Text: Jutta Wiens and Anne Hemkendreis | Section: Early Connections between Science and (Visual) Art

Abstract: Art and science are in constant dialogue in the work of Jean Painlevé, a French scientist and film-maker whose films are devoted to depicting underwater creatures in their aquatic environments. His 1928 movie The Octopus portrays a tentacular creature as a seductive protagonist that becomes an effective tool for scientific research and the dissemination of its results to a broader public. By inviting the viewers to participate in wonderous journeys into the ocean, the octopus functions as an epistemic object and fictional character alike. As this article shows, it is through the intermingling of entertaining effects – with scenes that negotiate the role of the octopus as an object of environmental study – that the question of how human beings can relate to nature in a non-hierarchical way arises.

Artistic Science Films

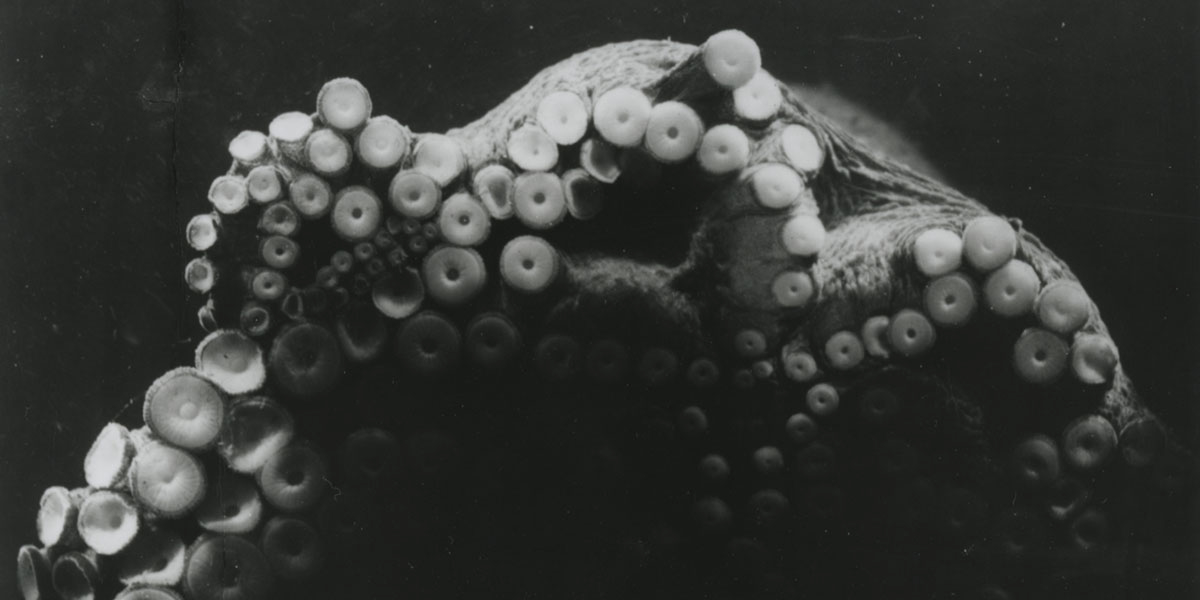

In Jean Painlevé’s (1902–1989) black-and-white film The Octopus (1928), viewers encounter a mesmerising aquatic animal in different settings while brief captions guide them through the visual scenes. The editing and cinematography create a dreamlike experience that links Painlevé’s films to the surrealist art movement, with its use of juxtapositions and symbolic tools. The viewers are further disrupted by watching mainly unknown and bizarre tentacular creatures. The audience is introduced and familiarised with the octopus through close-ups that show detailed visuals of its eye, the texture of its skin, and its suckers which explore the seemingly oceanic surroundings. The ability to change colour and shape, to move quickly and adapt to different environments is demonstrated in scenes on land, but even more so in underwater shots of the animal. The cinematography highlights the tentacles, which are portrayed as both delicate and powerful when used for moving, swimming and catching prey.

Painlevé’s biological expertise merged with his passion for the arts as he combined knowledge from comparative anatomy and the fluid aesthetics of early cinema. His films are works of art and early examples of popular science alike; they aim to create a sensual experience in which viewers share the feeling of an encounter with the invisible underwater life. In their seductive allure, Painlevé’s films create an impression of having stepped into an aquatic world. By seemingly penetrating the surface of the water and meeting the submarine creatures, the viewers become part of the close scientific observation of the octopus while simultaneously participating in the story of its life, which circles around the exploration of an underwater environment, the struggle to stay alive and the ultimate death of the animal.

Painlevé undertook a cinematographic operation, as in some scenes, fragments and parts of the octopus are enlarged. Through the focus on the eye and its humanlike shape, for example, the viewers recognise the similarities between themselves and the animal. This allows a process of reconstruction and identification where the animal is perceived as a related being. It also means that viewers become active agents in the reception process as the submarine unfolds before their eyes and within their imagination. The shift from the unfamiliar to the familiar has the power to evoke empathy for the octopus while also taking ontological differences into account; an effect that Painlevé strengthened in his later works. In this and his film The Love Life of the Octopus (1967) the voice-over and the text are used to raise awareness of the apparent strangeness of the octopus and its erratic behaviour while using language that reflects a human-centered point of view.

What is not shown, however, is Painlevé’s often violent treatment of the octopus; for example, forcing its eye to remain open. The purpose of the demonstration of newly acquired environmental knowledge thus came at a price – one that involved cruelty and captivity. The film was based on a hierarchy between humans as investigators and animals as objects. Feelings of familiarity – so-called entanglements – and practices of oppression create a field of tension in which Jean Painlevé’s artistic science films move. This article highlights the places where both attitudes towards the sea and its creatures become explicit in order to make general statements about a nature-human relationship in late nineteenth and early twentieth-century Europe and how it reflects our present.

Peculiar Environments

On 31 July 1858, the transatlantic cable enabling communication between England and the USA broke. When it was salvaged, scientists discovered that life could exist in the deepest layers of the ocean. These findings greatly increased the fascination with the submarine in literature and art. At the same time, experiments with aquariums became an integral part of both scientific and non-scientific culture in Europe in the late nineteenth century, as they were used as an epistemic tool to study submarine life. This was the beginning of the domestication of the sea that led to animals, like octopuses, becoming objects of research on aquatic habitats.

Painlevé was influenced by his studies at Sorbonne University (Paris) under Paul Wintrebert, who encouraged students to observe animals in unaltered environments. It was becoming increasingly clear that the Umwelt (environment) of the animal determined its development and behaviour, as biologist Jakob von Uexküll (1864–1944), for instance, pointed out. In Uexküll’s view, the body and the environment shape each other; the behaviour of the animal makes this relationship visible. This means that the environment provides cues for animal behaviour; it leads to the development of biosemiotics (the study of the production and interpretation of signs and codes in all living organisms) that actualise the peculiarities of animals. The octopus, for example, can create a habitat that suits its needs by manipulating objects with its tentacles or by releasing ink; it affects what happens around it. Consequently, environments are not stable but performative.

At the beginning of Painlevé’s film, the octopus is gradually introduced to the audience, which becomes aware of its alluring otherness and idiosyncrasies as well as familiar aspects that together result in an emotional involvement of the viewers with the animal and its story. The climax of the animal’s described adventures is reached when the octopus dies, beginning with a fight with another fellow species member and finally in the hands of a man. This scene shows the life of the animal as fragile: The octopus is not just a creature of fantasy or the otherworldly, but a real being, that – according to the narration – can wonder, feel and die. This realistic effect, however, becomes thwarted when the aquarium becomes visible, exposing the artificiality of the situation. At this moment, the feelings of immersion and fascination turn into an awareness of the artificiality of the filmed environment.

Painlevé positioned his camera so close in front of the aquarium that the frame was not part of the image, which creates an impression of witnessing the octopus in its natural biosphere; an almost perfect illusion. But if looked closely, some scenes show the octopus pressing against the glass. It seems to be agitated and looking for a way out of its cage; moments of realisation that change the atmosphere of the film fundamentally. Thus, although feelings of immediacy and connection are the first effects of the movies, they are juxtaposed by a glimpse into the artificiality of the environment, where the animal is shown to behave differently. Whenever the mediating function of the aquarium, and thus that of the film, becomes apparent, the otherness (the non-human character) of the octopus is made visible. It reveals that scientific research and demonstration are always based on manners of touch and penetration. As means to get a close-up of the animal’s tentacles, Painlevé indeed had to forcefully position the octopus inside the aquarium. Similarly, in order to relate to the octopus and enter its realm, the viewer’s gaze must pass through the aquarium glass; they become part of the scientific practice. The octopus, in the meantime, has no choice than to become an object of public disposal.

Image 2: Filmstill of “The Octopus” by Jean Painlevé, 1928.

In Painlevé’s film, the octopus is shown as an animal that needs a different environment from humans in order to survive and thrive. The fact that Painlevé – who carefully choses which scenes to include in his films and which to cut – decided to play creatively with the polarities of immersion/allure and distance/reflection suggests a meta-level of reflection on the complexity of human-nature relationships. The intermingling between science and art leads to a growing uncertainty regarding the question of what exactly the audience is investigating – an imaginary narrative or a scientific documentary. In fact, the space of the octopus in the aquarium is limited and its peculiarities become meaningless as the biosemiotics have changed. Applied to Painlevé’s ambitions as a scientist and a communicator of science, maybe this is a symbolic hint to the film’s own inability of conveying knowledge about untouched environments and natural behaviours of animals.

Non-human Entanglements

The otherness of sea animals was challenged when scientists began to promote the view that all life started from a body of water (for instance, Charles Darwin suggested this in a letter to Joseph Dalton Hooker in 1871). The new knowledge of human/nonhuman-relationships evoked a sense of kinship between the sea and life on land among scientists and laypeople alike, although it was also met with suspicion. On the other hand, the technological developments in the early twentieth century allowed new media, such as film, to explore techniques that alter the way the audience perceives and relates to the world. These include elements of storytelling that were used to evoke feelings of entanglements. The Octopus is an impressive example of popular science and marks a fusion of science and art. The film has the potential to promote a more sensitive ecological awareness that pays respect to non-human lifeforms, but also runs the risk of increasing attitudes of appropriation in science and aesthetics. The fluid lines between human and non-human invite the viewers to critically reflect on the interactions between the two but also to merely become entertained by the wonders of the submarine. Or in other words, the meta-aesthetic elements in Painlevé’s films are so hidden, that they might easily be overlooked. In addition, even if there is a critical approach on science practices to be found, the filmmaker still used them himself.

Painlevé’s films are thus both signs of a hierarchy between humankind and evocations of entanglements, as watching The Octopus leads to a blurring of boundaries between the human and animal spheres. This inseparability can also be seen in the anthropomorphisation of the animal as a human-like subject; this evokes feelings of empathy but also fails to respect the octopus as an entity in its own right. The feeling of emotional involvement is enhanced by the use of narrative subtitles and editing work to build a story and reflect the assumed inner world of the octopus – such as aggression or love – that result in an imagined bond between the octopus and the audience.

However, scenes in which the octopus orients itself become a central element of exploring sensory perceptions and their relevance for navigating this world. As Painlevé stresses, the octopus uses its tentacles to touch and navigate. Based on the knowledge of the relationship between sea creatures and humans, these scenes also point to the general importance of the physical engagement of living beings within their environments, including humankind. Painlevé’s emphasis on touch can be seen as a scientific and artistic approach to questioning how entities relate to one another through their bodies and within their specific surroundings. These elements of the film convey advanced scientific knowledge about the peculiarities of the animal, added by detailed descriptions of the octopus releasing ink.

The film asks about the similarities between human and animal perception and what special knowledge structures animals like the octopus can acquire through their specific anatomy. In this regard, The Octopus might also feature a type of ecological knowledge that is decidedly non-human and which invites feelings of curiosity and respect. Following this thesis, Painlevé’s film not only features hidden hierarchies in the relationship between humans and nature but also tentatively questions their justification.

Conclusion and Outlook

The Octopus is a powerful example and experiment in the field of popular science that shows attempts to demonstrate scientific knowledge through aesthetic means. Since German zoologist, naturalist and artist Ernst Haeckel (1834–1919), the role of art in communicating science has been to evoke feelings of wonder and connectedness that reach a wider audience than the description of mere scientific facts. Painlevé’s octopus must therefore be understood in a double sense: as a biological being that can provide insights into the specific behaviour of a marine life, while in a broader sense it functions as a symbol of an ecological concept that links humans, non-humans and their surroundings. Ecological philosophy in times of climate crisis points to this very idea of interspecies connectedness and asks what it might mean for a more respectful and less human-centred approach to nature when it is understood as a network of different human and non-human entities.

Painlevé’s films must therefore be associated with what has been called the non-human turn in contemporary environmental thought. Tentacled creatures such as jellyfish or octopuses are used in works of art to give concrete form to the idea of ecological networks and our mutual dependencies. This is also the reason why octopuses are increasingly popular in contemporary art, for example in Agnes Questionmark’s Transgenesis (2021). Given the persistence of exclusion and discrimination of the other, tentacled creatures in art are used as metaphors not only to negotiate the relationship between human and non-human, but also to question what being human actually means. The octopus as a character is fertile ground for further artistic experimentation as it has already become an inspiration for works of environmental art that seek to reimagine what it means to be human in a world that is changing dramatically. An analysis of the powers and dangers of Painlevé’s films therefore promotes a meaningful approach to the aesthetic communication of science: It enables us to learn and rethink how to visualise humans’ connection to nature and unthink ourselves.

References

Rugoff, Ralph: Fluid Mechanics. In: Science is Fiction: The Films of Jean Painlevé. Bellows, A. M. et al. Cambridge, 2000, pp. 48-57, here 49–50.

Hayward, Eva S.: Enfolded Vision: Refracting the Love Life of the Octopus. In: Octopus: A Visual Studies Journalopus, volume 1: fall 2005, pp. 29–44, here 38.

Cahill, James Leo: Zoological Surrealism: The Nonhuman Cinema of Jean Painlevé, Minneapolis, 2019, 71.

Harter, Ursula: Aquaria in Kunst, Literatur und Wissenschaft, Heidelberg, 2014.

Vennen, Mareike: Echte Forscher und Wahre Liebhaber – Der Blick ins Meer durch das Aquarium in 19. Jahrhundert. In: Weltmeere: Wissen und Wahrnehmung im langen 19. Jahrhundert. Winkler, M & Kraus, A (eds.), Göttingen, 2014, pp. 84–102, here 91.

Cahill, James Leo: 2019 (cp. fn. 3), here 42; Christina Helfin, Jean Painlevé’s Surrealism, Marine Life and Non-Ocular Modes of Sensing, in: CCSR Vol 2, No 3/4 2020, pp. 143–162, here 148.

Buchanan, Brett: Onto-Ethologies: The Animal Environments of Uexküll, Heidegger, Merleau-Ponty, and Deleuze, Albany, 2008, 2–3.

Exhibition Catalogue: Jean Painlevé: Feet in the Water, Jeu de Paume in Paris, 8 June to 18 September, 2022, 206.

Letter from Charles Darwin to Jospeh Dalton Hooker, Beckenham, Kent, England. 1st of February 1871, Darwin Correspondence Project, Letter no. 7471, accessed on 16 June 2023, https://www.darwinproject.ac.uk/letter/?docId=letters/DCP-LETT-7471.xml. See also: The Genesis Quest: The Geniuses and Eccentrics on a Journey to Uncover the Origin of Life on Earth (2020) by Michael Marshall and At The Water’s Edge: Fish With Fingers, Whales With Legs, And How Life Came Ashore But Then Went Back To The Sea (1998) by Carl Zimmer.

Latour, Bruno: Facing Gaia: Eight Lectures on the New Climatic Regime, Cambridge, 2017.

Details of the cover photo: Filmstill of The Octopus by Jean Painlevé (1928).

How to cite this article

Jutta Wiens and Anne Hemkendreis (2023): Jean Painlevé: Thinking with Tentacles. w/k–Between Science & Art Journal. https://doi.org/10.55597/e9198

Be First to Comment