In conversation with Anna-Sophie Jürgens | Section: Interviews | Series: Street Art, Science and Engagement

Abstract: In this article, Negar Yazdi – an urban planner recently honoured as the 2022 Australian Capital Territory Young Planner of the Year with over nine years of experience in shaping cities across various countries – provides insights into the close relationship between city art and the research field and practice of Urban Planning and Design. Through the lens of urban planning and design, she explores the role of public art in making better cities, fostering community engagement and creating unique urban experiences. In her view, public art contributes to the identity, liveability and lovability of cities and serves as a landmark that enhances the city landscape and facilitates navigation. This article highlights the importance of integrating art into urban design to create not only functional but also enjoyable, vibrant, inclusive and culturally rich city spaces.

Negar, it is a great pleasure to welcome you to the online journal w/k! You are the ACT Young Planner of the Year – an expert of urban space. As an urban planner with more than nine years of experience in different countries, you study and shape cityscapes and urban environments with a special interest in developing child-friendly cities and cultivating a strong sense of place attachment. In this conversation, we would like to invite you to share your thoughts on what our Street Art, Science & Engagement series can learn from the research discipline and research-based practice of urban planning. More precisely, what can we learn about street art – or rather, more broadly, city art – through the lens of urban planning? Our aim is to better understand the power of art in public spaces, not only to impart knowledge, but also to get people excited about art. Many of the artists in this series emphasise that street art is an engaging vehicle of artistic expression that communicates important messages and raises awareness, for example, about the need to protect our natural environment and biodiversity. In this conversation we want to unpack how exactly public art in urban spaces can achieve this – to what extent public art is an engaging and a crucial part of city life and city vitality.

Great to be here.

Experiencing the City (and) Art

Negar, how would you describe the research field of Urban Planning?

Urban Planning is the science of understanding the relationship between people and the city. It focuses on how the spaces and places we inhabit influence our communities and behaviour. People live in the city and have different relationships and attachments to its various parts, with varying scales, such as their precinct, neighbourhood and house. Urban Planning is also the practice of turning empty spaces into meaningful and functional places. It’s about the art of designing and shaping cities to create vibrant and liveable communities. By understanding the difference between space and place, urban planner aim to create environments that people can connect with and enjoy.

To sum up, a city is more than just the place we live; it’s a complex web of homes, roads, facilities and green spaces. Urban Planning is the thoughtful process of organising all these elements to work seamlessly together, creating not only efficiency but also places that prioritise the well-being and needs of the people who call the city home. It’s about designing cities that are not just functional but also enjoyable and supportive for everyone.

Do urban planners study public art as part of their education and training? How did you become interested in public art and how did your interest develop?

For my Bachelor’s degree, I studied Urban Planning and Design before specialising in Urban Planning for my Master’s. During my undergraduate years, I actively engaged in urban design projects, with a unique focus on incorporating public art. I discovered that art is not just a separate element but an integral part of planning and design. It’s the artistic touch that breathes life into the numbers, turning plans into vibrant and meaningful designs. Without art, it’s not just planning; it’s just a collection of numbers with no real character or creativity. Also, throughout my undergraduate studies, I discovered my interest in people-oriented design and public participation. Public art, I found, serves as a valuable tool to establish a connection with the community, creating places that are not only visually appealing but are also shaped by the input and involvement of the people. It’s a key ingredient in crafting places that genuinely reflect and enhance the needs of the community, making them more vibrant and community oriented.

Public art has a magical way of bringing places to life, infusing them with vibrancy and character. Whether it’s parks, streets or squares, public art can find a home in various city spaces. When people interact with these artistic expressions, they establish a deeper connection with the place, feeling a sense of belonging. In the realm of urban projects and beyond, integrating public art doesn’t just add interest – it crafts environments that are both fascinating and meaningful for everyone.

What influence does your background in Urban Planning have on the way you look at public space and public art?

In Urban Planning and Design, making a place recognisable and memorable is key. A successful urban design leaves a lasting mark, becoming the topic of conversations and ingrained in people’s minds, making history. Art plays a crucial role in this – it’s the ingredient that helps cities become distinct and easily identifiable. It’s not just about buildings and roads; it’s about leaving a lasting impression that becomes a part of the city’s identity.

Kevin Lynch, in his book The Image of the City (1960), states that crafting cities for pleasure is a unique art, distinct from architecture, music or literature. While urban design can draw inspiration from these arts, it forges its own path. A skilful urban design is intricately linked to cultivating an audience that appreciates and cares. As both art and audience develop, our cities have the potential to be daily wellsprings of joy for countless people, blending beauty with considerate planning.

Lynch identifies five key elements – paths, edges, districts, nodes and landmarks – that contribute to people’s mental maps of cities. He emphasises the importance of legibility, coherence and visual clarity in urban design to enhance the overall experience of city dwellers. The book has been influential in urban planning and design contexts, shaping discussions on the significance of human experience in the built environment. Lynch identified landmarks as one of the five key elements contributing to individuals’ mental images of cities. In this context, bold and distinctive street art and public arts are powerful, memorable, and recognisable landmarks. These artistic expressions become reference points that orient people in the urban environment, fostering a sense of place and enhancing the legibility of the city. By contributing to the creation of distinctive and memorable images in the minds of city dwellers, street and public art not only enrich the aesthetic fabric of urban spaces but also play a crucial role in shaping the overall perception and navigation of the city.

Below is a graffiti found on an electrical box in front of the Westfield Belconnen shopping centre in Canberra, near a bus stop. In light of Kevin Lynch’s ideas on urban design, this distinctive street art example serves as a noteworthy landmark that contributes to individuals’ mental maps of the city. Thus, the unique and recognisable artwork not only adds artistic value to the urban environment but also becomes a point of reference, aiding in the orientation and navigation of those familiar with the area. In this way, street art like the graffiti near Westfield Belconnen becomes an integral part of the city’s visual identity, contributing to the legibility and memorable character of the urban landscape.

When I see public art, I always consider how it helps people and communities define their city or neighbourhood. Public art plays a significant role in helping individuals identify and remember their surroundings. If you were to ask people to draw a mental map, they would likely include streets and their homes, as well as prominent monuments or artworks that stick in their minds. Public art has the power to leave a lasting impression and serve as a symbol for a particular place or space. Street art, in many ways, is thus City art.

For instance, when I mention Garema Place (a central square in Canberra), you may immediately think of a magpie eating fries, because there is a famous sculpture in this square depicting such a scene. In urban planning, it’s crucial to understand how people remember a place, as a city is all about the sense of place and collective memories it evokes. When a place holds a special memory for you, it develops a personality, and you feel a sense of attachment and responsibility towards it.

How would you – an urban planner – define the role and relevance of public art in our city spaces?

As urban planners we have an essential role in making public spaces inclusive, vibrant and attractive. Public art plays a role in making places more interesting and identifiable. When we are talking about public art, it could be a graffiti, sculpture or even a colourfully designed bench – a piece of urban furniture. These elements can make the place more inviting and increase the citizen’s attachment to these places. For example, imagine a public space including an artistic space where you can hang out with friends, play with your child or just sit and read a book or even park your car. How could this place become memorable for you? I believe if you can experience different feelings like sadness, happiness, love and even anger in a place, the place will be memorable for you thanks to those feelings. If you feel happiness in a public place, you will always have an attachment to that place. In Canberra, such a memorable space is Tocumwal Lane, which is likely the city’s most well-known street art hotspot. Tocumwal Lane, currently a loading area for restaurants, is one of the most memorable and interesting spots in Canberra.

City Art, Place and Play

What makes public art on public surfaces an attractive means of improving city experience, or even city vitality?

People living in urban areas or working in city centres may spend a considerable amount of time in cities each day, commuting, working and engaging in recreational activities. So, what can we do to make this time not just routine but memorable and enjoyable? Public art on public surfaces improves cities in various ways. It adds beauty and cultural expression, making urban spaces more visually appealing and reflective of the community’s identity. Art installations serve as landmarks and gathering spots; they foster social interaction and community engagement. Additionally, public art attracts tourists and boosts local businesses, contributing to the city’s economic vitality. Public art also helps deter vandalism while providing educational opportunities and raising awareness on important issues. Overall, public art revitalises neglected areas, making cities more inviting and enjoyable for residents and visitors alike.

How does street art enable a deeper understanding of the urban environment?

Street art helps us understand cities better in two main ways: First, it reflects the local culture and challenges, showing us the community’s identity and issues. Second, it addresses current topics, making us think about urban complexities. Street art also shares personal stories, bringing empathy to city experiences and encouraging city pride. It offers diverse perspectives, expanding our horizons. Being accessible, it lets us engage directly with a place, which deepens our understanding of the city. Street art’s changing nature mirrors urban dynamics, making it a powerful way to explore and appreciate cities.

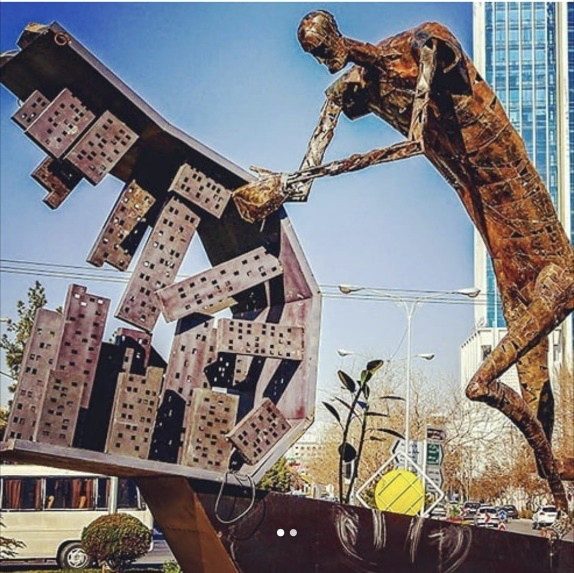

Public art isn’t just beautiful. It can be educational, sparking thoughtful reflection. Take, for instance, a monument in my hometown, Mashhad, Iran displayed in one of its squares. This piece of art visually communicates the impact of urban growth and unsustainable development, serving as a reminder of how these factors can harm the environment and plants. It’s a simple yet powerful way to convey important messages through art.

To come back to the term used above: in cities, public art is city art. City art is more than just design; it’s a powerful way to speak up about important things. It becomes a platform for sharing thoughts on what’s happening in our world, sparking conversations among the people who pass by. City art is like a friendly nudge, encouraging everyone to get involved and be part of the community. It’s not just about the artist; it’s about all of us, creating a vibrant and engaged neighbourhood together. City art, in its simple and colourful way, becomes a catalyst for change and togetherness.

Would you say that street art can be interpreted as a form of urban play? I know you are interested in the social role of play in urban environments, and it would be wonderful if you could share your thoughts on how play and art can possibly be seen together on urban surfaces and beyond.

Certainly! Street art can be seen as a form of urban play when it’s interactive and engaging. For instance, the famous piano stairs in Stokholm (Odenplan subway station) offer a unique blend of social, artistic and physical experience. The piano stairs are stairs that double as giant pianos. When people step on them, they make music, turning everyday walking into a playful musical experience. Stairs may not be as popular as they once were, with many people opting for the convenience of lifts or escalators in their daily movements. However, the piano stairs encourage people to choose the stairs when descending to the metro. This has several benefits:

- It promotes physical activity over using the lift or escalator, thus benefiting health.

- It adds an element of fun and gaming to the daily city journey, as individuals can create music while traversing the stairs.

- It encourages social connections among people using the stairs, as they can create music together as a team.

Such examples of street or city art become even more exciting when they’re interactive and engaging; this is a form of urban play. It’s as if the street itself comes to life, inviting everyone to join in the fun. Interactive street art adds a touch of magic to our daily surroundings, transforming the streets into interactive canvases waiting to be explored and enjoyed.

Negar, could you give us one or two examples of street art-meets-urban planning projects that illustrate some of your points?

Sure, an example are the concrete bus shelters of Canberra – beloved icons in Australia’s capital city. These structures have developed a special and lasting bond with the city’s residents over the years. They’ve grown to mean more than just places to wait for buses, as they now symbolise Canberra’s identity. People have found imaginative ways to interact with them, using them as artistic subjects and even incorporating their design into accessories like earrings and tattoos. Despite occasional discomfort due to their unique design, the bus shelters have become an integral part of the city, providing shelter, a sense of belonging and a hint of nostalgia for Canberra’s inhabitants.

Designing urban furniture as part of urban planning and design is one of the fields where art plays an important role. Being creative in this process can make a city more liveable and lovable. Urban furniture serves various functions such as providing seating or access to drinking water. By incorporating creativity and enhancing their aesthetics, urban furniture can become more functional and contribute to making the city more attractive.

If you could invent a science, what would it be?

Psychocity Science. Psychocity Science would be dedicated to the psychological aspects and dynamics within an urban environment. It would be the study or analysis of how psychological factors influence and interact with urban settings, including facets such as the mental well-being of city residents, the impact of city life on individual and collective psychology and the psychological implications of urban design, architecture and community interactions.

Thanks, Negar, for this very inspiring conversation!

References

Lynch, K. (1960). The image of the city. MIT Press.

Details of the cover photo: Mirrabei Dr Bridge along the Yarrabi Pond Walk, Gungahlin, Canberra (2024). Photo: Negar Yazdi.

How to cite this article

Negar Yazdi and Anna-Sophie Jürgens (2024): Negar Yazdi: City Art and Urban Planning . w/k–Between Science & Art Journal. https://doi.org/10.55597/e9504

Be First to Comment