A conversation with Anna-Sophie Jürgens | Section: Interviews | Series: Street Art, Science and Engagement

Abstract: In this article, Graffiti and Street Artist PHIBS reflects on how public art in urban spaces can excite the public imagination about the history and cultural relevance of Street Art. PHIBS discusses his own artistic development and its embeddedness in the Australian Street Art scene, as well as the deep connection to nature and the urban environment that influences and inspires his artistic practice. Drawing on his experience of curating Street Art festivals, he explores the festival medium as a means of creating and communicating knowledge about the social role and meanings of public art.

PHIBS, it is absolutely wonderful to welcome you to the online journal w/k! Your website states:

“PHIBS is one of the most respected and renowned names in Australian Graffiti and Street Art. His public artworks are prolific in Melbourne and Sydney, as well as in many far-flung places across the globe.”

Your public art revolves around figurative work, abstract and organic shapes and letter styles, with animals and plants playing an important role in various forms and degrees of abstraction. Your work is placed in the permanent collections of the National Gallery of Australia, STRAAT Museum Amsterdam and IIT University in Mumbai. But you also curate Street Art festivals, such as the 2022 Surface Festival in Canberra, which excite and educate the public imagination about urban art and its fascinating history. All this is very interesting for w/k! In this article we invite you to reflect on your understanding of Graffiti and Street Art and how Street Art festivals not only inspire and shape your creative work, but also teach, transfer and create knowledge about art in public space. Our aim is to better understand the artistic concept behind your multifaceted work.

Hi! Great to be here.

PHIBS, in the online journal w/k, the word science – in line with the German understanding of the word Wissenschaft – includes not only the natural sciences, but any systematic knowledge-producing enterprise and research activity, that is, scientific and non-scientific inquiry, learning, knowledge, study and scholarship (see w/k in 5 Minutes). Given the “increasingly prevalent sense that science communication is not external to (popular) culture” ( Davies et al. 2019, 2), examining knowledge production and meaning making in culture allows us to identify formative cultural meanings that “may be the most important element contributing to public attitudes of science” (9). In the following, we would like to first explore your thoughts on urban art and activism and then discuss how the communicative role of Street Art can be captured in less tangible academic contexts and institutional settings, e.g. in the context of Street Art festivals (with educational panel discussions).

Graffiti: Urban Art, activism and excitement

PHIBS, how did you become a Graffiti artist?

Even before I picked up a spray can, I was always drawing and interested in cartoons, manga and comics. But when I moved to Sydney’s lower North Shore – I was 13 at the time – I saw all the Graffiti, literally everywhere, and I was immediately interested, curious, obsessed. Going to school, I started meeting other kids and people who were doing graff. (Graffiti attracts kids who are a little bit rough around the edges). I also eventually met influential older generation graff writers. I felt connected and started learning … Still growing up, I guess it was the risk taking and the adventure that was part of the appeal of doing graffiti. Spraying on moving carriages, for example, requires the ability and skill to create something in a short amount of time without getting busted. The fact that it would travel from one end of the city to the other and find an audience everywhere was exciting.

Back then – in the early 1980s – graffiti was a relatively new thing and not particularly appreciated by the general public. It hadn’t yet developed into the huge, multi-faceted subculture it is today. I guess the stuff we were doing was more based on what was happening in the US on the New York subways, which can be seen in books like Spraycan Art (by Henry Chalfant and James Prigoff) or Subway Art (by Martha Cooper and Henry Chalfant) – publications that were like bibles back then, and helped spread the subculture all over the world. But it wasn’t until I was mentored by a couple of older generation graffiti artists – mainly Prins and Dmote, who showed me how to do things and educated me about the scene and its code of conduct – that I started creating my own style and earned my rite of passage. I had all these other aliases/monikers that I played around with, but PHIBS remained. I liked it because it touched on Australian slang.

You create Street Art murals, but you are also a writer, as Graffiti artists call themselves. How would you define and describe Graffiti art / writing for our readers?

We Graffiti artists call ourselves writers. We write, we do pieces, we do tags (tagging is the act of writing your name or a special mark on buildings) – we have our own words that describe what we do, but graffiti is a term that the media gave the subculture and it stuck. At that particular point in time, in the 1980s, it was not really about making money or having a lucrative business. We didn’t care that the public didn’t know who we were or what we were doing. It was for the people who did it, mainly kids, but it wasn’t for anyone else – it was for the subculture, it was an in-house thing. Today that’s changed, because it has become a popular, sought-after culture and partly because social media gives you the opportunity to look at artwork all the time, everywhere. The amount of amazing artists that are out there is overwhelming.

Currently advertising has picked up an interest in it and likes to use it to promote their businesses, creating more opportunities for more people to do it. There are graphic designers, illustrators, tattooists and all kinds of other people having a go at presenting their artwork in this way. Public Street Art has become an industry in itself, attracting more artists and companies who are interested in throwing money at it. In many ways, Graffiti and Street Art have also become performance art; think of people like Banksy, who has taken it to another level by combining his projects with real showmanship.

Would you say the popularity has complicated Graffiti Art?

You now get these divisions in people’s opinions about what is worthy. Everyone involved in this subculture – everyone who takes it on or tries it out – has a different point of view on how it should be done, what is legitimate and what is not. A lot of the Graffiti artists tend to do it mainly because they like the illegitimacy of it, the illegal aspect; that it shouldn’t be done legally, that it was never meant to be … I’ve always been open to things changing. As I evolve, I get different interests and I move in different directions, but I acknowledge the roots and the true nature of straight-up Graffiti: the activism of going out and doing art without permission.

What influence do these historical roots and aesthetics have on your art?

I still do a little bit of cheeky stuff here and there. I enjoy that aspect of it. It’s a way of connecting with friends, it’s an act in itself. When you paint with other people, you share something. When we do words, we create something together. So it’s actually like a meeting of styles. People come together and have amazing adventures together. But there is also the other side. I had a lot of friends that I grew up with who got caught doing Graffiti a few too many times and then went to jail. Many, but not all, of these friends left graffiti behind and became more criminally minded.

What would you describe as the characteristic features of your Street Art and Graffiti?

My main symbols and characters are fish and birds. I developed a great appreciation for nature growing up in a small coastal town on the South Coast of New South Wales (an Australian state) and I was obsessed with David Attenborough from a very early age. As a kid, I thought it would be great to live underwater and I was fascinated by the other world in the ocean. But I also use the curl as a symbol, firstly to symbolise water (I am what you could call an ocean person) and secondly to represent a common pattern in and of nature itself – whether it’s referring to fractals, a curl in a shell or a fern (like how Maoris use it), the curl is new growth, a journey from one point to another, much like one’s life journey. I’ve never really been very interested in creating realistic artwork. My interest is more in abstraction and the possibility of seeing things in a new way.

Creating Street Art and Street Art knowledge through festivals

How did your interest in Street Art festivals develop? How would you define the Australian context?

After being a practicing artist for quite a long time in Sydney, I moved to Melbourne, which was very important for me because I started to make a name for myself there. I established a credibility and drew interest which led to more commissioned work. I started organising exhibitions and group shows and received invitations to international festivals. In this context, Australia is a little bit behind the time. In a way, that’s good for us because we have very unique, interesting things to offer here because we’re so far away from the rest of the world. But then when you look at what’s happening in Europe and the US, it’s amazing how big some of these festivals are. The public’s appreciation is also different because they’ve seen more of it and they’ve seen it change and transform – they’re a bit ahead of the curve and we’re still catching up.

The 2022 Surface Festival in Canberra was the largest Street Art festival you have curated to date. In the festival programme, you introduce Street Art as part of “the living infrastructure” of a city and as “outdoor galleries hung with reaction, rebellion and resonance of the world around us” (7). Besides art, what knowledge do you want to explore and share through the festival medium? And why are Street Art festivals important to have?

Street Art spaces in our cities are giant outdoor galleries with a whole other language to be explored. This is a secret language that only those in the know can interpret. However, Street Art – celebrated through festivals – stimulates and invigorates communities, by creating interesting areas that attract people, and encouraging them to spend money there (which is, of course, good for the economy). Street Art festivals – with artists creating live Street Art and graffiti artworks, as well as artist talks and panel discussions – is not only a great way to give back to the creative community, but also provides open opportunities to the up and coming. I really want the artists to meet and greet each other, to connect and find the people that they want to do more work with or learn from. Street Art festivals can also inform and educate city dwellers about the fact that, as I wrote in the programme you mentioned, Street Art tells the stories of the society in which it exists and is a multi-layered form of contemporary placemaking.

In our societies we’re conditioned to judge things as good and bad. As I mentioned before, graffiti was a term that was given to graffiti artists – writers – by the media, and it was deemed bad. But if you think about it – and these are things festival-goers can discuss with artists – if you have a lot of money or a business you can put up signs everywhere and bombard (if not brainwash) everyone with advertising, not just on TV but all over the city. This is considered OK. I’m pretty sure that advertising has influenced (or vice-a-versa) graffiti artists. Both advertising and graffiti are placed on the tops of buildings and on public transport. Like other forms of cultural expression (exhibited in museums, for example), Street Art and graffiti have a rich and fascinating tradition that teaches us a lot about how art undermines the power of commercialism and questions the social and economic infrastructure, as a fervent reaction to (if not rejection of) the status quo (in the 1970s/1980s). This is a story worth telling.

What at first sight seems complex and hard to read can really light up people’s world. Having colour around us changes our environment (so that it’s not repetitive advertising), but the festivals also show that Street Art is a powerful statement of community connection.

Strong Street Art can be beautiful and doesn’t necessarily have to have a message: it can be simply art for art’s sake. I also think it’s a great way to start a conversation and to make people think. In addition to aesthetic beauty, Street Art evokes emotional feelings and makes you think differently. Street Art is easy to digest; whether it’s an elderly person or a young child, they can look at a mural and understand something and take something away from it. Overall, festivals like the Surface Festival in Canberra represent a countercultural movement blossoming into mainstream appreciation and respect.

Would you agree that Street Art festivals offer a sort of informal education about public art – grassroots educational activism or grassroots art communication?

Yes, I would definitely say Street Art festivals open people’s minds about the importance of public art in our communities – how it can be used to beautify areas, create a destination that draws a crowd and in turn stimulates business/the economy. Most importantly it creates opportunities for artists and creatives. The Arts are often overlooked and not deemed particularly important in our societies. I’d say Street Art festivals embrace both educational activism and grassroots communication.

How have your festivals been received by the public/community, researchers and other artists?

Each event has been really positive. The communities appreciate and enjoy watching individual artist’s approaches and styles when creating something from start to finish, and the best thing is that once the event is over, the work remains, and still draws a crowd. It helps artists get exposure to a larger audience and hopefully boost their careers.

Festivals definitely draw interest from all walks of life and are mainly about celebrating something that people are passionate about, whether it is a viewer experiencing, or an artist participating in the event.

PHIBS, thank you for this wonderful conversation!

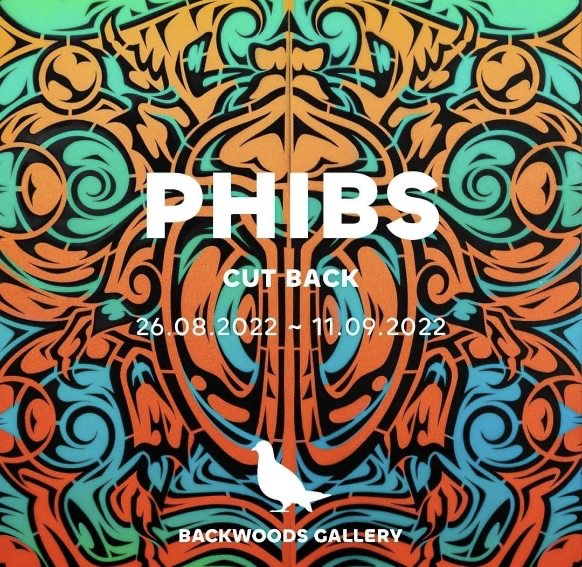

Details of the cover photo: PHIBS: Birds of a Feather (2013). Photo: PHIBS Archives.

How to cite this article

PHIBS and Anna-Sophie Jürgens (2022): PHIBS: Graffiti, Street Art and Engagement. w/k–Between Science & Art Journal. https://doi.org/10.55597/e8292

Be First to Comment