A conversation with Anna-Sophie Jürgens and Peter Tepe | Section: Interviews

In this interview, graphic artist and book illustrator Harry Jürgens discusses the ways in which his art builds a bridge to science, and explores the contexts in which he collaborates with scientists. He reflects on his own research activity in the artistic process, his understanding of science illustration and his artistic goals in dealing with science topics.

Preliminary remark of the editor

What kind of book illustrators and graphic artists are interesting for the online journal w/k. w/k invites artists who are either active science illustrators and/or follow a science-related approach in their work, e.g. by referring to or interpreting scientific theories/methods/results. Both are the case with Harry Jürgens. He is sometimes commissioned to illustrate a book on a scientist or to create a bookplate design on a science topic. When he illustrates scientific topics and/or texts, he acquires historical and professional knowledge, among other things, which he then uses for his artwork. Moreover, he works with historians to obtain their expert advice and with technicians to be able to apply certain techniques.

While science-related artists have been present in w/k since 2016, science illustrators have only come to the journal’s attention since the section Art-Related Scientists was established in April 2019. In this section, we also feature scientists who – in order to better communicate the results of their research to colleagues, students or even the wider public – collaborate with artists, and we call them art-related scientists.

***

Harry Jürgens, we are pleased to have been able to invite you for a conversation about the interfaces between art and science in your artwork. You originally come from the Baltic States, from Estonia, from where you moved to Leipzig in 1976, after six years of art studies, with a diploma in book illustration and graphic design. This was followed by three years of master studies with Prof. Albert Kapr at the Academy of Visual Arts. Since then, you have been working as a freelance graphic artist and book illustrator in Leipzig. The books you illustrate and the graphic art you create span literary and scientific texts. But, you also interpret scientific themes in the medium of printed graphic art, so-called bookplates, which is why you are interesting for w/k. The Leipzig writer Volker Ebersbach once wrote about you: “Jürgens infuses the books he illustrates with his light. Nothing better can happen to them.”[1] By way of introduction, we would like to ask you to briefly introduce your work as an illustrator, especially with regard to science illustrations. We will talk about science references in your graphic art and bookplate design in the second part of the interview. Which books or topics have you illuminated so far – and which sciences?

I illustrate books from the field of world literature and classical literature, where themes from antiquity and mythology emerge as focal points, which are particularly evident in bibliophile editions that I design for German publishers and abroad. Many of the books I illustrated before 1990 were devoted to historical themes. At that time and until recently, I have worked as an illustrator and book designer for the Miniaturbuchverlag Leipzig (a publishing house specialised on miniature books). For the volumes Tesla and Werner von Siemens from the series Wissenschaft und Okkultismus (Science and Occultism) I created calligraphic designs for the covers and slipcases, for example. In the field of children’s and youth books, it is, above all, adventure and travel stories that inspire me artistically with their fantastically diverse settings. My illustrations also appeared in the ‘adult version’ of this genre, in Helge Timmerberg’s novel In 80 Tagen um die Welt (2008) and its sequel African Queen (2012), as well as in Dennis Gastmann’s novel Atlas der unentdeckten Länder (2016), which I partially illustrated. School and textbooks[2] as well as didactic drawings and factual or technical drawings for scientific material are also among my interests as a book designer.

Are the last works you just mentioned science illustrations?

The medium of illustration allows the artistic imagination to unfold. In the drawings I referred to – created for the University of Leipzig (Herder Institute) in a long-term process, together with a commission of professors for a volume in the field of science communication/intercultural communication – the visualisation of information, correct reproduction of scientific material and its communication were the primary concern. Here, artistic interpretation took a back seat to concrete factual references. For me, such factual representations are didactic drawings, not illustrations. I illustrate scientific topics in the medium of printed graphic art (etching). For example, in my bookplates I interpret medical or technical historical phenomena with artistic-graphic means.

This is very interesting! Before we explore the science-related content of these works, could you briefly explain what a bookplate is?

Bookplates (also known as ex-libris) originated with the printing of books as book owners’ marks, which means that their function was originally to mark the book holdings of a particular library. Because of this function, heraldry was a canonical genre of early bookplate art that was popular throughout Europe in the 16th century. Originally, then, bookplates were a branch of commercial art, but over time they became more and more detached from the book. Nowadays, bookplates are primarily objects for exchange and collection. For example, ex-libris are commissioned from artists as exquisite gifts for important anniversaries or weddings, or as memorial art – to visualise and remember ancestors. Critical voices, however, are heard again and again, criticising both the loss of the reference to, and detachment from, the book, and new computer-graphic approaches that compete with historical techniques (such as etching or copperplate engraving) and thus – from this perspective – threaten a tradition that was long characterised by specific graphic techniques and formats of its own. Of course, there are also other voices that see progress in the vitality of the tradition. In any case, many contemporary bookplates have elements of what is called Freie Grafik in German (a Freie Grafik is an artwork that the artist develops independently, without commission). I myself refer to my works as freie grafische Ex-libris (or ‘independent’ bookplates) and try to maintain a relationship with the book, if only a minimal one. It is important to me that my bookplates at least indirectly refer to the tradition.

Against the background of this graphic tradition, it seems natural that – as you suggest above – historical or historiographical themes have a special place in your work.

Yes, many of my bookplates are dedicated to specific historical phenomena on which I do intensive research. In this sense, the preparation of a bookplate composition is always associated with research.

Author Helma Schaefer, who has known your work for many years, lucidly wrote that your art – modern bookplates – “build an artistic bridge between poetry and visual art”[3]. In what way do they bridge the gap to science? Please give us a few examples.

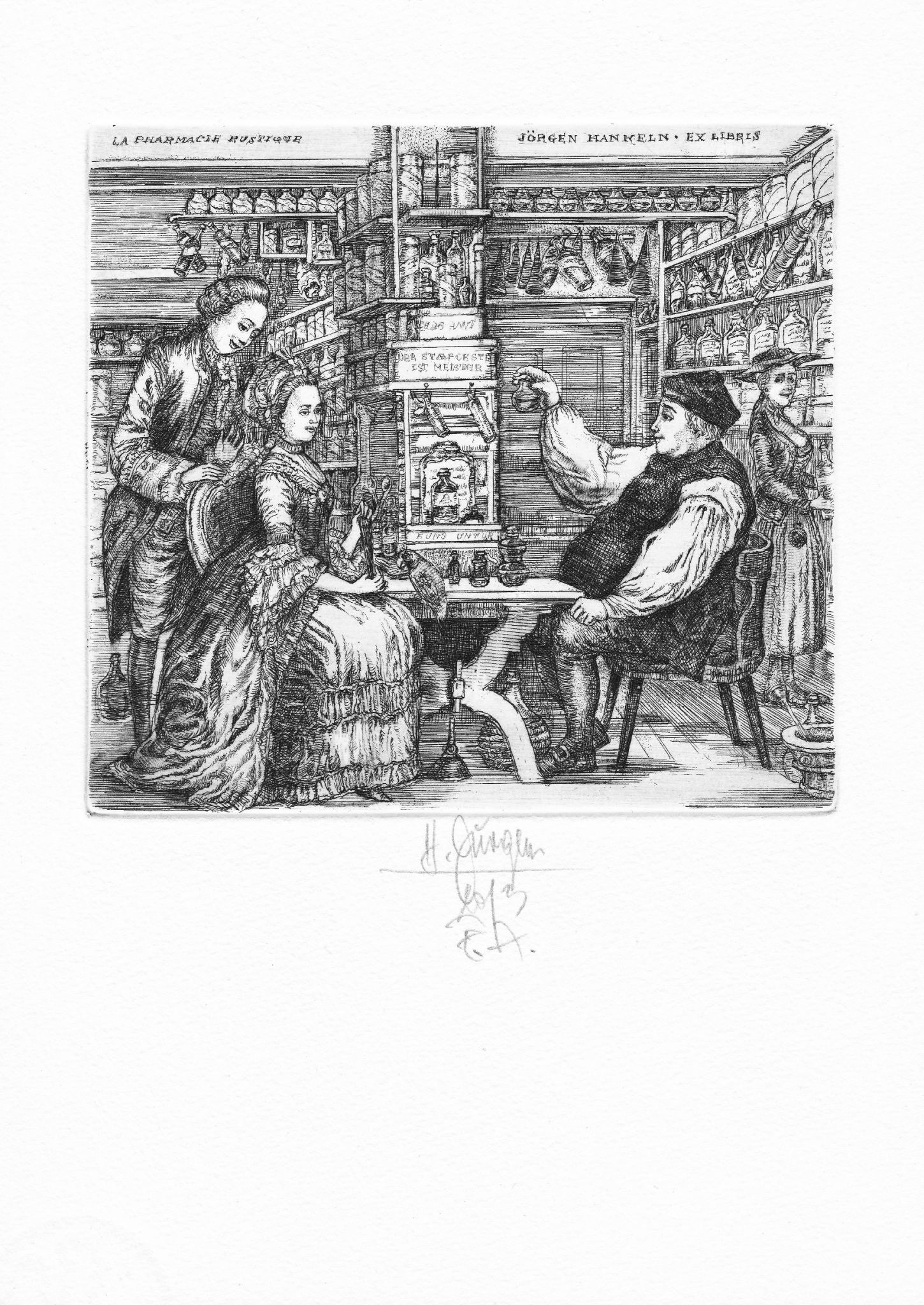

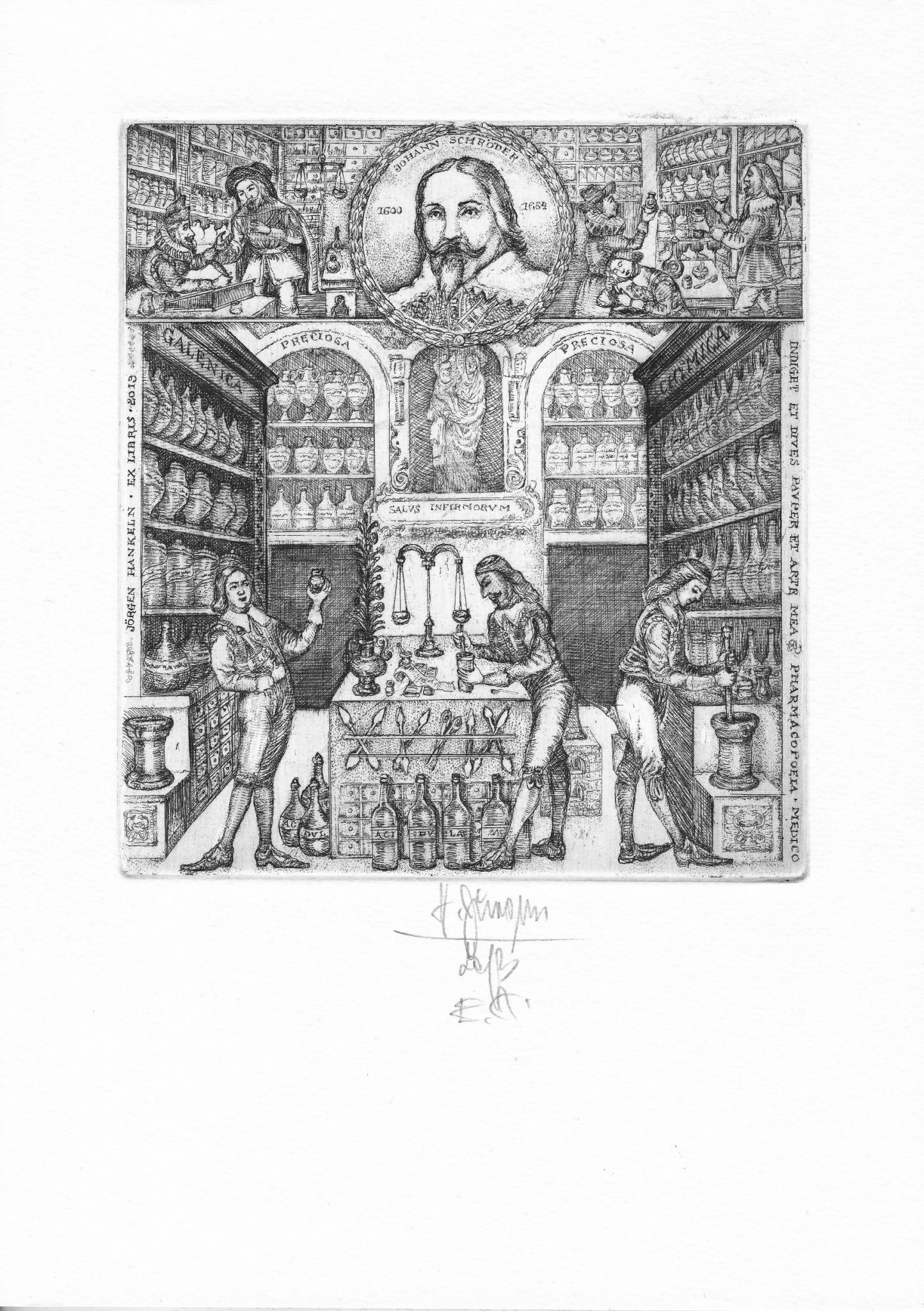

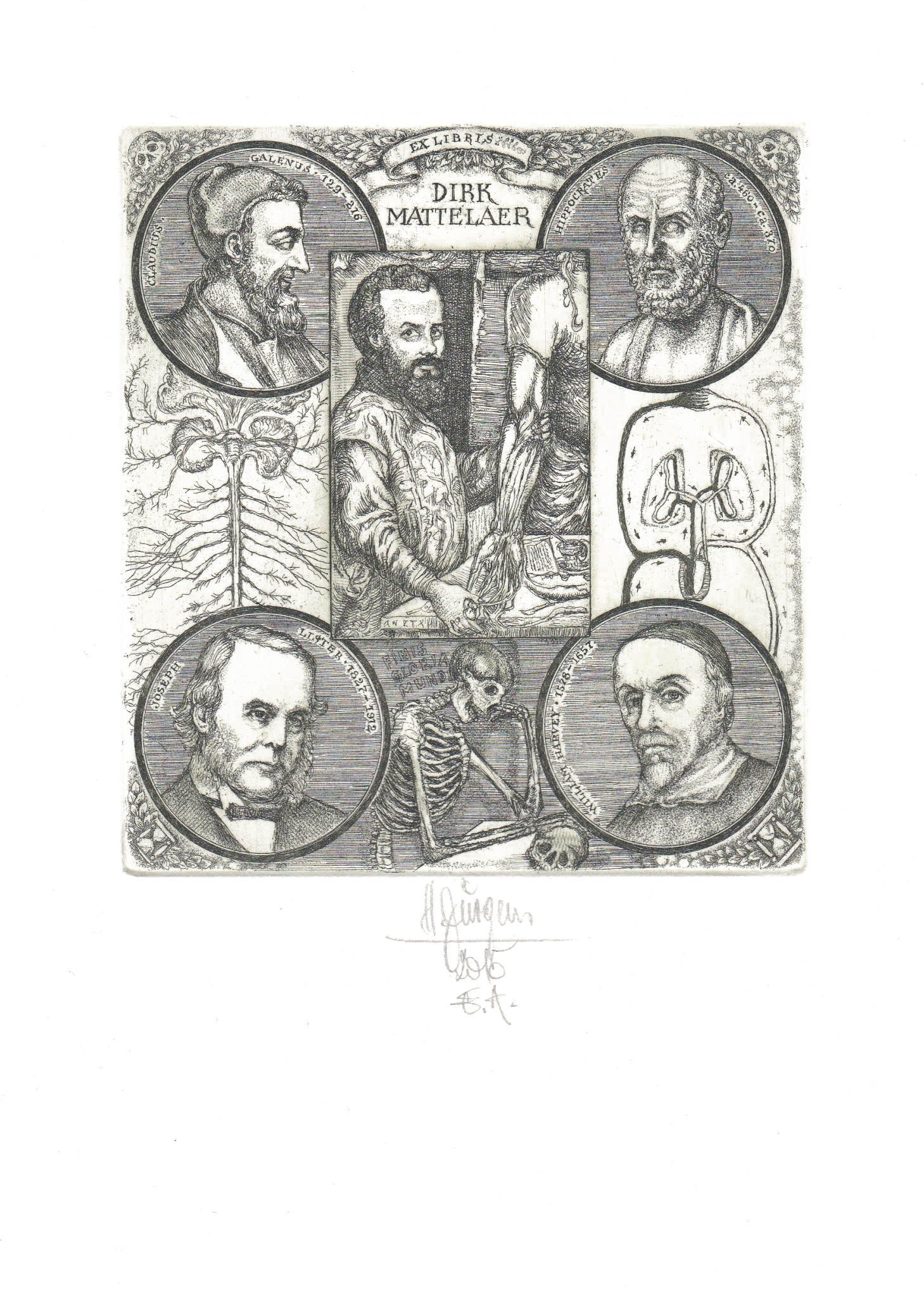

For my graphic art on the history of medicine and a bookplate series on historical pharmacies, for example, it was necessary to study baroque interiors as well as contemporary instruments and building materials with their respective specific surface structures in order to capture as accurately as possible the state of knowledge of the epoch depicted, its visual language, and the epoch’s specific view of the body, its anatomy. At the same time, people depicted in these artworks cannot look like us today. Therefore, an essential part of my preparations is always the study of costume. This is especially true for projects that show historical uniforms (for example, 18th-century military uniforms), where every button has to be in the right place. In addition, in such cases it is important that the respective weapons are worn at the correct angle. And in the case of coloured bookplates, the colouring must also be historically correct. Besides the historical ‘main material’, I therefore also study costume history and military history. Since no photos, films or other visual documentation exist for many historical subjects, reliable descriptions have to be systematically sought and found. The study of non-fictional and fictional publications is often part of my work. My clients, in many cases scholars and researchers themselves, are happy to advise me in more complicated cases.

How concrete or ‘scientific’ are the researchers’ ideas when they describe what they want for a graphic art project to you? Are there any specifications for a science illustration on the part of the client, and if so, what are they, and what does your cooperation with scientists look like?

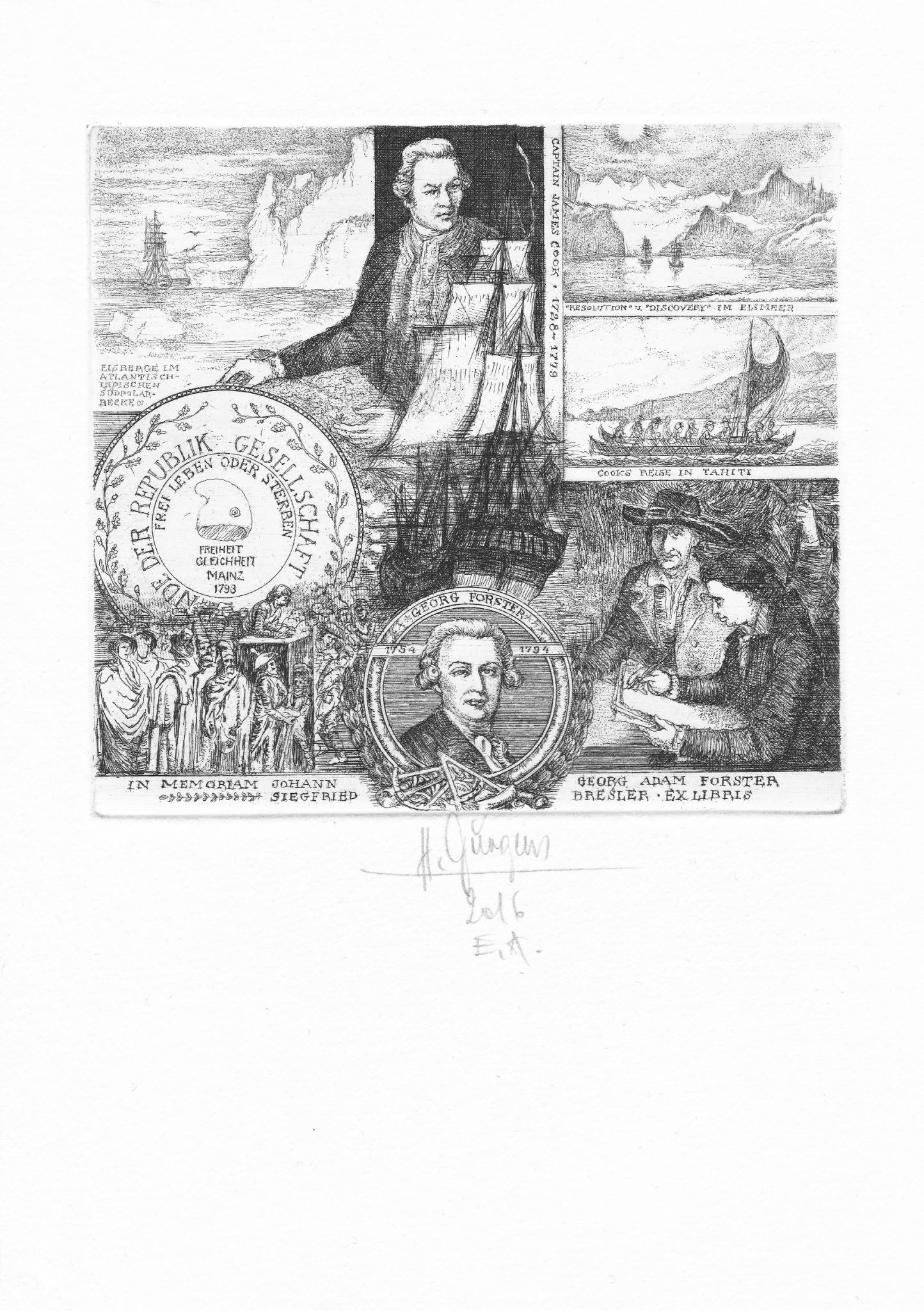

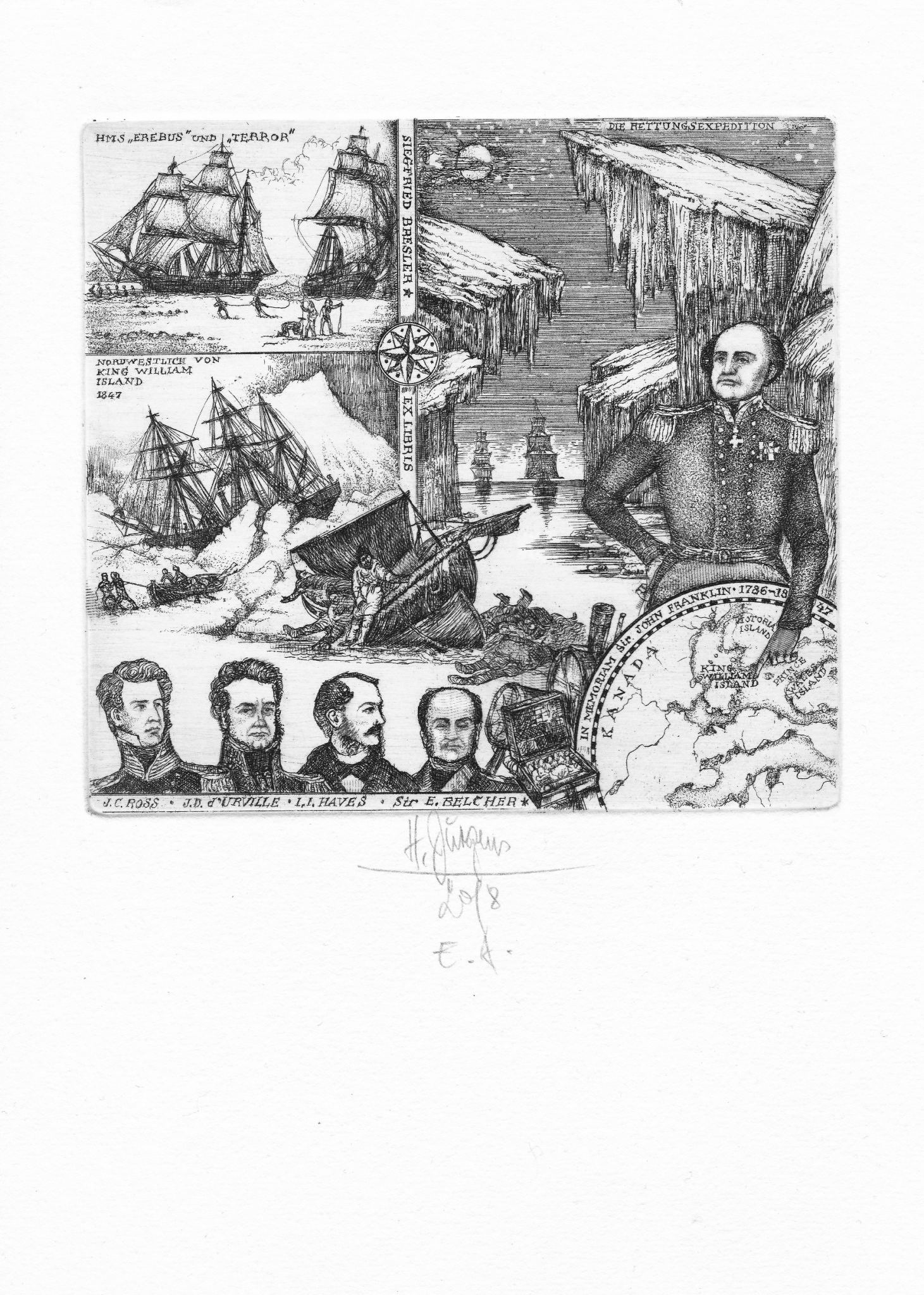

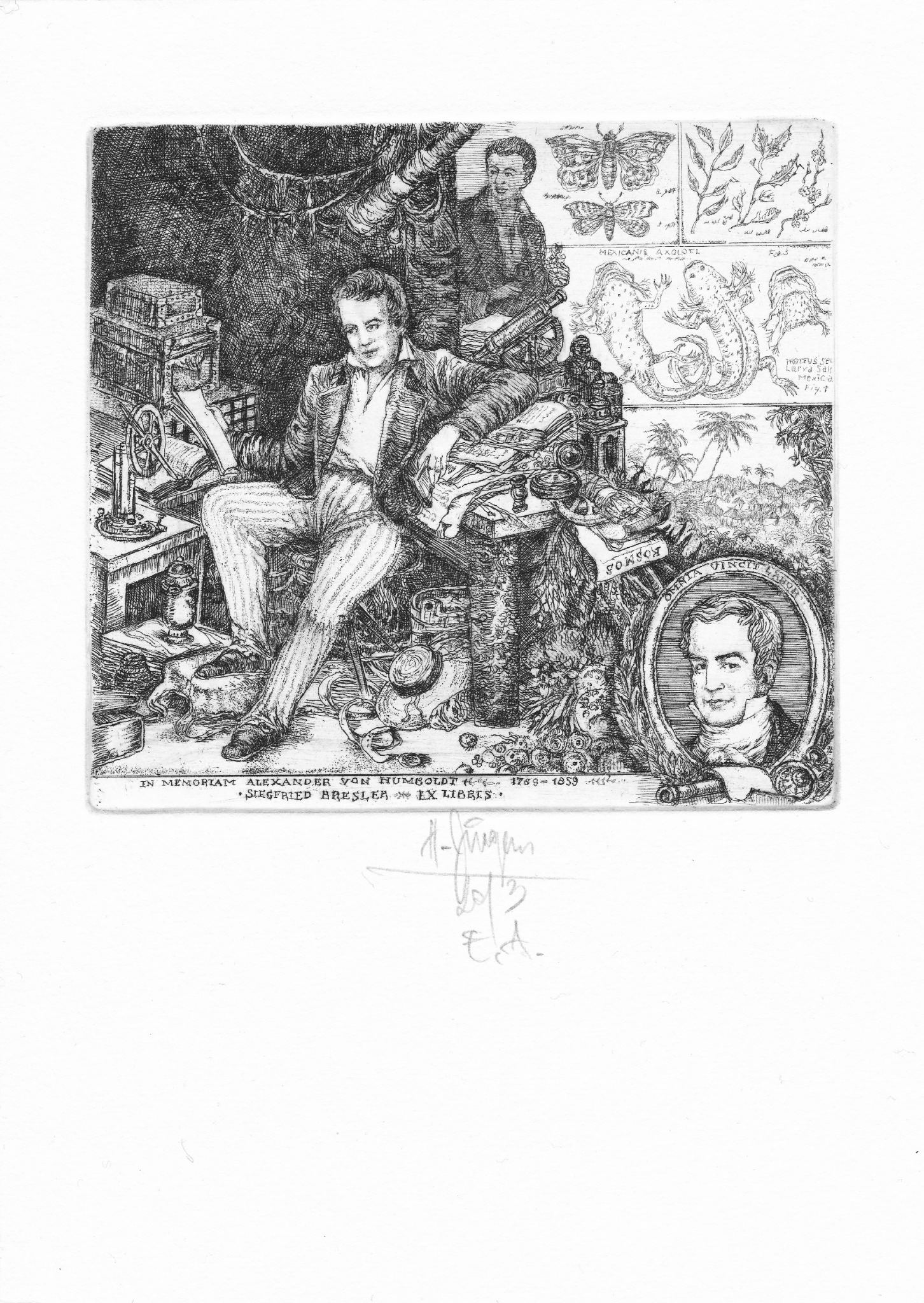

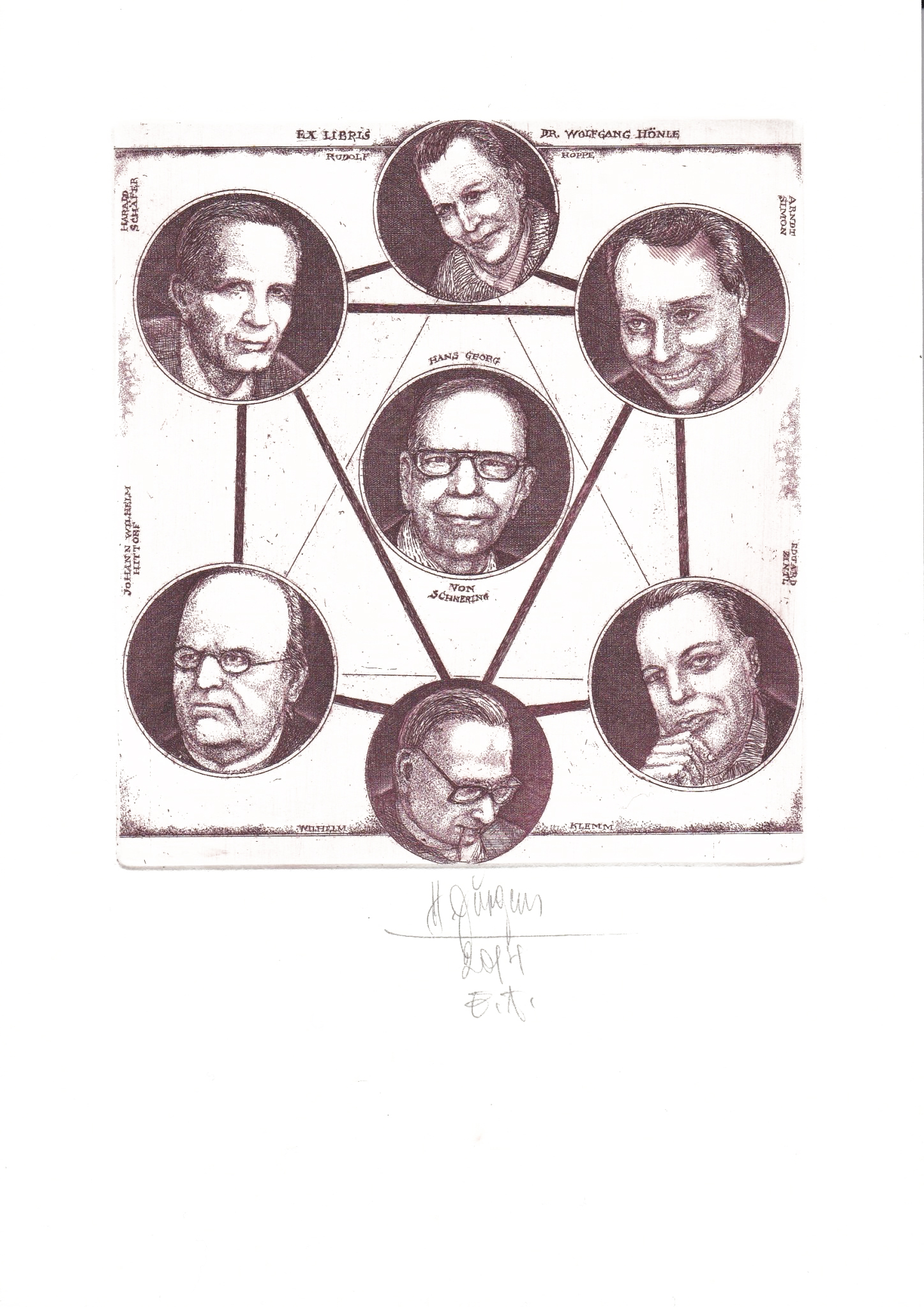

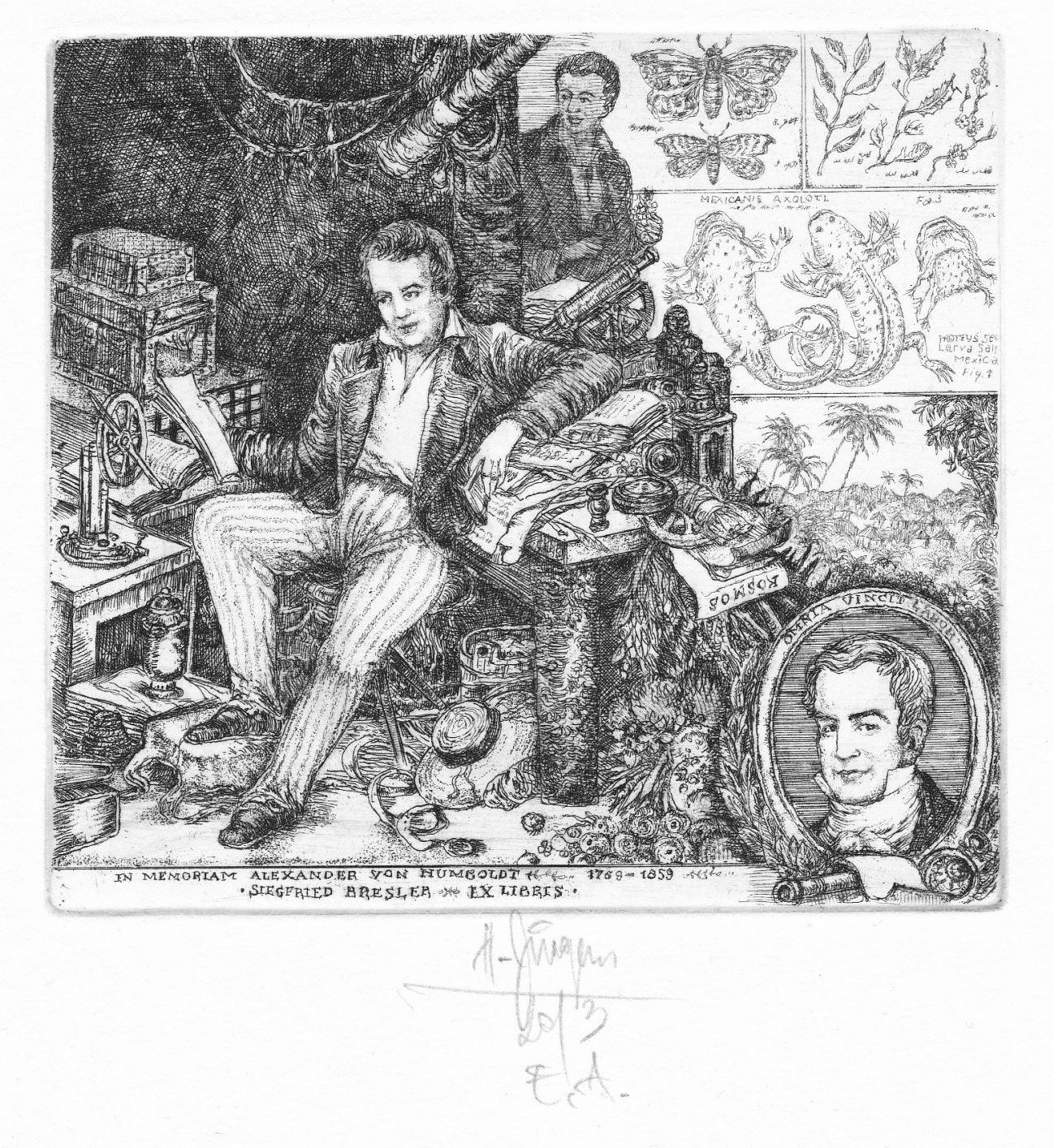

The specifications of the clients are different and very individual. In most cases, such as my ex-libris series on naturalists and explorers, in which works on Alexander von Humboldt, Sir John Franklin, Johann Georg Adam Forster and Friedrich Wilhelm Ostwald have been created so far, a scientifically- and culturally-important personality was suggested to me – whom I then ‘travelled after’ in my preparations, studying encyclopaedias and specialist literature. My compositions show my own artistically realised voyage of discovery around the respective theme. In these works, I try to show connections between the respective scientific and technical status of the time, its methods and means of generating knowledge (for example in the field of geography or cartography), systems of order and milestones in the lives of the researchers. Ideally, this helps us to better grasp and imagine the image they had of the world – which I understand as an achievement of science illustration in the broadest sense. For some scientific topics, I also consult with experts. At the moment, for example, I am working on an artwork that conveys or visually explains the very specific state of research on a fossil, which requires close consultation with a palaeobiogeochemist. In other cases, as in a bookplate on Nobel Prize winners in chemistry, the client suggested focusing on portraits of the scientists, which is a very different, but no less appealing, approach to the subject of researcher personalities. In many cases, I am sent material that I – following possible wishes and/or my ideas – use to shed light on my artistic inspiration, place in (new) contexts of meaning and thus graphically illustrate. My science-related bookplates are preceded by a methodical process of research and recognition, of ordering and reassembling, very often in collaboration with scientists, the result of which is art. In this type of bookplate, it is the tension between correct historical details and temporal backdrops, contextual backgrounds and technical accuracy on the one hand, and my interpretation and composition, my artistic vision, on the other, that pleases me and excites clients.

Graphic artistic fantasy meets scientific reality?

You could put it that way. Peter van der Weerdt wrote about this in 2015: “Knowledge and artistic creativity are required at the same time.”[4] Therefore, I have always been fascinated by anatomical drawings, especially those from times that preceded our state of knowledge and, from today’s perspective, have fantastic elements. They are reminiscent of early world maps that placed dragons and mythical creatures in yet-unexplored or presumed territories. Although I feel stylistically connected to Dürer and Cranach, whose craftsmanship impressed me even as a student – later I also discovered the Danube School around Altdorfer – I am also inspired by the figurative compositions of Mannerism, which have impossibly twisted, funny and literally-fantastic anatomies, and yet, like Arcimboldo’s illusions, have something realistic about them. Similar things can be said about Piranesi’s fantastic-realistic architectures in Utopia, about works of the Viennese School of Fantastic Realism (Ernst Fuchs) and especially about Albin Brunovský’s literally fantabulous graphics. As part of my master’s studies in the early 1980s, I was able to do additional studies with Brunovský in Slovakia.

What artistic goals do you pursue in your engagement with science topics?

I try to combine artistic creativity with technical quality and drawing ability.

The Dutch graphic art collector Peter van der Weerdt, who has already been quoted here, wrote about you that in several fields, especially the history and literature of antiquity and general cultural history, you have “acquired such extensive knowledge and acquired such a special empathy” that you “actually deserve an honorary doctorate for it”.[5] Would you say that you are a graphic art researcher?

I am first and foremost a draughtsman of pictorial fantasies, a storyteller with ink and etching needle. I carry out the research and extensive preliminary studies outlined above on any subject, whether a project is devoted to Goethe’s Roman Elegies or Lucian’s Hetaerian Conversations, takes Ali Baba and the 40 Robbers as its theme, or the Marquis de Sade or Beethoven. Science-related themes are appealing to me because – more than other areas such as antiquity or mythology, which I cover as a graphic artist – they release creative potential at the intersections between historical depiction or correct factual representation and fantasy. Certainly, I do research in the context of my work, but I am also, since it is ultimately an artistic process, a graphic artist explorer.

Thank you very much for your time and the interesting conversation.

Details of the cover photo: Harry Jürgens: Alexander von Humboldt (Opus 2013/492). Photo: Harry Jürgens.

For further reading (in German)

H. Decker: Schätze der Exlibriskunst – Von Johann Baptist Fischart bis Ernst Jünger – Dichterexlibris, Frankfurt a.M. 2006.

Deutsche Bücherei Leipzig, Deutsches Buch- und Schriftmuseum: Exlibris – Aus dem Buch- und Bibliothekswesen, Leipzig 1966.

V. Ebersbach: „Mythen in Filigran. Neuere Radierungen und Federzeichnungen von Harry Jürgens“, in: Illustration 63 – Zeitschrift für die Buchillustration 2003 40/1, S. 13–19.

T. Naegele: Reinhold Nägele – Exlibris, Stuttgart 1989.

N. Ott: Exlibris – Zur Geschichte ihrer Motive, ihrer Gestaltungsformen und ihrer Techniken, Frankfurt a.M. 1967.

H. Schaefer: „Die Bilderwelten des Harry Jürgens. Betrachtungen zum 60. Geburtstag des Graphikers und Buchillustrators“, in: Graphische Kunst – Internationale Zeitschrift für Buchkunst und Graphik 2/2009, 3–8.

H. Schulz: Einführung zur Ausstellungseröffnung „Harry Jürgens – Metamorphosen“ im Städtischen Museum Aschersleben, 12. Oktober 1997.

„Filigrane Radierungen voller Perfektion“, Volksstimme Wernigerode, 02.10.2003 (zur verlängerten Ausstellung von Harry Jürgens in „Angers Hof“).

[1] Volker Ebersbach: „Metamorphosen. Zu Graphiken von Harry Jürgens“, in: Illustration 63 – Zeitschrift für die Buchillustration 1998 25/1, 3–7, here 5.

[2] Jürgens’ didactic drawings can be found, for example, in: Deutsch komplex – Ein Lehrbuch für Ausländer – Mittelstufe I und II, developed under the direction of Hildegard Jacobeit and Martin Löschmann. Sachsenbuch, Leipzig 1993 (both); Langenscheidts Schreibübungsbuch Chinesisch – Eine Einführung in die chinesische Schrift. Langenscheidt, Berlin u. München 1996;und Deutsch XII – Lehrbuch von Helle Kasesalu, Ellen Liiv und Mare Lillemäe. Kirjastus Koolibri, Tallinn 2005.

[3] Helma Schaefer: „Die Exlibriswelten des Harry Jürgens“, in: Frederikshavn Kunstmuseum & Exlibrissammlung: Harry Jürgens, Exlibrispublikation 557 / Exlibriskünstler der Gegenwart 73, 2013, no page numbers.

[4] Peter van der Weerdt: „Opus 500 des Leipziger Exlibris-Künstlers Harry JÜRGENS“, in: Mitteilungen (Journal der Deutschen Exlibris-Gesellschaft) 2015/2, 53.

[5] Van der Weerdt 2015, 53.

How to cite this article

Anna-Sophie Jürgens (2021): Science in Bookplate Design: An Interview with Graphic Artist Harry Jürgens. w/k–Between Science & Art Journal. https://doi.org/10.55597/e7038

Be First to Comment