A conversation with Peter Tepe | Section: Interviews

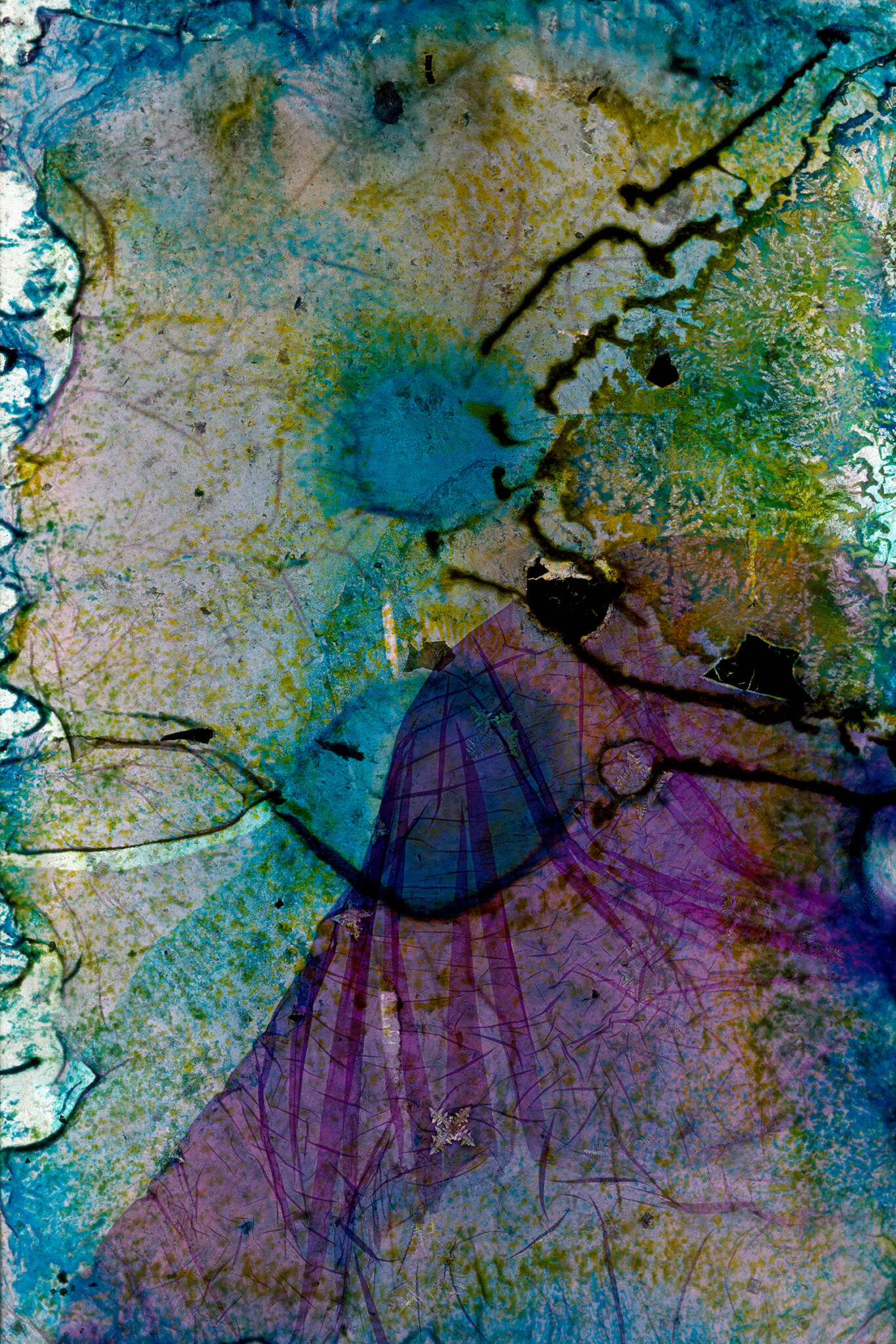

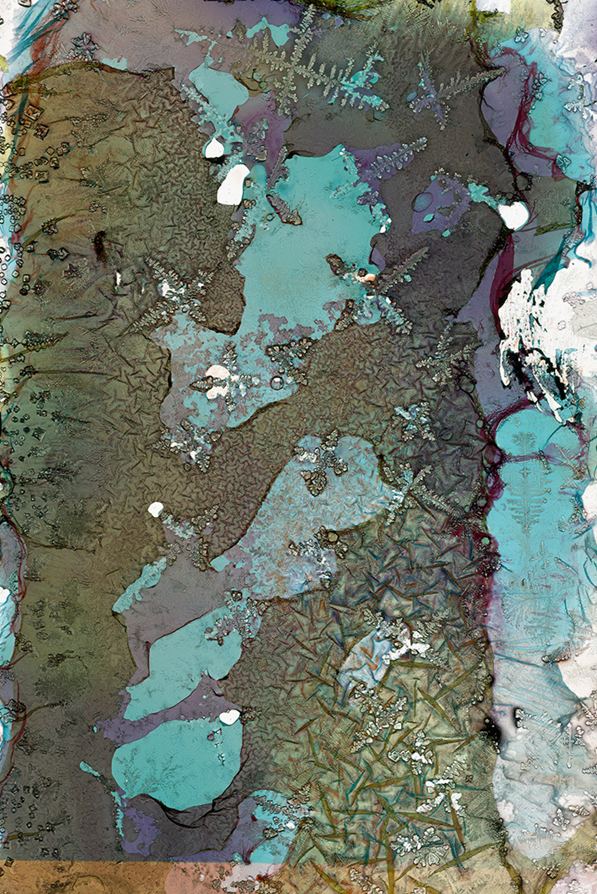

Abstract: Roland Regner has embarked on a radical photographic project. He is transforming his entire archive of biographical photographs. The conversation presented here refers to several series in which he exposes biographical photos to a certain bacterium. This transforms them in such a way that, when viewed, they are no longer recognisable as biographical photos. For this project Roland has teamed up with the Microbiological Institute of the University of Zurich. This artistic endeavour is linked to the idea that photographs never portray reality objectively.

Roland Regner, your cycle of works Arché includes several photo series where you collaborated with scientists and experts, and still do so. We’d like to explore this interesting collaborative endeavour in a bit more depth for w/k. I’d suggest we do this in two segments: in segment 1, we’ll look in detail at your approach to the two series Slides / Negatives (Dias / Negative) (DN) and Petri Dishes (P). Then we’ll outline how you collaborate with scientists in these series. Finally, in segment 2, we’ll define as precisely as possible the artistic concept that you are adopting.

Ok, I’m happy with all that, yes.

In 2012, you took your entire archive of biographical photos – in other words, every photo containing you as the subject, from the point you were born right up to the present. And you began transforming them, in a very special manner. As we said, in segment 1 we will first describe the typical procedure you used for the selected series. Can you use one biographical photo as an example?

I can’t, unfortunately, because there aren’t any originals left. So I’ll start with two transformed pictures – one from each series.

What have you done with the originals?

If they were a slide or a negative, I exposed them to a cultured bacterium.

What happened when you did that?

I’ll demonstrate that using the selected examples. The bacteria have transformed the information and colour layer of the slides/negatives. Beforehand though, I write down the main content of each photo and the year when it was taken, e.g. Person Easter basket Meadow Plants 1987. Also, I have assigned each photo to one of the two series and given it an index number, e.g. DN-0206. The only way a viewer can recall an original photo is by putting a picture together in their mind based on their own biographical photos / pictures of themselves.

The transformation seems a long, complex process. Where did you start?

I focused first on collecting all the biographical photos. So I had to find my own photos of course, but then also those that were kept by my parents, friends, relatives, older friends from the past and ex-partners. It wasn’t easy, especially for my parents, when they realised what I intended to do. I mean, these were unique items that meant a lot to them, like the picture of my first day at school hanging in my parents’ living room.

Actually, for that photo, all that was left was the photo print. So I transformed it using sodium hydroxide solution and put it in another series, Photo prints front (FV). And that’s the version that my parents now have in their living room.

This is an unusual project. Could you, at this early stage, perhaps already give us a first clue as to why you decided to do it this way – with the knowledge that if you carry out the project as planned, it would mean that not a single biographical photo of you would be left?

This project was motivated by questions related to the media. But it’s not actually true that there are no more biographical photos of me left. The colour information on the substrate of the transformed images is still there, just arranged differently and/or more chaotically.

A central question was: Can the transformed images still be interpreted as biographical photos? What survives in the memory and how is it reconstructed and adapted to the reality of the here and now? You know, we are actually all permanently redefining our relationship to what reality means.

Then you placed the photos in a cultured bacterium. How did you go about that?

For the DN series, I asked the Microbiological Institute of the University of Zurich whether they would be interested in undertaking a project of this kind. After presenting my project, the director Prof. Reinhard Zbinden first asked me whether I was out of my mind. But approval was then given, and a test phase with different bacteria began, lasting about three months.

What was the aim of this test phase?

The aim was to leave the substrate material of the slides/negatives in its original consistency, while the information layer contained on it was to be transformed. And of course the institute did not want it to be a highly contagious or dangerous bacterium. I also had to work following the usual safety standards there. Despite doing so, I did get infected once.

What happened next?

After finding a suitable bacterium (an intestinal bacterium of the Shewanella group), I began to transform the first 160 or so photos together with Prof. Zbinden. Each individual slide/negative was placed in a petri dish with nutrient fluid and then infected with a high concentration of the bacterium using a syringe. The next step was to move the petri dishes into a large, walk-in incubation chamber that ran at a constant high temperature, similar to human body temperature.

I was given a guest pass to access the institute and so I could check every two days whether the transformation had taken place in any of the pictures. Generally speaking, the transformation took two days to six weeks. depending on the age, manufacturer (Kodak, Fuji, Agfa, etc.) and type of either the slide or negative. Once it was no longer possible to recognise the original image information, I halted the transformation process and dried the result of the transformation.

After a three-month interval, the remaining approx. 200 slides/negatives were then transformed. After that, all the slides/negatives and petri dishes were high resolution scanned, which took about a year.

During the transformation, does all the information disappear?

No. The important thing is that the information is being transformed – it does not disappear. I was able to check all the slides/negatives at the institute every other day over the entire period, so not a lot got lost. The information was and is still there – it’s just arranged differently.

Nevertheless, the transformation did result in a minimal shift of information during the drying process. The residual data remained stuck on the petri dish, so I had to scan all the petri dishes to ensure complete preservation of the information. This resulted in the series Petri Dishes, which wasn’t really planned that way.

So, let’s just recap here. You decided to transform all photographic material of yourself throughout your life up to the present: slides, negatives and photographic prints, X-ray pictures of you in various past situations are all subjected to specific processes developed for the individual substrates. Does this artistic endeavour of yours have anything to do with some sort of life crisis? Because if so, then your artistic approach would also express a desire to break with the past and start all over again.

I have been asked that several times. Lots of people see this as a radically existentialist approach – a kind of progressive damnatio memoriae that I am consciously pushing myself.

But, no, I didn’t do it in response to any feeling of going through an identity crisis or life crisis when I started the project. Neither was it an attempt to come to terms with my past. At least, not one that I was aware of.

If it’s not an attempt to overcome some kind of life crisis, what is the backdrop to your project then?

I felt I was at a crisis point artistically. In 2012, I was on the Master Fine Arts programme at Zurich University of the Arts. I had already been working with biographical photographs for some time, although the work did not focus on photographs of me.

I wanted to take the concept of the black body from the field of physics, especially quantum physics, and cross relate it to humans. The black body means a body that completely absorbs electromagnetic radiation hitting it at any wavelength, without reflecting any of the radiation. In purely scientific terms, there is no such thing as a black body; or at least, it cannot be produced such that it represents an ideal image to base practical investigations upon.

I posit the theory that an idealised black body could fully and all-knowingly absorb into it everything in the outer world. The idea was to connect this theory of the black body with the term Black Box by Vilém Flusser from his book Towards a Philosophy of Photography. All psychological and cognitive processes of a person were supposed to be captured by the camera.

I burned biographical photos of other people and used them to blacken the inside of the camera. I did this because I wanted to charge the camera up magically to a certain point and produce new photos. This plan failed at the first stage however, with the pictures themselves. Looking at the photos, all you could see was a black mess on the picture. There was nothing magical about the picture at all. And I couldn’t ultimately conclude what I actually wanted to photograph in terms of motif.

But the concept of the black body was something that continued to attract me. Even knowing that it wasn’t really possible to bring my concept to realisation, in fact being determined to try for that very reason. Maybe I’ll give it another go at some point.

Can it be said that through the reorientation you have described, you have resolved a particular artistic problem? Or to put it another way: What artistic goal is achieved by this lifetime project, whose ideal outcome is that the only biographical photos of you left will be ones that are completely transformed?

When I decided to do all the work myself and when I settled on the concept of transformation, the problems that had caused my earlier project to fail were solved.

With the new project, I’m concerned with elementary questions about photography as a medium of memory and preservation and, connected to this, about photographic materiality and manipulation. This can be said to be my overriding artistic goal.

Does your artistic project affect the way you live your life, or do you expect there to be any effects from it in the future?

Looking at photos with my family isn’t that easy any more. Doing this with the transformed images, I try to reconstruct the image of a photo in my head and, at the same time, to link it to a certain feeling. But that brings us back to the question of how far such images and the feelings associated with them are adapted in the here and now.

In normal everyday life, though, I haven’t noticed any major negative consequences so far. The only exception, of course, is when I tell people about it and am then accused of acting in a self-directed aggressive way. Or I get told that I should also think about my family.

These statements show how important the biographical photo still is. Especially in this age of Facebook, Instagram, Twitter, etc. We now live in an image culture that constantly makes assertions but is seldom questioned.

With my work, I try to address precisely this pre-designed obsolescence by transforming the information layer. The exact same level of visual coding that characterises the promise of truth in photographs thus becomes comprehensible through the intervention as a fragile film on technical surface structures.

Clearly, you are breaking new ground within the field of photography with your approach.

The new thing about my work is the systematic transformation of my entire personal photographic archive. Nothing like this has been done before in this way. At the moment, I’m working on the transformation process of the digital photographs.

Are there any photographers that influenced your artistic concept in any particular respect? Do you take any photographic approaches that already exist and develop them further?

Not directly. Yes, of course there are artistic works that relate to my project. Those works are mainly ones that deal with the topics of archive, transformation and falsification of memory using photographic images, such as those of Christian Boltanski for example.

Your photos are greatly evocative of informal painting. Did painting play any part in you developing your artistic concept?

No. But my work has often been associated with abstract or informal painting. I can understand this from the purely visual and aesthetic viewpoint, of course. The random principle I employ by using intestinal bacteria, caustic soda, etc., also reinforces this association. But there was no great spontaneity involved in my development of the artistic concept: it was all thought out and planned. And for me, it was always about photography, never painting.

Which other forms of photography do you fundamentally distance yourself from?

From concepts that genuinely claim to be able to depict reality and truth. When photography was invented, the aim was to rid the artistic vision of subjective inputs so that objective images of how things really are could be created. It was already known at that time that the way in which a photographer arranges subjects and perspectives is relevant for the final image. However, this was pushed into the background at that point due to the fascination with the technically advanced camera. There was – and still is – an almost insistent belief in the objectivity of technical processes.

So the medium of photography was said to be able to depict reality objectively, meaning that what was depicted on the two-dimensional image corresponds 100% to what appears in front of the camera. Modern times have shown in cultural and visual history and in the arts in general that such an assumption is problematic.

But beyond these fields, in the everyday use of images, the truth of the photographic image is rarely, if ever, doubted. We want to trust images.

Is there a link from this to your project?

Yes. This fundamental trust in the true accuracy of photographs shows itself particularly when it comes to personal photographic archives. As soon as a photo becomes part of the biographical context, any argument against the belief that the photo accurately represents the realities of the situation evaporates. I mean, who wants to have it in their head when looking through their entire life in photo albums or on screens that they cannot rely 100% on the photos backing up their own identity ?

Thank you very much, Roland Regner, for talking to us and I look forward to the next time we meet.

Details of the cover photo: Roland Regner: Arché. Exhibition view Erinnern at Q18, Cologne (2018). Curated by Michael Stockhausen. Photo: Roland Regner.

Translated by Ian McGarry Translation & Language Services.

How to cite this article

Peter Tepe (2022): Roland Regner: Transformations. w/k–Between Science & Art Journal. https://doi.org/10.55597/e8229

Be First to Comment