A conversation with Anna-Sophie Jürgens | Section: Interviews | Series: Street Art, Science and Engagement

Abstract: James Houlcroft, also known as Houl, is a street artist and teacher whose public art investigates our relationship with nature and environmental knowledge. His clever and witty artworks can be found in streetscapes, galleries and festivals. In this article, James reflects on the knowledge-oriented, educational and inspirational role of street art – street art as public pedagogy – in the various media and formats he explores in the Australian capital and beyond.

James Houlcroft (aka Houl), it is a great pleasure to welcome you to our online journal w/k! You are an incredibly prolific and versatile artist who has been described as “an educator” – with a love for teaching and art – who “incorporates art into his classroom, and his classroom into his art“ (Gilliam 2019). You are a secondary school teacher and a street artist. As a street artist you work with a variety of materials – including spray paint, cardboard creations and public surfaces. Your art not only adds wit and humour to streetscapes, but can also be found in galleries and is a regular part of festivals; for example, at a recent Enlighten Festival in Canberra, your art was projected onto the façades of the National Science and Technology Centre (Questacon) and the National Library of Australia. Many of the characters in your public art are animals, which you also put into an educational context on your Instagram page – you explain how endangered they are, for example, or how they are represented in pop culture. All of this is extremely interesting for w/k, and in this article we would like to invite you to share your thoughts on your relationship with nature and environmental concerns, as well as the educational role of public art, with the aim of better understanding the power of street art to communicate knowledge and, in particular, environmental messages and awareness.

Hi. Great to be here.

Environmental communication and Street Art – as public education?

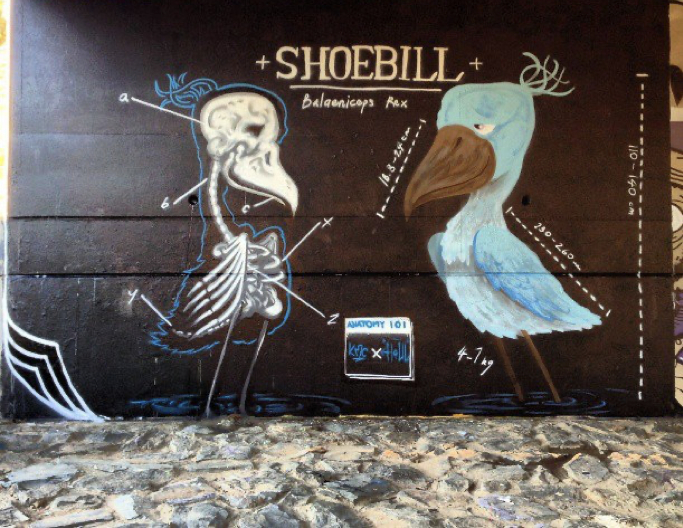

James, some of your artworks show critically endangered species, for example a Chinese Giant Salamander, which you highlight in your image descriptions. Other artworks explain things like the anatomy of a shoebill. What are your thoughts on the educational role of street art? Do you think of street art as a form of pedagogy?

I think it’s dangerous not to think of street art as pedagogy. As street art becomes increasingly embraced by the wider public, its power to communicate ideas and understanding grows too. Art is about the communication of ideas from artist to audience; street art, more than any other form of art, reduces the gap between the two, bringing artworks to the public, whether they want it or not. So to ignore its educational potential shows an inherent misunderstanding of the purpose and role of art as a whole.

Why do you think it is important to bring environmental knowledge or awareness and street art together? Why does it matter to use street art as a means of environmental communication?

A lot of street art is context-based works created for a particular location or to be viewed from a particular angle. In this way, street art is inherently connected to the environment within which it exists so an understanding of that environment can only work to augment the art. Extending this to an understanding of the wider environment, it reminds the audience that their city or town is (in)directly part of something larger.

I often use endangered – and, where possible, locally native – animals as the subject of my artworks, to juxtapose the fragility of these animals’ existence with the urban sprawl where street art is so often found. It’s also just a prettier topic. People are so dull compared to the golden lines of a Southern Corroboree Frog, arrowed plumage of the Regent Honey Eater or the shiny carapace of the Lord Howe Island Stick Insect.

Public Art and Learning

Art appeals to the affective domain of learning: it elicits visceral, emotional responses and engages the imagination (see Bengtsen 2018, 13). To what extent do you consider street art to be a vehicle for learning? How does street art enable a deeper understanding of environmental issues?

Street Art, when exploring environmental issues, or any societal concern, is effective at presenting understanding in an easily consumable package. The bright, bold nature of the medium creates a more intrinsic appreciation of the issue, and gives the issue a visual component, a face, something you can’t ignore when it’s painted on the wall you pass on the way to work each morning. The educational angle, the deep understanding, is hidden behind the fans of colourful spray paint and brush strokes, but it’s still there. I mean, or it could just be a picture of a dog dressed as a bikie. They don’t all need to be deep and meaningful …

Street art is an urban art practice that encompasses a range of techniques and materials. You said in an interview that you moved from stickers to spray paint. However, you do not only create aerosol murals – e.g. as part of Canberra‘s recent Street Art Festival – you also work on street signs and canvases, cardboard, cellophane foil, video cassettes and mobile objects (such as skateboards). What role do the different mediums play in developing or presenting the message of your creations/artwork?

The medium of the artwork definitely dictates the amount of narrative or message that can be portrayed. Murals are more adept at storytelling where the size of the artwork means you can fit more in with those small details blown up big for all to see.

The ongoing body of work, #cardboardandcableties, features artwork on found cardboard that I leave around the place for people to collect and take home for themselves. While retaining some of the storytelling potential of murals, this generally moves more towards portraiture of the animals I choose. No wider narrative; more a snapshot of the animal. I write on the back as well, often including their Latin name, their conservation status and a brief piece of information about the animal to drive home the educational angle to it. The interesting thing with this is that ultimately only the person who finds the artwork sees the info on the back, so it’s a very small teaching moment.

Finally, while not necessarily within the scientific realm, the pen and ink series I’ve been working on since 2017, in which I create a new cover illustration for each book I read, is an extension of my role as an English teacher. I use this to not only reflect on the book after I’ve read it, but also to share the books I read for those who are interested. This originated as a monthly art project started by Alexis Winter in 2016, and I just adapted it and continued it after the initial 12 months finished. It’s helped me be more aware of the books I read and the imagery and messages within.

How has your engagement with environmental and science themes developed? What artistic results have these explorations led to?

While I’ve always been fascinated by the natural world – growing up in a small riverside community surrounded by the bush – and passively explored this through my artworks, it wasn’t until I was invited to take part in the first series of Co-Lab, a project run by Lee Constable,* that I began to more actively, pointedly and directly explore environmental and science themes. It was no longer about just choosing a weird animal to paint, but getting an understanding of the unique elements to the subject before painting it. I think this ongoing engagement with environmental and science themes has given my work more purpose and drive, where it’s no longer art for art’s sake. I mean, it still is sometimes, but when I want to engage in that scientific angle, it’s definitely more careful and considered.

The artworks I created for the collaborations with these scientists, both through Co-Lab as well as Shirty Science, have been some of my most memorable artistic experiences, and I relish the opportunity to work alongside people who have such passion and dedication for their field, and bring this to the public with my artwork.

To that point, if you’re a scientist or researcher reading this, and you have a rad project you’re working on, please hit me up. I’d love to try and draw it.

Artistic Street Art Strategies: Wit and Recycled Material

James, I think that many of your artworks are not only highly imaginative but also have a cleverly humorous, amusingly illuminating dimension that could be captured by the concept of wit. “[W]it is comprised of surprise”, a colleague of mine wrote recently, “the sudden provision of an unexpected creative insight via a novel quip or image” (Svelte 2022). What do you think about this? Do you see wit as an artistic strategy in your work and if so, how is it particularly productive in getting your messages across?

To be honest, any (intentional) wit that I include is very self-indulgent and predominantly contained within the captions I include on my Instagram posts, where I really just try to write something that I’d want to read. These dance between silly anecdotes, made-up conversations or dumb facts that I find amusing. Sometimes these stimulate interest in the post, but I mostly assume people skip over the comments altogether, making me go even stranger in the next post because if people aren’t reading them, why worry about making it too serious.

What other strategies would you consider characteristic of HoulArt, especially in the context of our interest in environmental themes and art (looking at works like Mushrooms on Gladwrap for example)?

I think if anything was truly characteristic of me and my artwork, I’d want it to be my use of cardboard, always scrounged and recycled, which I paint on and leave out in the public for people to find and take home. This started as me exploring different ways to deliver art to the public, where I’d attach artworks on cardboard where traffic tended to back up, but where people wouldn’t necessarily walk. However, when I realised that people were finding them and taking them down to keep, I discovered I much preferred to give work away to those who really want it, and have the energy to search for these small pieces, so embraced this. This further removed the boundary between artist and audience that street art has already begun to break down.

The GladWrap pieces were born out of necessity, where I was seeking walls that were further out of the public eye, so I borrowed what a Canberra artist called Walrus had been doing years prior, and made my own walls with GladWrap. This allowed me to experiment with the environment a little more in the works, situating the design within the landscape as opposed to sitting on top of it. Ultimately, the GladWrap came down too quickly, and often by the time I returned to collect the rubbish, it had scattered too far and wide, so I stopped it to avoid littering and damaging these areas more than had already been done.

If you could invent a science, what would it be?

Fictochromatology – the study of impossible colours, those that exist outside the visible spectrum of human colour perception.

Lactoartemology – the study of cheese as an artistic medium. Shout out all my lactose intolerant cheese eaters out there. It’s killing us slowly but deliciously.

James, thank you for this fantastic conversation!

*See Lee Constable: Founding “Science Meets Street Art” Co-Labs recently published in w/k.

References

Bengtsen, Peter (2018): Street Art and the Environment. Almendros de Granada Press.

Houl’s Instagram page at @houlart.

Gilliam, Darin (2019): Meet Annapolis’ Newest Artist: James Houlcroft. Online: https://www.visitannapolis.org/blog/stories/post/meet-annapolis-newest-artist-james-houlcroft/ (accessed on 18.4.23).

The Street Art Curator (2012): Australian Street Artist: HOUL. Online: https://thestreetartcurator.wordpress.com/2012/08/18/australian-street-artist-houl/ (accessed on 18.4.23).

Details of the cover photo: James Houlcroft: Sunset Remora (2017). Photo: James Houlcroft.

How to cite this article

James Houlcroft and Anna-Sophie Jürgens (2023): HoulArt: Wit and Public Inspiration. w/k–Between Science & Art Journal. https://doi.org/10.55597/e8822

Be First to Comment