A conversation with Anna-Sophie Jürgens and Blake Thompson | Section: Interviews

Series: Street Art, Science and Engagement

Abstract: In this article Australian science communicator Lee Constable discusses her work at the intersection between street art and science. Lee is the founder and lead of four science-street art collaborations: the Co-Lab: Science Meets Street Art (Canberra 2015, 2016, 2017) and Visualising AI – Science Meets Street Art (Brisbane 2022). The article explores her thoughts on the power of street art for communicating science, its societal role and relevance, and the (artistic) outcomes the Co-Labs have led to.

Lee, it is a great delight to welcome you to our online journal w/k! In 2018, the Australian National University (ANU), your alma mater, wrote about you: “Lee Constable is passionate about mixing science with media and the arts.” Unsurprisingly, you received multiple degrees from the ANU: a Bachelor of Arts, a Bachelor of Science (Honours) and a Master of Science Communication Outreach with the Questacon Science Circus (Questacon is the Australian National Science and Technology Centre). Since then, you have worked as a science communicator, TV presenter, multimedia creative, (social media) producer and broadcaster. You have also written a bestselling book, How to Save the Whole Stinkin’ Planet – a “garbological adventure like no other” (Penguin) – and you are the founder of four science/street art collaborations: the Co-Lab: Science Meets Street Art (Canberra 2015, 2016, 2017) and Visualising AI – Science Meets Street Art (Brisbane 2022). All this is extremely interesting for w/k, and in this article, we would like to invite you to share your thoughts on your Co-Labs, in particular how you collaborate with scientists and street artists, with the aim of better understanding the power of street art to both communicate science and excite the public imagination about science. In addition, we are curious about the artistic concepts of the street artists you have been collaborating with.

Hi. Great to be here.

As a science communicator, your work is very research-informed and science-based. Lee, how come you are interested in “mixing science with media and the arts”?

I’ve always pursued study and hobbies that are spread across the Venn diagram of science and arts. As someone who studied Drama and Sociology for my Arts degree at the same time as my Science degree, I was often jumping from one side to the other. Creating space for myself, in that overlap in the Venn diagram, has been where I have found my purpose. The science outreach I do tends to fall into one or multiple categories of media, entertainment and arts.

Why do you think it is important to bring science, science communication and arts together?

Science, science communication and the arts are already connected. Only the western education system I grew up in told me that they are separate. I think the science communication community would only be more effective and impactful if we saw ourselves as a part of the Humanities, Social Science, Media and Arts and learned more from experts in those areas. Many science communicators emphasise their relationship with STEM fields (Science, Technology, Engineering and Mathematics) but the insights and value of media and arts are just as crucial for effective science communication. Science communication is, after all, an umbrella term for communicating about a specialist technical area: science.

“Science, science communication and the arts are already connected” – How exactly do you interact with these connections in your work?

Most of my science communication work has been as a producer/presenter (live in-person, on TV and on social media). All skills involved in these roles require more than just scientific knowledge. I rely on skills I learned in Performing Arts, Social Sciences and Humanities when it comes to knowing my audience, ideation, scripting, producing and presenting.

When and how did you discover the world and medium of street art – and what is it that fascinates you about it?

I got really interested in street art during undergrad and started following social media accounts that allowed me to see more from around the world. Getting the opportunity to have a walking tour of street art in Berlin and learn about the integration between history, culture and mural there further ignited my love for the art form and its power to capture and represent elements of culture – either by holding up a mirror to it or speaking out against it as counter-culture. In undergrad I studied the sociology of resistance and crime and became fascinated with research into graffiti and street art as political and cultural resistance and expression. Street art is now commissioned, celebrated and legitimised in certain spaces (like the science co-labs, see below) but I think it’s important not to lose sight of its counter-culture roots as social resistance. It is an art form where many artists who are (now) celebrated for their talent began their craft and learnt their skills in spaces and ways that are labelled as vandalism and crime.

With street art there is no separation between space and art form. Graffiti and street art make a claim to the public space and public psyche in a way that other art forms cannot and do not. Art galleries and even public sculpture don’t connect with people in the same way or connect with the same people that street art does. Collaboration and clash are also a big part of the history and culture of street art where – unlike the commissioned and legitimised murals many of us see on social media (and, yes, in my science co-labs) – traditionally street art is not meant to remain one way with one artist; tags, artworks, paste-ups and stickers all get layered on and painted over so a wall evolves naturally over time. The act of tagging or painting over can be a very political and antagonistic move but adding to a wall can also be done in ways that show mutual respect and celebration of other artists and taggers. Street artists themselves have often come to the art form through many different paths and may have been taught by others or self-taught. I know street artists who started doing tags and so-called illegal vandalism and others who went to art schools at universities. They all have different opinions and insights to offer on the art form and its place in culture today. Some love the legitimisation of street art. Others see it as counter to the ethos of the art form itself. Some only work on legal street art walls and others do a mixture of commissioned and guerrilla art. There are also so many different techniques and materials used for street art beyond the spray can and there are so many different techniques and styles employed by those who use cans too. There’s a constant tension and discussion in the community around what is and isn’t real street art. What’s not to be fascinated by?!

Street Art, Science and Science Communication

Why is street art a great medium for communicating science? And why does it matter to use street art as a means of science communication?

Being in the public space and physically on the public space opens up so much potential for reaching people where they are. For example, I hope that my projects (discussed below) have a mutual benefit for all involved that goes beyond the use of street art as a means of science communication. I hope that science-inspired street art is as much about connecting science fans with street art as it is about giving street artists positive experiences of representing science through their art. One of the themes that emerges is breaking down stereotypes, but that goes both ways – scientists might have an idea of what a street artist is like and a street artist will have their own perceptions of what a scientist might be like but when they meet and work together; they often both have their perceptions challenged and their understanding of each other’s work expanded. The best communication is a two-way exchange rather than a one-directional broadcast and I hope these collaborations are an example of that.

How does street art enable a deeper understanding of sciences?

Street art enables understanding like any art form, but I think one unique aspect of being in the public space and representing local science and scientists as well as artists is that it really brings the message that science research isn’t some alien thing – it’s happening locally. The artworks also open up conversations between the public and scientists, who are often watching the artist’s work. All of this, I hope, builds familiarity and relatability, even if the scientific concept itself isn’t an everyday thing.

Street art and graffiti have a history of providing social and political commentary and debate. For example, in Australian cities in recent years you can often see examples from paste-ups and stickers to spray art and murals responding to or commenting on the pandemic, climate change and racism (just to name one, Scott Marsh is an Australian street artist whose work often focuses on politics and social equity, see his Instagram profile). By commissioning street art on science this offers these topics up for public consideration and response too.

Co-Labs: Creating Public Art with Street Artists and Scientists

Lee, what exactly is a Co-Lab? Please tell us more about your recent labs.

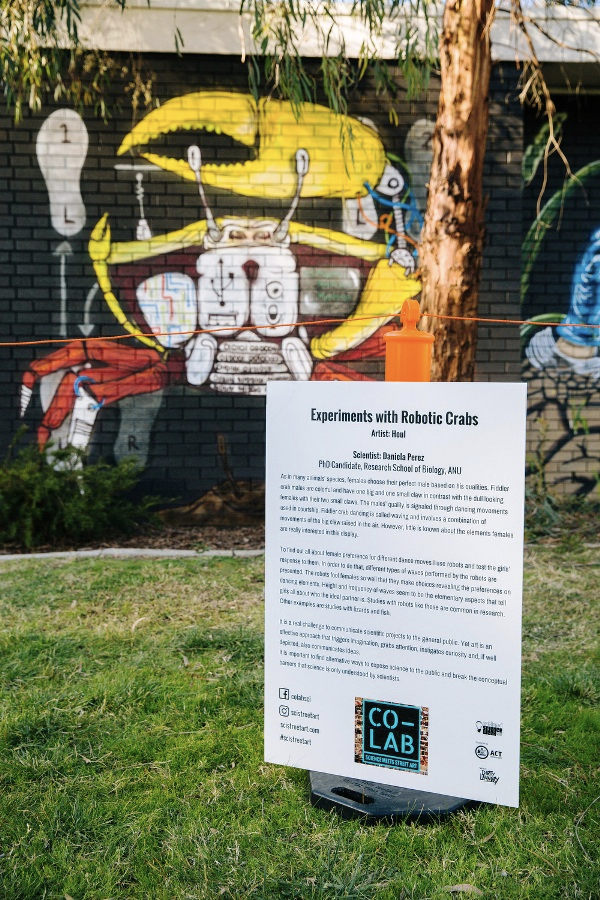

Take one scientist and one street artist. Introduce them and see what happens. The artist has the goal of creating a street art mural based on the work of the scientist. The scientist has the goal of writing a short description of their work to be displayed for the public to read as the artwork takes shape. The public is invited to not just see the end result but to come and watch the process of up to ten street artists creating science-inspired art in front of their eyes. The scientists are encouraged to chat and mingle with people and many visitors come back several times during the day to see how it has progressed. The resulting works are photographed and added to a website where they can be immortalised, regardless of how the wall’s appearance evolves.

How have your engagement with street art and your collaboration with street artists and scientists developed? What (artistic) results have these explorations led to?

Every street artist from the first Co-Lab I organised in 2015 said they wanted to do it again. Many street artists actually asked to represent research from a range of different research areas (for example across Chemistry, Biology, Physics) or talked about how they would like to continue representing scientific concepts in the future. The scientists involved have told me how much it helped them improve their communication skills. Unlike a barbeque where you can tell someone what you do in the lab and they smile and nod and move on, this conversation with a street artist had to result in some shared understanding that would form the basis of a large mural. With these stakes, it means that both people in the conversation were keen to reach some understanding in a way that doesn’t always happen when scientists talk to people about their work. Some artists have also spoken about how it enabled them to challenge their own perceptions about the particular scientific field they were representing. The scientists themselves tend to be extremely proud and humbled to have their work honoured in this way. I know of two PhD students who printed an image of the artwork at the front of their bound thesis.

Your Visualising AI Co-Lab was designed to create engagement – to spark authentic public discourse about the creation and use of AI as a transformative technology. Why is it important to visualise science and AI in public spaces?

There are a lot of public ideas about AI, what it is and what it can be used for – good, bad and ugly. There are also lots of examples where AI has been designed with inadvertent bias or impacts due to the lack of involvement of the public or diversity in AI development. Given the potential for public good, bad and ugly it’s so important that everyone feels like they can ask questions and be a part of determining the many potential applications for AI so that it can be a positive force and we can avoid unintended or adverse consequences. The grand scale and locations of the murals for this particular AI-focused set of collaborations – a mall wall, the airport, the showground and at the entrance to the Queensland AI Hub (QLD AI Hub, their website provides 360° images of the artworks) – meant that these artworks couldn’t be ignored by those in their presence. Take a look at the “For further reading and watching” section below for pictures and more details (see also my Science Meets Street Art Instagram post).

What kind of remarkable representations of AI have you had in this Co-Lab? Have you had any that have challenged common interpretations of science?

Before opening their doors to the public, QLD AI Hub asked if I could help them set up a collaboration between an AI researcher and a street artist to paint a mural in their new space. With the assistance of Lincoln Savage from Brisbane Street Art Festival we paired Dr Sally Shrapnel (University of Queensland) with artist Damien Kamholtz. I was able to be there to observe the conversation between Sally and Damien and hear them share their work and expertise with each other. AI is a great subject for street art because it can be a controversial topic. There are many different views and perceptions about AI and whether it is good, bad or morally neutral. Through this discussion, Sally shared her research into whether AI can be used to assist in the diagnosis of skin cancer and the work that she does to identify and eliminate bias that could inadvertently impact the usefulness of the AI (e.g. if it is only trained on people with fair skin, it may not adequately identify skin cancer on people with darker skin).

This collaboration gave an opportunity for an open and honest discussion about the potential public good as well as the potential for harm (if biases go unaccounted for and unchecked). This interaction (and others) I have seen between scientists and street artists often leads to expressions of mutual respect and adoration for each other’s areas of skill and talent. Ultimately there was a shared understanding that AI needs to be guided by humans and that greater understanding of AI will enable us to ask the right questions to ensure that there aren’t unintended and potentially harmful consequences of biased and unethical AI.

The part of this pair’s discussion that ultimately formed the basis of Damien’s mural at QLD AI Hub was when Dr Shrapnel spoke about Homer writing in the Iliad about golden angels as servants to Greek god Hephaestus (see for more details Layt 2021). This visual of these intelligent yet artificial beings is what Damien drew inspiration from for his mural. The resulting golden angel has very humanistic eyes. He also wanted to bring in environmental and natural themes to show that those using the space should keep in mind their connectedness and responsibility to humanity and nature.

We read online that the scientists involved were also on hand to answer questions from the audience. How did that go – the interaction with the audience? How have your Co-Labs and the resulting artworks been received by the public, researchers and other artists?

I have surveyed the public at some of these events and the thing that is encouraging is that rather than preaching to a choir – as often happens in our public science communication events – these events tend to reach multiple audiences in different ways. There is an incidental audience: the people who use the space already and just check it out as they pass by. There is an audience of people motivated to see street art in action, who also gain some appreciation for the science aspect. And there is an audience of science fans who get to gain an appreciation for the skill and work of street artists. Regardless of what brought people there, I have had an overall positive response from people.

Thanks, Lee, for this wonderful conversation!

Further resources

- Lee Constable: https://www.leeconstable.com/.

- How to Save the Whole Stinkin’ Planet, Penguin Books: https://www.penguin.com.au/books/how-to-save-the-whole-stinkin-planet-9781760890261.

- Scientists team up with Canberra street artists to paint picture of local research, discoveries, ABC News (19 September 2015).

- Lansdowne, Heather: Science meets art at Westside Acton Park, Riotact (22 September 2015).

- 2018 ANU Graduations: Alumni spotlight Lee Constable, ANU 2018.

- Layt, Stuart: Art and science converge to appeal to our ‘better angels’, Brisbane Times (19 March 2021).

- Visualising AI – Science Meets Street Art Co-Lab, QLD AI Hub (13 March 2021).

- AI Narratives & The Wonder of ‘Why’ | Cultural Champions in the Age of AI, QLD AI Hub (1 April 2021).

- Superordinary Artist Talk: AI Hub, Brisbane Street Art Festival (11 August 2021).

- Curiouser and curiouser, visualising AI, QLD AI Hub (23 August 2021).

Details of the cover photo: Lee Constable: Co-Lab 2016. Photo: Martin Ollman.

How to cite this article

Lee Constable, Anna-Sophie Jürgens and Blake Thompson (2023): Lee Constable: Founding "Science Meets Street Art" Co-Labs. w/k–Between Science & Art Journal. https://doi.org/10.55597/e8703

… [Trackback]

[…] Find More on on that Topic: between-science-and-art.com/lee-constable-founding-science-meets-street-art-co-labs/ […]