A conversation with Peter Tepe | Section: Interviews

The first Part of the interview with Mischa Kuball has been published in the first issue of w/k. This is the second and last part.

Let us talk about a topic that is not directly related to science: light politics and media politics. To what extent do the different phases of your personal and professional development – the creative use of your individual situation, your psychology studies, your experiences in Gestalt Therapy or your artistic interest for neuroscience – imply a specific political commitment?

First of all, I would like to recall the saying that the private is political. It has a special meaning for me: if I started working with light and projection, this was also due to the fact that living in occupied houses I have never been able to fight the increasing capitalization of living space directly.

Where exactly were you involved in occupations and what was interesting for you in these contexts?

I participated several times, that’s right, for example in Düsseldorf, Berlin or elsewhere. Even today I find it inspiring to occupy spaces. As an artist, though, it is always an occupation upon invitation. My work generally reveals a certain tendency to infringement. Conventions and arrangements are in reality limiting spaces. Dealing with these limits also means developing a certain curiosity for what is beyond. When I was working in South Korea, people told me that I could go to Pyongyang in North Korea to realize a project there – I didn’t even hesitate for five seconds. In situations of this kind, I usually don’t think of possible dangers, but I try to find the best possibility to intervene.

So for you, art has to do with destroying standards and overcoming certain limits, including the limits of property.

In Leipzig, for instance, I projected something from an inhabited house onto an empty flat in the occupied house on the opposite side of the street, which was to be cleared by the police. Doing this, I was told that in another house there was a flat that its owners pretended to be inhabited although it was actually empty. So, I went into that occupied house and pointed a second projector on the house with the empty flat. Six weeks later, the flat was rented out, apparently because the owners had feared it to be occupied illegally. I usually deal with a specific situation establishing a temporary focus, some kind of essence or concentrate. For this, light serves as a marker, as a means of “enlightenment”, symbolically speaking. I occupy the space, I raise public attention and this leads to action. However, it is obvious that I won’t always be able to move things politically.

Do you consider these activities to be singular political actions that obey patterns like “I take offence at this vacant building and I would help it to be used again”? Or do your different actions merge into one and only political attitude?

I don’t have any manifest, nor a political program, not even in a rough or rudimentary form.

So it is a series of isolated political actions?

I had started to work like this in 1977. One day, Vanessa Joan Mueller asked me about the common denominator of these activities, or rather revealed to me that there really was one. This is why since 2009 I have – or better we have – gathered and compiled these works under the wider notion public preposition. In 2015, the Berlin-based publishing house Distanz released a bilingual publication entitled public preposition, which generally deals with the question of political action in art. Wanting to open up different perspectives on this kind of intervention, editor Vanessa Joan Müller from Kunsthalle Wien contacted authors like Barbara Steiner, Blair French and Zorn Eric. My contribution to this book basically consists of a longer debate between Vanessa Joan Mueller and me, in which we discuss the changing notion of the public sphere. The interview is entitled Öffentliche Beziehungen. The literal translation of this title, public relations, evokes totally different references if being used in German, as German people associate with this term above all the world marketing and advertising.

So, the different artistic actions rather are examples of how to overcome conventions – they are not grounded in a specific political alternative.

I do not appreciate the trend of putting artistic interventions in public space into a museum. This also includes actions that try to prevent certain institutions from shutting down. I have been concerned with activism since 1978. Back then, I didn’t know why I laid down on the street, I just thought it to be right. Today I know better what I am doing and why, so I know for instance why I protest against the closure of the library of the arts in Cologne or why I fight for maintaining the last public art gallery in the Bosnian town Bihac.

Let us talk about your project on Plato’s Allegory of the Cave. What did you do in this project?

It began with a rather accidental observation: The allegory in Plato’s Republic, that is the dialogue between Socrates and Glaucon, made me want to ask anew the questions of idea and thing, of image and copy. I thus started creating a series of apparatus in my studio, which remained unfinished. I showed them to people who had told me that they were interested in reading the dialogue again, and made them use these machines. Their experiences have then been put together into a very nice and – thanks to the great work of Christoph Keller – graphically appealing book called platon’s Spiegel. Zur Aktualität des Höhlengleichnisses – angeregt durch Projektionen von Mischa Kuball (Plato’s mirror. On the Actuality of the Allegory of the Cave – Inspired by Projections by Mischa Kuball), published by Walther König Cologne in 2012. For me it was very inspiring and challenging to work with authors like Hans Belting, Horst Bredekamp or Peter Sloterdijk. People like Yukiko Shikata from Tokyo, John C. Welchman from Los Angeles and Blair French from Sydney added their non-European point of view. And there were many more contributors, such as Peter Weibel, Ursula Frohne, Christian Katti, Duncan White from London, Leonhard Emmerling, Andreas Beitin, Wulf Herzogenrath, Martina Dobbe, Bazon Brock, Friedrich A. Kittler, Hans Ulrich Reck and Bernhard Waldenfels. Sorry, but I just had to enumerate all of them in order to illustrate how big this project actually was – making it come true was a monumental task for the three editors and the publishing house. The book also contains a conversation between Friedhelm Mennekes and me – which, by the way, made me feel quite uncomfortable in my role of a talking artist …

The text on your homepage seems to contain quite a few philosophical implications, for example your rejection of the thesis that reality is but a social construction. Are there any such references?

Yes, there are, and I actually talk a lot about them with others. I managed to bring together 20 authors from different philosophical backgrounds, geographical origins and cultures. My first question was: What happens in the Southern hemisphere (for example in New Zealand) to what the Western European culture considers its philosophical main reference?

Did you want to identify different culture-specific patterns of thought?

Absolutely, yes. I actually appreciate the approach of Roland Barthes – and anyway I sympathize with structuralism and poststructuralism: Barthes taught me that one can experience his or her own culture only through its being different from others. This was going to play an important role in New Pott – which we will talk about later – but it already had some impact on the Plato project. Discussing with 20 authors, I soon understood that one can reflect endlessly on this issue, the great variety of different intellectual approaches notwithstanding.

In my view, Plato’s Allegory of the Cave anticipates problems of media politics: For instance, the relation between an object and its shadow as well as our way of behaving to this relation are problems of media politics. This also raises questions about Plato’s understanding of the state as developed in the seventh book of the Republic.

I would like to know how you refer to certain elements of the philosophical tradition of thought and how you use them artistically. Plato’s Allegory of the Cave as a metaphor for Man being exposed to the influence of media – this seems to be the initial idea of your artistic action.

Yes, but I add insertions, inversions and so on. The platonic mirror, for instance, does not exist at all in Plato’s text, it is my own invention. I consciously chose to write platon’s mirror, which is grammatically wrong. I make mistakes on purpose because I want to maintain the impression of handling artefacts. I want to create mistrust through distortion.

If I got you right, your interpretation of Plato is a modernizing one. You do not try to understand the Allegory of the Cave in a historically adequate way, but to get something out of it which is relevant for us today. This is why you apply it to the modern constellation of a life constantly influenced by media and technology.

I answer as briefly as Glaucon does: That’s it.

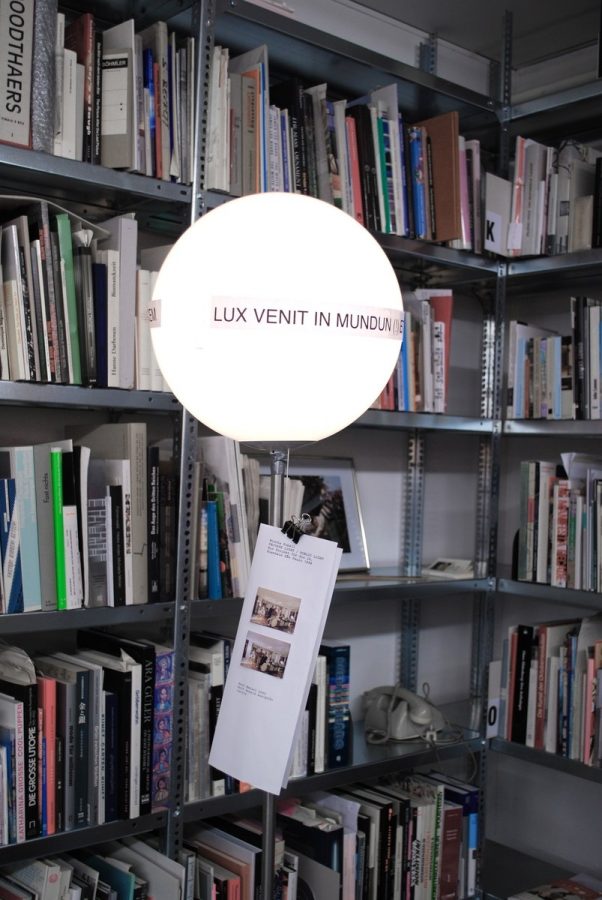

There is one aspect in your text that I find a bit irritating: the lux venit in mundum quote.

It is derived from the Gospel of John, but I use it in a figurative sense. While still busy with the Plato project I had already started with New Pott, transforming private talking into a stage through the use of light imagery. Providing talking people with a foreign body, a lamp that they had to set up in the place of their conversation, I literally managed to throw light on their private way of speaking. The reactions were very different. This was due to the fact that light is being interpreted differently in different cultures and religious backgrounds. All my earlier projects had an influence on New Pott and I consciously used those older experiences.

What was New Pott about?

The idea was born of my (so-called German) contribution to the 34th Sao Paolo Biennale in 1998 which was curated by Paulo Herkenhoff under the general theme of anthropophagy with reference to the homonym manifesto by Oswald de Audrade from 1927. This manifesto tried to give an answer to the European dominance in the domain of the arts, the Parisian art world pretending that Brazilian artists were copying European modernism. The manifesto replied: No, we will not copy, but guzzle and digest you!

My contribution for that Biennale was entitled private light / public light. Counting on the participation of 72 families, that is almost 500 participants on the whole, I took chosen lamps from their private environments and transferred them into the public space of the biennale with its 900.000 visitors. (You see, by the way, that my contribution had nothing to do with Germany or German art.) In all this, we made one mistake, though. Obviously, our participants told us a lot of stories linked to the objects they gave us and to their family lives, which we unfortunately missed to record. Only curator Karin Stempel, photographer Kelly Kellerhoff and I might still be able to remember them. That’s why for New Pott, I made it my basic principle to listen carefully to what our participants told us. Together with the photographer and film-maker Egbert Trogemann I recorded in word and image the stories of our 100 participating families, who came from 100 different countries. Thanks to the conceptual collaboration with Ruhr-University Bochum, we had access to a great network between Duisburg and Dortmund, Afghanistan and South Africa.

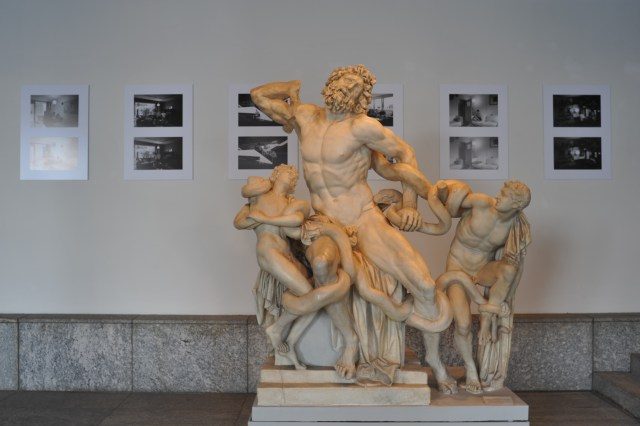

The Ruhr-University’s art collection and its curator Friederike Wappler gave us the opportunity to present the complexity of this project through different formats: as a multimedia video report, in a series of black and white photographs and last but not least in two publications, illustrated by Christoph Keller and published by JPR/Ringier Zurich.[1] Here, we focused on the personal and spontaneous conversations that the symbolical gift of the lamps had given rise to.

So, while for the Broca project and your adaptation of the Allegory of the Cave you used certain elements of science and philosophy, transforming them into artistic resources, the two to four hour talks with the 100 families for New Pott seem to obey a different pattern, namely the critique of sociological strategies. Interviewing migrant families is a recurrent issue of those social sciences that work with standardized interview techniques. By contrast, your general attitude seems to be: “This is not enough; I always have to accept the singular constellation of each of the families, I don’t ask them about specific things but rather let things happen.”

It is undoubtedly an artistic project, but as such it is not anti-scientific. I was interested in being a medium myself. Two aspects were invariable: There was always a lamp, and there was always me. Then we transcribed everything and read through the texts again, with the help of sociologist Harald Welzer. From the various heterogeneous encounters, he generated short and suggestive captions that allowed the viewer to experience the context and the connotations of each conversation. However, I definitely underestimated the complexity of this project. Another thing that we had not been able to anticipate were the consequences of the debate on and around Thilo Sarrazin. We underestimated the effects this debate would have had on our participants. When this debate ran high in the media, they somehow started to shut their doors. At first, they had all been very open and interested, but suddenly they started asking: “What is this conversation good for?”. Previously nobody would have cared about that. But let me come back to your question: I had not developed any meta-structure of questions in advance: every conversation took its own course.

So there was no general grid for the talks. You wanted to invite people to participate and then find out what the particular situation would tell you. You were trying to find the striking detail to base your work on and you did not want this detail to be hidden by a predefined pattern.

Exactly. However, one could argue that this detail would have been highlighted better if there had been a predefined and special technique of questioning.

Could you give an example for a conversation in which what you told us is particularly visible?

Mahamed Arouna comes from a small village in Niger. His goal was to play as a professional football player for a German football club – preferably for Borussia Dortmund. After leaving his country and arriving in Germany, he was put into a reception center. He had to submit a request for asylum and then waited eight years for the acceptance of his application, living in a 15 square meter flat. There is nothing wrong with waiting, but in this case, the problem is that waiting entails severe systemic consequences: Asylum seekers are not allowed to work nor to get out of a certain radius, they must not be seen at the train station, for example. And obviously, they are not allowed to play football in their favorite football club. This situation is highly political. Mahamed Arouna even brought his social assistant to the interview in order to avoid mistakes that would have created him even more problems.

I would like to tell you now something quite non-scientific: philosopher Bernhard Waldenfels and I were at a conference in Bochum which also Mahamed Arouna was officially allowed to attend. Waldenfels said to me: “This is not ok. You cannot force a person to speak without opening at the same time a certain space of action.” I replied: “Let me take care of it.” Mahamed Arouna appreciated my commitment. After having contacted several people, I negotiated with the officials in charge until we found a solution for the problem: Arouna had to leave the country, procure certain documents and enter the country again in a specific way – and now he actually plays football – even though not with Borussia Dortmund. If you wait eight years to become a professional football player you can lift as many weights as you want and hold up the ball at home, you will not make it anyway. My father was a professional football player, this is why I am quite familiar with this kind of thing. There is only a certain period of your life in which you can do things like this.

What I want to say is: The scientific ethos forces people never to look beyond their specialty. Whatever you do outside this field does not play any role in the scientific context, as your leaving your specialty could actually endanger the epistemic value of the scientific study.

Your research tries to overcome this rule. Talking to people, you try to find the “edge” that does not fit the scheme.

Yes, and to be honest, I eventually always find it.

Do you think that this strategy contradicts the scientific way of approaching a problem like the situation of migrants in Germany?

Yes.

Does that mean that your way of doing opens up certain possibilities which one usually does not have? It seems to me as if your project is based on this expectation: If you find this ‘edge’, you will have a key experience that you would otherwise been unable to access. Still, you could also try to reach this in a journalistic approach. Which leads me to the following question: What is specifically artistic about your project?

Right from the beginning of the whole project I have included artistic strategies. I decided to see the conversations in an anthropological light – just as August Sander did in his 14 year long photo project Antlitz der Zeit from 1929, in which he portrayed 600 people in their professional environment.

I wanted a structure which on the one hand gives in every single part an impression of the whole, on the other hand I enjoyed exploiting different means of expression: video documents, speaking in a space, silence in a space, the empty space. I also referred to the collection of the Lehmbruck museum choosing several stereotype representations of Man and his face. I wanted to open up perspectives. I actually avoid the common scientific methods of transfer. Transferring knowledge basically leads to exclusion and closure. Thus, I use conversation as a kind of prism which makes every project permeable for new elements and unexpected aspects.

The authors who participated in the project wrote their texts because they appreciated our discussion, not because they were keen on money: We continued our exchange and are now in a network which is built upon a certain thematic focus. In a scientific project, by contrast, you would have isolated one single element: You would have chosen a family, confront them with a predefined list of questions and repeat this about 100 times. My project on the contrary made people meet, the different families got into contact and started communicating among them – even those families who came from cultural backgrounds which usually tend to avoid one another. We thus created some kind of internal structure which does not emerge when working merely scientifically.

So your project is an artwork because of this network?

Yes. I have opened up a particular space of reference. I wanted to forget about all the different opinions and theories people tend to have on interculturalism, multiculturalism, transculturalism and so on in order to invite those who are usually being talked about to talk themselves.

The available time for our interview is up now. Thank you for the interesting talk.

[1] Harald Welzer/Mischa Kuball (Ed.): New Pott. Neue Heimat im Revier. Zurich 2011.

Friederike Wappler (Ed.): New Relations in Art and Society. Zurich 2012.

How to cite this article

Peter Tepe (2018): Mischa Kuball: Light Projects and New Pott. w/k–Between Science & Art Journal. https://doi.org/10.55597/e2549

Be First to Comment