history of popular entertainment and the cultural relevance of circus arts today. It also clarifies the importance of circus as an object of interdisciplinary and artistic research.

Note: Articles exploring the interfaces between science and art in the field of Circus & Science are highlighted by a pink frame.

***

For historical avant-garde artists, circus was a treasure trove and a creative goldmine for ideas about the reformation of existing artistic practices and the art of the future. What exactly this looked like and what forms it took was the subject of an online conference hosted by the Institute of Theatre Studies at University of Bern in May 2020, which brought together an array of scholars from academic disciplines as diverse as Theatre and Circus Studies, Performing Arts, History, Literary and Cultural Studies, Gender Studies and Artistic Research, as well as curators, circus practitioners and facilitators of international circus events. Participants of the virtual conference were circus artists who are academically engaged and circus-related scholars exploring circus at the intersections between artistic expression and academic and artistic research. Their discussions and discoveries are interesting for the online journal w/k which focuses on the interfaces between science and art. The title refers to the German language terms ‘Wissenschaft’ (science) and ‘Kunst’ (art). Usually ‘Wissenschaft’ is translated as ‘science’, although the German term is much broader and includes every systematic knowledge producing enterprise and research activity, and thus also, for instance, the Humanities (for more details see here).

This article is the companion piece to Circus Arts and the Avant-Gardes, which illuminates the richness and multidimensionality of the circus’ cultural capital within the context of the historical avant-gardes and their contemporary reinterpretations. While that first discussion of the circus-avant-garde theme set the scene by providing contextual background, this piece contributes a closer focus to exploring the position of circus within the arts and sciences. It examines the interest of early 20th-century artists in circus phenomena as a source of inspiration for both artistic projects and studies, and the location of circus as an object of research within the panorama of scholarly disciplines, particularly in the Humanities and the field of Artistic Research. In so doing, this article serves as introduction and contextualisation of circus and the new ‘Circus & Science’ section.

Point of departure: Circus, a fountain of youth for the arts at the beginning of the 20th century

At the beginning of the 20th century, avant-garde artists – including Futurists and Dadaists, Bauhaus protagonists and Russian theatre reformers – discovered the circus and its aesthetics as a treasure trove and creative goldmine, both for ideas about the recasting of existing artistic practices and the art of the future. Regardless of whether they hailed from Russia, Germany or France (or, indeed, from many other countries), avant-garde artists drew inspiration from the circus’ depiction and exploration of performing bodies and body techniques, its anti-Aristotelian dramaturgy (successive acts whose content was only loosely connected, except in circus pantomimes), and its entertaining, non-conventional protagonists who questioned the prevalent realist and naturalist – or simply conventionalist – views of art. The experimental, unorthodox and radical projects of avant-garde innovators also drew from the circus’ concept of space, which allowed and forced interaction with and among the audience. They also expanded on the circus’ strategy of playing for and with a heterogeneous community. As theatre and media scholar Ekaterina Trachsel highlighted at the virtual conference Circus and the Avant-Gardes, non-narrative circus programmes inspired avant-garde artists – above all film maker Sergei Eisenstein – to reconsider causality, integrity and identity in their works. New, highly-influential artistic concepts and methods – such as the method of montage – were the result. Avant-garde artists also cultivated fantasies around and about circus. Removed from institutional live circus, separated from their role in the circus arena and their performance routines, and reinterpreted in different, interrelated media, circus phenomena overlaid with representations of an idea of the circus generate the imaginary of the circus.[1] Avant-gardes artists explored such circus imaginaries by promoting the idea that everyone, not only circus performers, can rise above themselves, and that circus goes beyond reason. Celebrating the circus’ ‘immediacy’ and ‘difference’ from everyday life, and its enchanting power to bring very diverse people together, theatre makers and painters of the early 20th century often nurtured and transported ideas of circus imaginary that were only loosely linked to circus reality.

Czech avant-garde artists, for example, knew and visited Circus Medrano in Paris. However, as Cultural Studies scholar Anne Hultsch (University of Vienna) suggested in her presentation, besides attending circuses abroad, they had little opportunity to see real circus performances because there was no permanent circus building in Prague and travelling circuses rarely strayed into the capital. Interestingly, Czech avant-garde artists nevertheless drew inspiration from the circus and took up its aesthetics: by referring to its cultural ‘imaginary’. A description of Seurat’s famous circus painting (1890/91) by Artuš Černík may serve as an example, in which he assumes something about what traveling shows were like. Černík expresses nostalgia for travelling shows and mourns their absence in everyday life.[2] As a ‘remedy’ artists flocked to variety and other forms of popular theatre and entertainment that were more accessible – and soon replaced circus references in the works of Czech artists. In the transition to other entertainment avenues they started to pull from a variety of different sources beyond circus, Czech avant-garde artist and theorist Karel Teige thus wrote in 1922 (in a text about New Proletarian Art) that art should learn and draw from art forms that people understand and that captivate them: Indian tales, stories by Buffalo Bill, American series in the cinema or grotesque Chaplinades, jugglers from the popular stage, travelling singers and circus clowns, among others.[3] The avant-gardes’ interest in circus dwindled, it seems, and disappeared from their theoretical aspirations once they had their own theatre stages and were thus able to create their own performance practice.

Artists studying (in) circus

As pointed out by Theatre Studies scholar Laurette Burgholzer (University of Bern), French avant-garde artists and theatre innovators – in contrast to Czech cultural reformers – did not only attend performances of Paris Cirque Medrano (and were particularly inspired by its clowns), but also studied circus techniques systematically and used them for their own projects. French theatre director, actor and dramatist Jacques Copeau (1879–1949), who founded the famous Théâtre du Vieux-Colombier in Paris, collaborated with French clown troupe Fratellini. Copeau perceived them as innovators with a unique understanding of the body and understood clowning not as a result but as a means and method for the training of theatre actors. Like many of his contemporary stage reformers, he saw the traditional theatre style as an obstacle to genuine artistic creation and wanted to free the theatre from being obscured by texts in order to create the ‘new’ actor of the future. French director and actor Charles Dullin (1885–1949), founder of the Atelier theatre and drama school in Paris, staged Voulez-vous jouer avec moâ? written by Marcel Achard in 1923, a play inspired by circus aesthetics and clown characters, in collaboration with Albert Fratellini as an advisor. The French pantomime Jules-Maurice Chevalier alias Farina (1883–1943), on the other hand, performed on stage with the famous professional clown Chocolat fils at the Théâtre de l’Exposition des Arts Décoratifs and tried to systematically redefine and revalue the art of pantomime in order to enshrine it in the Pantheon of Arts. Striving for a reformation of the circus pantomime by means of literature, he gave a lecture in the circus Medrano about historical connections between mime and circus, and proposed a redefinition of the circus pantomime with the help of cerebral clowns (‘clowns cérébraux’). Cerebral clowns are what Farina called intellectuals (particularly writers), interested in circus, who (according to the mime) should write the storylines of the circus pantomimes of the future. The expression ‘clown cérébral’ was originally used by a journalist to describe the French poet, playwright, filmmaker and visual artist Jean Cocteau (known as one of the most influential avant-garde filmmakers) and his play Boeuf sur le toit [Ox on the Roof], a ballet farce featuring professional clowns – the Fratellinis among them. Farina’s ideas were picked up by the Fratellinis who used them to add a narrative layer to the plot and structure of their acts, and in so doing also reinforced and reinstalled the presence and artistic appeal of the Pierrot figure, which once was particularly popular in French theatrical pantomime (of the early 19th century).

Circus and the Avant-Gardes today: Artistic Research in Circus Arts

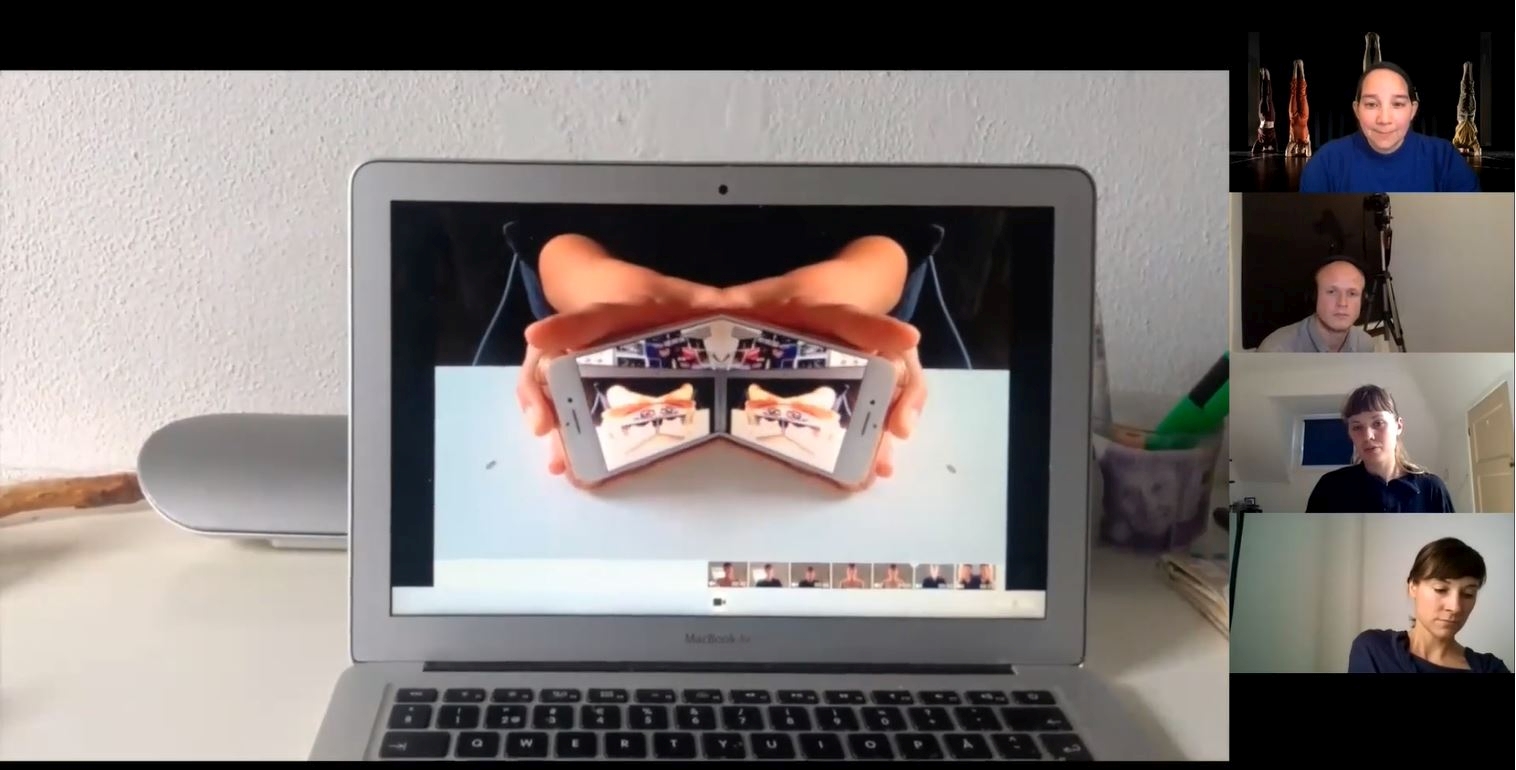

According to the UNESCO definition, every creative systematic activity with the goal of expanding knowledge can be called research. But what is creative, and whose status and knowledge is being negotiated in ‘research’? Art and research amalgamating projects in the still-emerging field of Artistic Research explore this and other questions, such as: How does art do research with its own means? What knowledge is produced in art, and does it have specific qualities (being felt, tactile, etc.)?[4] Avant-gardists, for instance at the Bauhaus, used and transferred scientific methods into artistic processes in their experimental aesthetics which are rediscovered and reinterpreted in the field of Artistic Research; an approach that is also reflected and developed by contemporary circus artists. At the symposium Circus and the Avant-Gardes, the directing duo Cox Ahlers and Jenny Patschovsky presented their collaboration with the Bauhaus Dessau Foundation. The two contemporary circus artists have been staging cross-genre and site-specific performances at the Bauhaus festivals since 2016. They were invited by Burghard Duhm, a curator of the stage programme at Bauhaus Dessau, who was also present at the virtual conference with a contribution on the early Bauhaus artists and their connections to circus. Based on the Bauhaus spirit and exercises, for the symposium Circus and the Avant-Gardes they explored the body as material and the object as partner. In this virtual space, they did this with their pre-recorded video as well as in their live performance for, and with, all the participants via Zoom, thus further developing visions of the Bauhaus artists Oskar Schlemmer, Josef Albers and László Moholy-Nagy. In collaboration with the circus artists Marie-Andrée Robitaille, Kolja Huneck and Carina Klingsell, they examined the impulses that space, geographical distance and architecture may provide for both scholarly discussion and for reflecting on how we react to the world that surrounds us. They also suggested raising awareness of how the material interacts with the artists (and with ourselves).

Additional information on the picture byhouse! by Carina Klingsell: Contemporary circus and Bauhaus – A zoom into the site-specific research by Jenny Patschovsky and Cox Ahlers in Collaboration with Marie Andree Robitaille, Carina Klingsell and Kolja Huneck, May 2020.

Projects of this kind investigate circus beyond its function as an entertainment or spectacle. They explore new frameworks for knowledge to be acquired in different modes in circus arts. Another example thereof was presented by dramaturge Anna Wagner and Theatre Studies scholar Eike Wittrock (University of Music and Dramatic Arts Graz) in their curatorial reflection exploring the intersections between circus practice and theory, art and research. They discussed circus as a starting point for contemporary scholarly theory and as a looking glass for present (and future) artistic work. They introduced their polarising thesis that the contemporary, independent performance scene – with its pluralism of forms and contents – was created in relation to 1970s circus revival. Wagner and Wittrock go on to explain that in its process of professionalisation, the circus was excluded from the contemporary aesthetics. The premise of a contemporary performance circus – created by Wagner and Wittrock with the project called The Greatest Show on Earth premiered at Kampnagel in Hamburg in 2016 – thus provided a challenge for contemporary artists, curators, circus scholars and audiences alike to rethink performance, production and perception economies and circus theory.

The circus artist Roxana Küwen, a graduate from Fontys Academy for Circus and Performance Art (Tilburg, Netherlands), specialised in static trapeze and foot juggling. She explored a different approach to Artistic Research in Circus Arts and circus practice at the symposium on Circus and the Avant-Gardes. Roxana Küwen is a border crosser: on the one hand she works as a circus artist, on the other hand she works with researchers. As a member of the project group CiNS (Circus in National Socialism) – together with historians, circus and theatre educators as well as political activists – she develops research-based artistic outreach programmes (travelling expositions and multidisciplinary performances) to investigate and inform about the history of circus during National Socialism in Germany, including stories of persecuted and murdered circus artists. In her collaborative work, which also includes exchange and cooperation with contemporary witnesses and their families, the project CiNS combines lectures, reading, acting, circus arts and live music around fragments of the life of Jewish circus artist Irene Bento, who survived the Holocaust by hiding amongst the German circus company of Circus Adolf Althoff. Through artistic tools of abstraction Küwen’s performances invite the audience to experience empathy and emotional involvement linked to history and historical knowledge on an individual level. The aim of the project is to raise awareness in academic, pedagogical and artistic contexts about a blind spot in circus history, in order to contribute to a culture of remembrance related to the present time.

Artistic Research in Circus Arts, linked to historical Avant-Gardes, is also the field explored in the work of the duo Künkel and Hildbrand. Since 2018, För Künkel (a Berlin-based scenographer) and Mirjam Hildbrand (dramaturge, theatre scholar and co-organiser of the two symposiums on Circus and the Avant-Gardes) explore the intersections of contemporary artistic practice and academic research on circus arts in Berlin around 1900. They use creative and multidisciplinary artistic research methods such as collecting and (re)arranging, and mapping or embodiment as a technique of mediation between body-based and theoretical knowledge. With these methods, they are creating a dialogue between historical and contemporary performing practice, and thus between contemporary artists and performance tradition. As academic and artistic investigation of circus arts in the German context is still emerging (very late, in contrast to other countries where Circus Studies are already institutionalised), dialogue as a theoretical and practical framework for knowledge acquisition and transmission turned out to be an important research method and result. Such dialogues include the Circus Archive Winkler but also the Swiss performer and circus director Ueli Hirzel, whose career and avant-gardist project Cirque O was recently discussed by Mirjam Hildbrand in an interview – using methods of oral history to create an artistic podcast.

Thus, discussing circus at the intersection between art and science does not only contribute to a better understanding of the artistic movements from the early 20th century and their cultural legacy ever since, but also clarifies the importance of circus as an object of interdisciplinary and Artistic Research.

The virtual symposium Circus and the Avant-Gardes included presentations by Dr Birgit Peter (University of Vienna), Dr Dr Anne Hultsch (University of Vienna), Roxana Küwen (Project CiNS), Burghard Duhm (Bauhaus Dessau), Dr Katalin Teller (Eötvös Loránd University Budapest), Dr Laurette Burgholzer (University of Bern), M.A. Ekaterina Trachsel (University of Hildesheim), Anna Wagner (Künstlerhaus Mousonturm) & Dr Eike Wittrock (University of Music and Performing Arts Graz), M.A. Jenny Patschovsky and Cox Ahlers (Contemporary circus artists) and MA Mirjam Hildbrand (University of Bern) & Dr Anna-Sophie Jürgens (Australian National University).

The symposium was supported by the Fund for the Promotion of Young Researchers of the University of Bern. The event was part of a collaboration with the Freie Universität Berlin (FU). An initial symposium on Circus and the Avant-Gardes was hosted by the EXC 2020 Temporal Communities at the FU in March 2020. It was funded by the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (DFG, German Research Foundation) under Germany ́s Excellence Strategy in the context of the Cluster of Excellence Temporal Communities: Doing Literature in a Global Perspective – EXC 2020 – Project ID 3900608380.

Picture above the text: Conference poster (2020). Photo: Mirjam Hildbrand.

Follow our circus and avant-garde adventures on Twitter: #circus_avantgardes and #circusandscience

[1] See Peta Tait, Circus Bodies: Cultural identity in aerial performance, New York: Routledge 2005, 123.

[2] Artuš Černík, ‘Radosti elektrického století’, Sborník Devětsil 1922, 136–142 (138, 140).

[3] Karel Teige, ‘Nové umění proletářské – Úvodní článek’, Sborník Devětsil 1922, 5–18 (16).

[4] For a short introduction to Artistic Research, in German, see LaborARTorium online (for a reference for the UNESCO definition, see ‘Leseprobe’ page 10).

How to cite this article

Mirjam Hildbrand and Anna-Sophie Jürgens (2020): Circus & the Avant-Gardes: Between Science and Art. w/k–Between Science & Art Journal. https://doi.org/10.55597/e6091