Text: Sonja Frenzel | Section: Articles by Artists

Abstract: A work of art like Markus Schrenk’s True Copy adds a provocation to the heated debates about copyright: We are confronted with an aesthetic game that raises legal and ethical as well as ontological and epistemological questions about truth and originality. What is a copy? When is a copy a true copy? And what is the relationship between the original and the copy? This contribution tackles these questions against a philosophical and cultural background. Like True Copy itself, the text is less intended to provide answers than to provide food for thought.

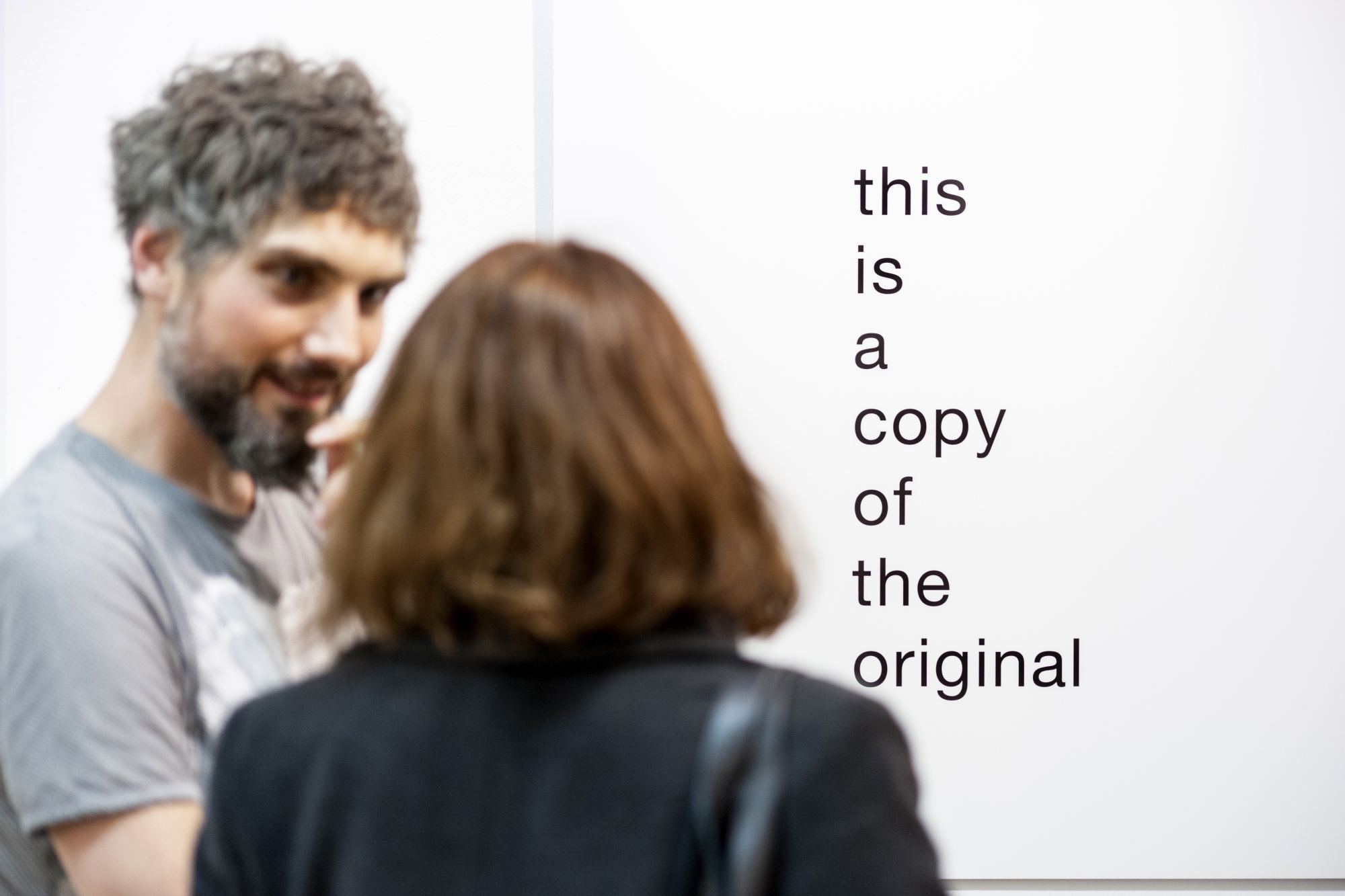

Conceived by Markus Schrenk and realised with Amrei Bahr and Reinold Schmücker, True Copy was hosted by the Centre for Interdisciplinary Research (Zentrum für interdisziplinäre Forschung, ZiF) in Bielefeld on the occasion of a workshop organised by the research group “The Ethics of Copying” (30 March – 1 April 2016). Under the title Balancing Intellectual Property Claims and the Freedom of Art and Communication, this event gathered philosophers, lawyers, and artists, so as to discuss the task and the difficulty of striking the right balance – or at least an acceptable balance – between artists’ intellectual property claims and a public interest in the freedom of the arts. True Copy resonates with these ambiguities in multiple and ever multiplying translations.

A Review by Sonja Frenzel

At a time when copyright issues are debated ever more heatedly, an artwork titled True Copy may appear as more than a slight provocation. Above all, its aesthetic play on the legal, ethical, as well as ontological and epistemological dimensions of copying challenges us into re-considering some of the most pivotal questions surrounding truth and originality: What is a copy? When is this copy a true copy? How do (true) copies relate to their original/s?

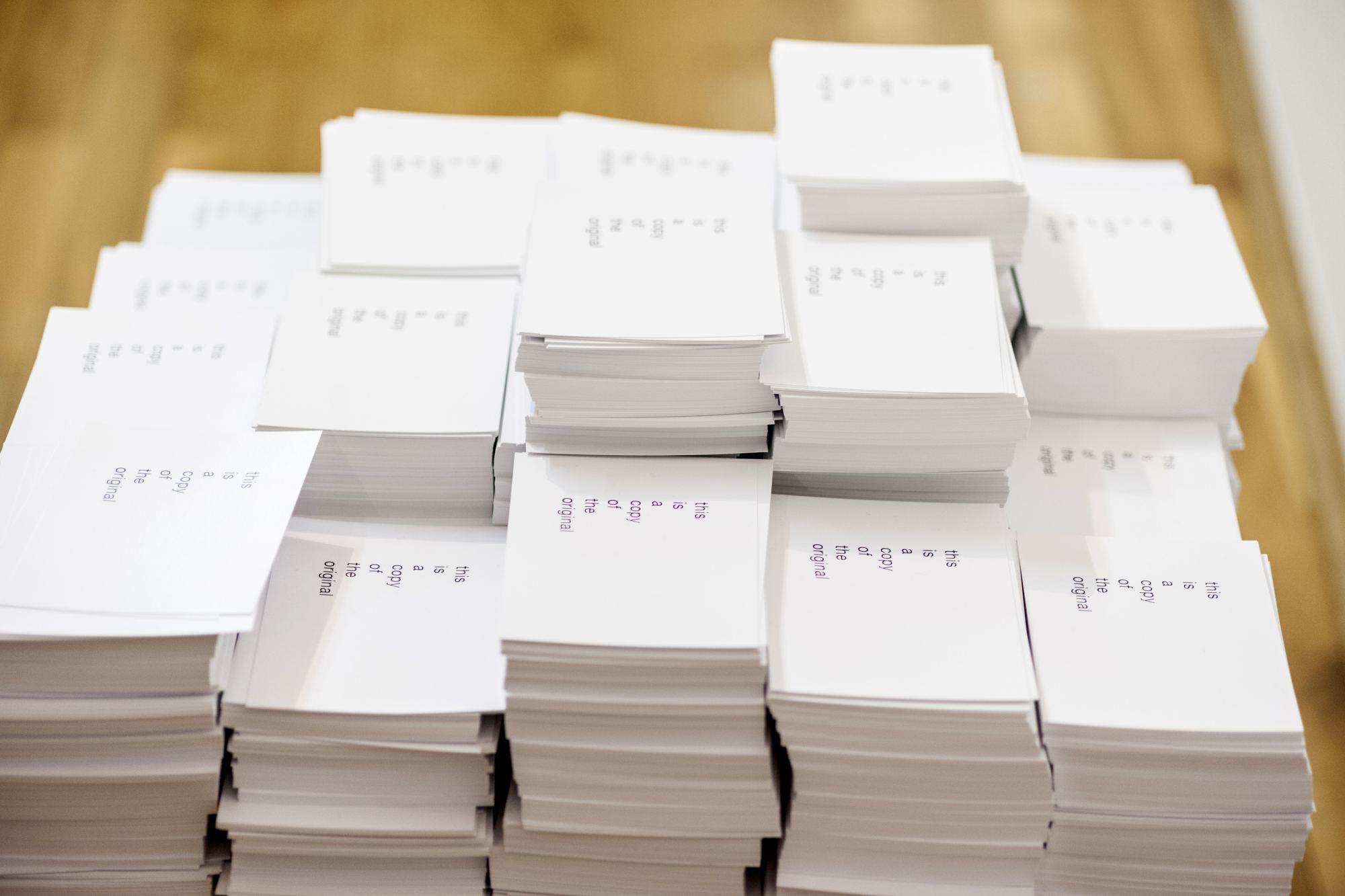

10,000 postcards proclaiming “this is a copy of the original” cannot be lying. Paradoxically though, they reproduce an original which, for its own part, must be lying. It is this original that affirms, in the first place: “this is a copy of the original”. A similar predicament is well-known in philosophical logics: The Liar is a sentence stating about itself that it is false. It revolves crucially around the unresolvable paradox of speaking the truth if it is lying, and vice versa.

By way of illustration, let that sentence be, “This sentence is false.”, where ‘this’ refers to that very sentence. Assuming that any sentence is either true or false, and never both, and never neither, we find ourselves in a paradoxical situation. Suppose, firstly, that the above sentence is true. Then it says, truly, about itself that it is false. So it is false, too. That is impossible. Hence, secondly, suppose instead that the sentence is false. Then it says, falsely, about itself that it is false. So it is true, too. That, too, is impossible.

Applying this line of argument to True Copy, we encounter comparable paradoxical relationships between an original that cannot but be lying and its (true) copies. If its copies are indeed true copies, however, the original cannot be distinguished from them. Ultimately, thus, any attempts at re-tracing an alleged original will be futile to the extent that all versions are formally identical – i.e. true – copies.

These observations gain additional complexity when considering the full scope of the artwork True Copy:

The original, as artist and philosopher Markus Schrenk claims, is not to be found among the postcards; rather, it is an A0-formatted Forex fine art print hung on a wall. In line with the above reasoning, it is bluntly lying, while its copies articulate and disseminate their alleged truth in postcard-size. And yet, it may seem that we are led to believe in an originality that is ephemeral at best, if not, in fact, an outright lie in itself.

To begin with, we might consider whether the difference in format alters the relationship between the original and its multiple copies. Does a true copy necessarily need to be an identical copy? How far may it deviate from its original source? Along these lines of inquiry, we might then note the fact that each of the 10,000 postcards carries the artwork’s title, True Copy, on its backside, whereas we cannot know whether the presumed original, with its backside facing a wall, is also labelled thus. Significantly, then, the postcards seem to offer a self-explanatory gesture, which ironically undermines the true copies’ truth: Do they remain true copies of the original when they feature additional information?

Eventually, True Copy invites us to re-think the multiple and multiplying relationships between original and (true) copy. As a presumed original is being translated into various adaptations, both the (supposedly) singular A0 print and the 10,000 A7 prints appear to be copies. Perhaps, then, the actual original is, quite simply, an idea – maybe even in the Platonic meaning – that comes to be articulated in a variety of aesthetic forms: in the particular arrangement of black letters upon a white space; in the particular semiotic meaning conveyed by these letters in their particular ordering; in the particular visual and haptic materialities of the large copy and of the postcard-sized copies respectively; in the particular potentialities of the copies’ dissemination including their perpetual transformations in and through contemporary digital media; and, finally, in the many more particular purposes these copies may be used for.

With this Platonic idea perpetually (re-)emerging in multiple materialities and (their) multiple meanings, True Copy can be seen to enter into intriguing relationships with its environment. After all, how could we be certain that the deictic reference of ‘this’ will retain the self-referential scope implied thus far?

Rather, it may be conceivable that its point of reference is, in fact, not the entire print or postcard, but, instead, the blank space on the right side. If this is the case, and if, then, a blank space is “a copy of the original”, the contested relationships between original and copy, between true and false, are intriguingly subverted once more. Is the original itself a blank space that may be copied freely and that may, in these processes of translation, be filled with meaning? Or else, do we arrive at blank – meaningless? – spaces when we attempt to copy any original?

It may further be conceivable that its point of reference lies outside of print or postcard altogether, but it might then shift to any object that print or postcard may be related to. In other words: By hanging the A0-print on a wall, does the wall become the copy of an original wall, of the Platonic idea of a wall even? By placing the postcard next to a drawing, does the deictic reference of ‘this’ shift to this artwork? What if True Copy existed as post-it stickers attachable to just about any object?

Contemplating the aesthetic and semiotic power of these deictic potentialities, we might begin to wonder whether it is possible to attach a copyright to this artwork. In other words, we might begin to wonder about the paradoxical truth claims of any creative rights to a copy of a copy of an original idea.

The Reviewer: Sonja Frenzel.

The Artist: Markus Schrenk.

Picture above the text: Markus Schrenk: True Copy (2016). Photo: Karsten Enderlein.

How to cite this article

Sonja Frenzel (2016): Markus Schrenk's True Copy. w/k–Between Science & Art Journal. https://doi.org/10.55597/e820

Be First to Comment