In conversation with Anna-Sophie Jürgens | Section: Interviews | Series: Street art, Science and Engagement

Abstract: In this article, Peter Bengtsen, who has written several books on street art, approaches the topic of Street Art, Science and Engagement as an academic. He discusses how he became interested in environmental street art, how his research developed and how and to what extent environmental street art can influence the viewer and bring about positive behavioural change. Unpacking selected international examples of public art, the article critically reflects on the power of street art to communicate environmental messages and raise public awareness of environmental issues.

Peter Bengtsen, it is a great delight to welcome you to our online journal w/k! You are an art historian and visual studies scholar – and Associate Professor at the Department of Arts and Cultural Sciences at Lund University, Sweden – with a background in sociology who researches and publishes on street art and graffiti. Your widely-cited publications include numerous case studies of street art projects in which you analyse the artistic concepts behind environmental art in public spaces and street art activism. All of this is extremely interesting for w/k, and in this article, we would like to invite you to share your thoughts on selected artistic concepts and how they engage with environmental themes, with the aim of better understanding the power of street art to convey environmental messages, increase environmental awareness and excite the public imagination about environmental protection and action.

Hello. Thank you for that introduction and your interest in my work. It is great to be here.

Peter, how did you become interested in environmental issues in street art (among many other things) and what are you currently working on?

Given ongoing issues like unsustainable consumption, pollution and climate change, it is not surprising that artists – including those that choose to place or create their work in the street – would feel the need to comment on the state of affairs. My interest in environmentally-themed street art arose from seeing an increasing number of such works and wondering how, and to what extent, they could impact viewers and change behaviours.

I published Street Art and the Environment in the summer of 2018, so about five years ago. Since then, I have been working on a different project related to graffiti and graffiti writing. Interest in my book and the research on environmentally-themed street art has risen in the past year or so. I think this renewed interest speaks to the increasingly tangible effects of climate change and other environmental issues around the world.

What does the work of an academic studying street art look like? How do you study and collect street art examples that address environmental issues (for example, the case studies you discuss in your 2018 book Street Art and the Environment, or examples from your current projects)?

For my first book, The Street Art World (2014), much of the research took place online – especially on forums dedicated to discussing street art and urban art. These were not set terms back then, and there still isn’t a consensus on what they really mean (e.g. does street art include curated murals? I would say no, but others might take a different position). Indeed, a central point of my first book is that the meaning of the term street art is socially constructed and constantly changing through its concrete, everyday use by members of the street art world. In addition to the online forums, where street art aficionados and urban art collectors would have discussions, I also collected material from street art blogs, the streets of different cities and from direct contact with artists and other members of the street art world.

After the publication of The Street Art World, the forums I had frequented during my research have either closed down or become increasingly focused on buying and selling urban art products, rather than discussing actual street art. Also, social media had by 2014 emerged as a fruitful resource for learning about new artists and artworks. For the second book, Street Art and the Environment, Instagram came to play an important role in collecting empirical material.

I have recently wrapped up a research project focused on methodological questions related to studying graffiti and graffiti writing through visual research methods. In the resulting book, Tracks and Traces (2023), I am specifically looking at the world of graffiti writing in Malmö, Sweden, which is the city I live in. Here, more than ever, the empirical material has been encountered in person on the street, the train yards and other out-of-the-way places in the city. However, social media again plays a central role in discovering work by local writers (as graffiti writers are often called), disseminating my own visual recordings (photos and videos) and engaging with other members of the graffiti world.

Do you collaborate with artists?

Up until very recently, I have not really collaborated with artists as such. However, since 2022, I am working on a project with the American artists John Fekner and Brad Downey. Fekner is an early pioneer of street art, having created stencil works in urban public space since the 1970s. Downey belongs to a younger generation of artists working in the urban environment (and beyond), and he creates incredibly playful and interesting interventions. Working with these artists is very exciting and a lot of fun. However, since the project is ongoing and still finding its form, I do not want to say too much about it just yet. What I can say is that the plan is to publish a small book in relation to the project – most likely in early 2024 – so maybe keep an eye out for that.

Given the myriad of fascinating street art projects, styles and mediums, how do you decide which artistic concepts to focus on – and why is it important to study street art in the first place?

As you say, there are so many things happening all the time. There is no way to cover it all. So, in the end, I suppose it really comes down to selecting things that I find particularly interesting, engaging, surprising and/or problematic. And to then find other cases that speak to the one(s) already chosen, until I have an argument I think is worth putting forward. As I write in my first book, I am not trying to say everything, but rather to say some things about street art and the street art world.

As for the importance of studying street art, I think art that is encountered in the everyday environment has the potential to impact viewers in a different way than art experienced in the white cube of a gallery or museum. And I think it is interesting to explore those differences. Of special interest to me is how street art can inspire and encourage people to take ownership of their local environs.

Street Art for Change?!

In Street Art and the Environment (2018) you examine a number of exciting environmentally-oriented street art projects. Could you introduce our readers to three of these (or other) street art projects and their artistic concepts that you find particularly interesting?

The first case in Street Art and the Environment is an example of clean/reverse graffiti by Alexandre Orion. In this work, rather than applying paint, Orion went into the Max Feffer traffic tunnel in São Paulo, Brazil and, using pieces of cloth, he began to selectively clean exhaust residue from the walls. In doing so, he created groupings of skulls that visually referenced the contents of an ossuary (a place or container for storing bones). This work called attention to the air pollution of our urban spaces in an interesting way.

Another case early in the book is the 1977 intervention A tribute to the green life that valiantly grows through this asphalt by John Fekner. It had multiple components, including a stencil painting of the title on the tarmac of the football/softball field in Gorman Park in Jackson Heights, New York City. This early environmentally-oriented street art intervention calls attention to the existence and perseverance of plant life in the urban environment, including in areas that have been designated by humans to serve specific other purposes.

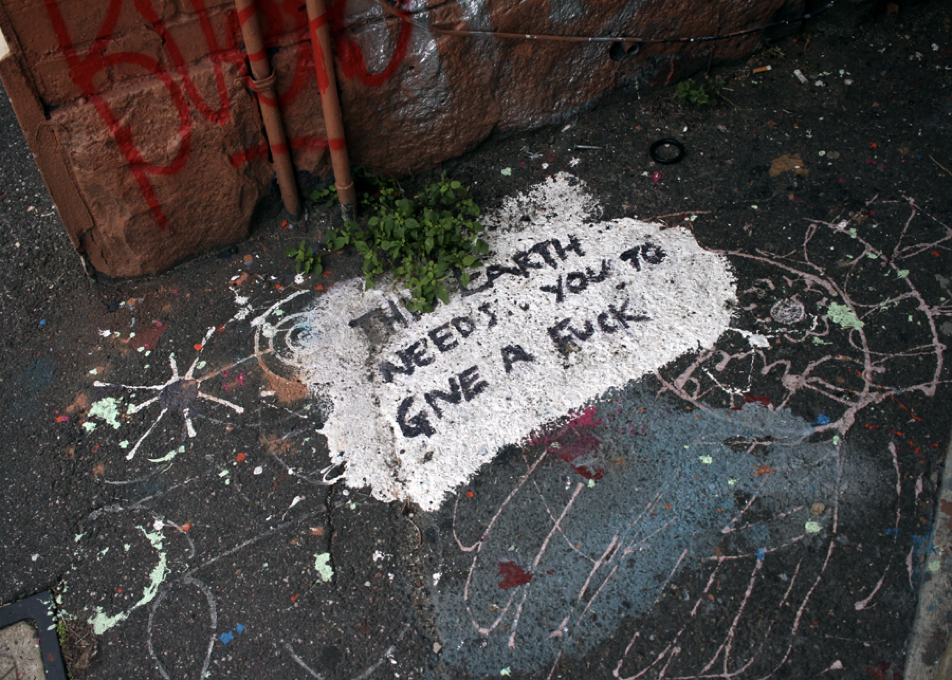

Finally, here is a work that is not in the book, but that exemplifies the plethora of minor interventions in a variety of different media one can come across in the street. This is a message painted on a sidewalk in Melbourne, Australia, which simply reminds us that “The Earth needs you to give a fuck”. I think it is important to remember that works in the street do not need to be monumental or complex to have an effect. Smaller works can surprise us in our daily lives and in this way have the potential to change how we think and act. This is true not just in relation to environmental issues, but also – for example – in how we make use of public space.

Yes, the last example illustrates well what you say in your book:

“street art, in virtue of its unsanctioned, ephemeral and open nature, can turn public space into a site of exploration”

and that

“unanticipated encounters in public space with art that might soon be altered or gone can cause people to pay increased attention to their everyday surroundings. In so doing, they may begin to question how public space is being used and how they want it to be used” (2018, 2).

Why are these artistic concepts and projects effective ways to get people interested, if not engaged, in environmental issues, such as environmental fragility and protection?

It is difficult to say whether these and other environmentally-oriented artistic interventions really are effective ways of creating changes in thinking and behaviour. What I am arguing in Street Art and the Environment is that visual art has the potential to capture the imagination of viewers and create engagement in more subtle, but profound, ways than factual information and scientific projections of future scenarios (which have often been ignored). By also engaging people on an emotional, and perhaps intuitive, level, artworks can serve as an important supplement to more traditional efforts to inform the public about pressing environmental issues.

Does a special kind of knowledge emerge from these street art projects?

As mentioned above, I think art has a potential to communicate to the viewer in a more direct and engaging way than facts and figures. While facts are obviously important, the lack of appropriate action in relation to, for example, climate change data shows, I think, that other ways of communicating are needed.

I think all kinds of art have the potential to reach viewers in this way. However, I see street art as a particular agent of possible change. Since it is an integral part of the urban setting, street art can create surprising shifts in our perspective on that context and our practices within it. This may open a space for reflection and foster increased environmental awareness and changes in behaviour.

The Street and the Environment Beyond the Street

In your publications, you refer to the transformation that digital technologies have brought to street art and its reach and impact. You write:

“The online dissemination of images of street art has become increasingly important, as the potential audience is far larger than the number of people who experience artworks in situ.” (2018, 76)

Could you tell us a little more about how they influence both the artistic concepts and the environmental messages of street artists?

The street context contributes to the impact of the artworks I have studied. At the same time, spreading images of artworks through social media may be an effective and efficient way of promoting environmental awareness – in part because of the vast potential audience, and because of the extra verbal contextualisation that can be achieved through these media channels. However, it should be noted that social media applications are also full of other, distracting, content. This may reduce the impact of the artworks experienced on there. Being placed alongside, and perceptually at the same level as, for example make-up tutorials and prank videos, may undermine the impact of artworks (and other content) dealing with serious topics.

How is your academic engagement with street art received by street artists?

The artists I have engaged with have so far all been very helpful and positive about the research outcomes. One thing I would note is that the street art world is clearly becoming more professionalised. Up until around 2014 (when my first book was published), artists would usually deal directly with requests for information, images and reproduction permissions. While working on more recent projects, I have more frequently found that this communication is handled by third parties representing the artists. This may speak both to the success of some artists (who now have less time to deal with requests in person) and to the growing field of street art studies (and the likely rise in requests from scholars that this entails).

In which direction would you like to see street art develop?

I would like to see more art that engages on a practical level with environmental issues, rather than just making commentary. One example of this, which I discuss in Street Art and the Environment, is Ernest Zacharevic’s Splash and Burn campaign in Indonesia. To highlight the threat that monocultural agriculture poses to ecosystems, the project includes land art interventions that create by cutting down oil palms large-scale imagery that is visible from the air.

I would also like to end by saying that, sadly, I am less optimistic about our ability to mitigate climate change and other environmental issues than when I wrote Street Art and the Environment. Although I still believe that art has the potential to foster positive change in how we think about and act towards the planet we inhabit, I currently think the changes that are being made to our daily practices are too small and too slow to have the necessary impact. Further, when confronted with large-scale and wilful acts of environmental harm – like the destruction caused by Russia of the Kakhovka Dam in Ukraine in June 2023 and the ongoing threat Russia poses to the Zaporizhzhia Nuclear Power Station – I must question, on balance, how big a difference our individual actions really make. This is not to say that we should stop trying, of course, but clearly a more fundamental, societal and legislative shift needs to also take place, so that large-scale environmental destruction (whether wilful or otherwise) comes to have serious consequences for those responsible.

Many thanks for this thought-provoking conversation!

References

A/Professor Peter Bengtsen, Lund University, https://www.kultur.lu.se/en/person/PeterBengtsen/.

Bengtsen, P. (2014). The Street Art World. Lund: Almendros de Granada Press.

Bengtsen, P. (2018). Street Art and the Environment. Lund: Almendros de Granada Press.

Bengtsen, P. (2023). Tracks and Traces. Exploring the World of Graffiti Writing through Visual Methods. Lund: Almendros de Granada Press.

Bengtsen, P. (2013). Site Specificity and Street Art, in James Elkins et al. (eds.): Theorizing Visual Studies: Writing through the Discipline, New York/London: Routledge, 250–253.

Ross J. I., Bengtsen P., Lennon J., et al. (2017). In search of academic legitimacy: the current state of scholarship on graffiti and street art. The Social Science Journal 54/4: 411–419.

Zacharevic, Ernest: Splash and Burn. Online: http://www.splashandburn.org

Details of the cover photo: Anna-Sophie Jürgens: Bengtsen Book Cover Collage (2023). Photo: Anna-Sophie Jürgens.

How to cite this article

Peter Bengtsen and Anna-Sophie Jürgens (2023): Peter Bengtsen: Researching Street Art. w/k–Between Science & Art Journal. https://doi.org/10.55597/e9296

Be First to Comment