A conversation with Anna-Sophie Jürgens | Section: Interviews

Abstract: Through their interactive art installations Aparna Rao and Søren Pors – the Bangalore-based art duo Pors & Rao – explore how life-suggesting animatronics can evoke the perception of complex inner states in inanimate objects. In this interview, Aparna Rao discusses her approach to technology, the nature of her many collaborations with technologists and her interest in combining high-tech and high-art.

Aparna Rao, I am delighted to welcome you to our online journal w/k. Together with Søren Pors, your collaborator since 2002, you create interactive art installations. Can you please introduce yourself and the Bangalore-based art duo Pors & Rao to the readers of our journal with my first question: What triggered your interest in the combination of high-art and high-tech?

Our starting point is always an idea. Usually a brief glimpse of something in the mind’s eye, something that we cannot forget about for some reason. About 15 years ago one of these glimpses happened to involve mechanical motion which meant that we had to work with engineers to realise it. Around the same time, an art gallery contacted us to show some early works, and that was how we started showing work in the art scene.

How has this interest in mechanical movement and the interaction of art and technology developed since then? And what kind of technology interests you most from an artistic perspective?

Well, it is these ideas involving lifelike motion and responsive behaviours that turned out to be quite technologically complex to do, so this forced us into technological research and finding out what motors are silent, small, robust and have a wide range of motions, and how non-engineers like us could use them to design motion and behaviour algorithms. And this has since become the focus of a small lab at the Wyss Zurich (a joint accelerator of the University of Zurich (UZH) and Eidgenössische Technische Hochschule Zürich (ETHZ)), where we are trying to develop a platform and a series of tools for lifelike animatronics.

Please describe two or three of your (favourite) artworks to the readers of our journal.

These things keep changing but for me personally, making the work The Uncle Phone was a turning point in my life. For the first time, I thought I could capture a private phenomenon in the form of a simple object, which I felt contained the complexity I was attempting to resolve. Of course, other people’s art also influences me/us. I remember visiting the Tinguely Museum in 2003, and feeling so moved by this realm of free, personal imagination that I wished I could develop my own and exhibit there sometime. And then ten years later we were invited to show the work Nisse TV as part of a Metamatic-related show. My current favourite is a new work in progress we call Coffin Eyes, which refers back to that moment and the materialisation of it which was so painful to us; but also quite comic in many ways; with some perspective in between.

You are leading a project called PATHOS (Poetic Animatronics Through Hands-On Systems) exploring how life-suggesting animatronics can evoke the perception of complex inner states in inanimate objects. Nested within Wyss Zurich, the project is a cooperation with the ETHZ and the University of Zurich – between your art duo, engineers and computer scientists. What are you currently working on?

We are always working on many projects at the same time because these processes take years, but one thing we are focusing on finishing right now is a small canvas that walks around in a space in a kind of silly or slap-stick way. It makes its own decisions where to go, and like a dog you meet on the street, it seems to have a plan of going somewhere, an agency of some kind. The mechanism, which was developed by a student at ETH in Zurich, allowed us to freely animate the kind of walking expression we wanted, and this enabled this kind of goofy and innocent feel we wanted. We are also starting to share these tools with others.

You studied at the National Institute of Design (NID) in Ahmedabad, India, and later at the Interaction Design Institute in Italy. Now you are working with and directing collaborators from different disciplines and backgrounds. In what ways, and to what extent, did your studies prepare you for the role that you have today, and that you compared to the role of a movie director in one of your former interviews?

My final project in NID was developing a simulator for a light combat aircraft for the National Defence. I think this experience, because the working conditions were so difficult and the task so complicated, did prepare me somewhat for how gruelling working with technology can be, and what it is like to be dependent on engineers and other specialists. In India, things are often much more collective and group-oriented, whereas in Europe, people seem much more self-reliant. I tried to learn to program a bit while in Italy, but I realised that this was not where my focus should be. I like to stay laser-focused on the visual expression we are looking for, so I don’t get either lured in or bogged down by technological biases or problems. The director’s role allows me to zero in on a small technical detail, but also to zoom out and solve problems strategically. And since many works involve electronics, programming, robotics and manufacturing, it makes sense to rely on experts in these fields.

When you talk about your work and its development, you do not talk about creating it (as I did in my introduction), but about producing artwork (you use the word production).[1] Is this related to the fact that developing the stunning and cutting-edge technology hidden in your artwork is a slow and, as you have just described, often painful process? Can you describe the way you collaborate with technologists and engineers in more detail?

Probably because producing is more aspirational. In reality we often go through many iterations and refinements before something works; and iterations in technology are very expensive – also on our creative stamina, so we really wish that we could just produce the artwork in a more straight-forward way. But sometimes new works have sprung from failed ones, so it is very unpredictable — like in the work Heavy Hat that started out as a sort of bouncing column which failed and then later became an upside-down figure.

Another challenge of collaboration is that each engineer unconsciously makes work in his or her own image, so their solutions end up reflecting who they are. In the beginning, we thought the technical process would be very rational and empirical, but while working with many different engineers we discovered that the solution they suggest is highly subjective, so you try to cast the right engineer for the task. And then you get to know all these people quite well and their personalities and energies seep into everything, so this is both a privilege and a challenge to control. Only rarely have we tried to leave certain things undefined to see what the engineer will do, and maybe take it forward from there; but again, if we are too open in the process it will never finish. So in general, we try to be ultra-precise down to the millimetre and microsecond.

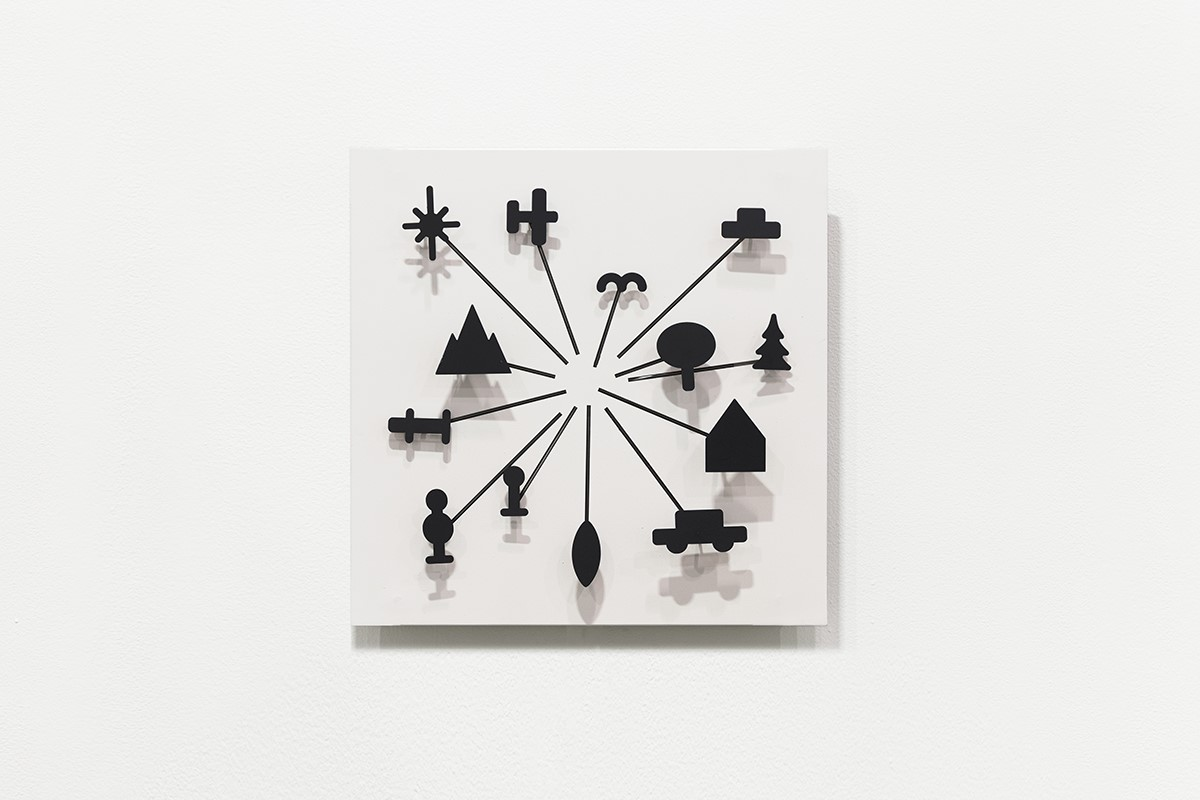

Before your first exhibition with Søren Pors in 2008/09, you spent several years thinking about what would be interesting for you. In this time you made a lot of small objects and drawings from which many of your later artworks seem to have emerged.[2] I am interested in the difference between working with your artist partner and with technologists. What are the crucial differences and synergies (in approach and perspective)?

Working with Søren is more like having a constant around to share a certain realm of ideas and thoughts and feelings, a kind of catalyst, friend and critic. This is quite an involuntary, organic state, so there is no effort involved really. In that way, I think what comes out is very relational. If I was working alone or with someone else, something very different would happen. At the same time, we are also strangers to each other, and this is nice because you can be close, but still have a lot of space for yourself. Working with technologists is a more practical relationship around a concrete engineering problem that needs to be solved, and since we work a lot with students, it does not last very long.

In what ways does technology act as a driver for novel artistic expressions?

We believe it should be the other way around. Artistic visions should act as a driver of technology. This is what we strive for. We are aware that many others use new technology to innovate visual language, but to us the danger is that the expression often tastes too much of technology, like a Photoshop filter with a tech-enabled aesthetic that ends up referring to technology rather than a subjective vision.

If artistic vision drives technology, what do you consider the contribution, or power, of your artwork in embracing, taming and enhancing our potential technology-related uncertainties and desires?

It may sound strange, but we are not interested in technology-related issues, other than our constant interest in trying to forget about it. The anxiety and geekiness around the technology is a pollutant we try to evade by hiding any sign of technological aesthetic, so we can just focus on the artwork. We are not impressed that some motors can move something or a sensor can sense something – this has been going on for a hundred years. Although, for our own sanity, we have developed an interest in how to make the technology robust so it is less capricious and fragile when in public display – so we don’t have to lie awake at night worrying about it. And as it turns out, this is incredibly challenging.

Talking about technological aesthetics … Some of your works are reminiscent of cultural phenomena in which the scenery becomes an active, dramatic agent. They remind me of the eidophusikon, for example – a kind of mechanical theatre and early form of movie making that created the illusion of moving nature without the use of actors. This theatre would employ mirrors and pulleys to reproduce the sights and sounds of shipwrecks or cities in flames. The diorama is another example. Developed in the early-19th century, dioramas provided theatrical experience that involved a three-dimensional full-size or miniature model of, typically, a historical event, landscape or cityscape. The eidophusikon and the diorama participate in the modern history of moving pictures, virtual realities and multi-media spectacle. These forms of entertainment established a notion of the cinematic that was not only ‘an ontology affixed to a new medium but always a new mode of perception linking spectacular vision and motion across modes of entertainment’.[3] How would you position your art in relation to such (historical) technological phenomena? Or, to what extent can your art be understood as a stage or theatrical vision of (virtual) kinesthesia?

It is probably related, but one of the things we were always after was the effects of life-like but also involuntary movement that occurs when the motion is very precise and hits some frequency band that is hardwired in the brain. This is probably an almost primal language of movement that we share with many other species and understand tacitly. There is also the nuance of how we do a certain motion; for example, how we put down a cup of coffee. There are infinite ways to do this, with nuances in the way it happens, which tell us something about the inner state of a being. This high resolution and specific focus is probably how the medium differs most from the mechanical dioramas which were bound to the aesthetic of the mechanical machine and its way of moving.

Of course, with microprocessors, there are the additional effects you get when using algorithmic functions like randomness and probability that, together with sensor input, can add unpredictability or organic feel to performative gestures. We like that the behaviour of a work is complex enough that it keeps surprising us, and this can be done fairly simply, but again, it all depends on the idea and the feeling we are after.

You recurrently – for instance in your TED Talks – refer to the artworks that you create as ‘creatures’ and ‘organisms’. You talk about ‘beings who seem to express themselves’, who have ‘ephemeral human qualities’, ‘as if sentient’. You create ‘autonomous’ ‘beings’ with an urge to get attention, which are unpredictable and, as you once said about Untitled, have their own personalities. To what extent does your artwork transfer human life into artifice?

It’s true that certain works played with this notion. The work Decoy is literally trying to get one’s attention by swaying and waving its arms – as if stranded or needing assistance somehow. In a way, all artworks want to be looked at, and so there is a competition for attention going on, and this becomes a bit comical.

We somehow like this notion that the artwork is alive – in a make-believe sort of way – and maybe this has to do with the physical motion or performance it can engage in; or the presence it creates in a space or how it speaks to the body. We are not really interested in a naturalistic illusion of life, but more as a sort of caricature of it, that we can play with stylistically. In the end, it all depends on what the idea requires, what it should trigger in us, and if it makes us project the exact emotion we desire onto the object. I don’t think we really understand this very well.

We do actually feel like robots most of the time, repeating the same thoughts, feelings and behaviours over and over. So in that sense, we do feel a strong affinity to some of our works that conceptually act in similar ways. There is something funny about human behaviour, in how predictable and robotic it is, as if we are almost completely scripted.

Non-verbal and pantomimic, primarily appealing through decorative, dance-like movement, your creatures do not mimic reality, they are autonomous visual characters. Do you think that they ‘puppetise’[4] the human form?

Well if so, it is not just the human form. Both Søren and I grew up with animals and we often felt much closer to them than the humans around us. Animals communicate a lot through their movements and they often have this innocence and purity about them which we really love. I think animals show us all the stages of sentience and consciousness, and in that sense show us something about ourselves, because we contain something from each of these stages too.

You mentioned that there is something funny about human behaviour (and maybe, if I don’t read too much into your answer, this applies to other animals too). And you talked above about the humour in your art. In what ways do your artworks express a comic vision of a technological world or of technology?

We find people’s behaviour quite funny and robot-like, but we don’t set out to comment on technology. People can read the work however they want, of course. We don’t see technology when we look at our things. I think it won’t be long before technology is only something to talk about if it is very new or bad. If it is good, it quickly becomes just another invisible extension of your daily life, like wearing glasses or shoes, and then you talk about what it enables, like reading a book or walking on sharp things. No one looks at a photo anymore and thinks of the technology behind the camera that captured it. People look at the photo and respond to what is on it, and this is what I think will happen to lifelike robotic motion eventually – or maybe even quite soon.

Finally, how would you describe, or sum up, the artistic goals you pursue in your work?

There are a lot of embarrassingly lofty ones, but mainly it’s just to make something really good. That will always be the hardest thing. Sometimes what makes something good instead of just OK is some tiny little adjustment or a random event that makes everything click, and suddenly this thing you’ve toiled with for years gets this amazing lightness to it, as if it is almost nothing and still very much something. In a way it feels alive, as if it has suddenly woken up and you have no idea what it is or why it is here.

Thank you for this wonderful interview!

[1] Artist Interview: Pors & Rao | Kochi-Muziris Biennale 2014, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=FZJnJCi2FFA.

[2] Artist Interview: Pors & Rao | Kochi-Muziris Biennale 2014, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=FZJnJCi2FFA.

[3] Rabinovitz L (2012): Electric Dreamland: Amusement Parks, Movies, and American Modernity. New York: Columbia University Press, 59.

[4] This is an expression borrowed from Taxidou, Olga (2005): Actor or Puppet: The Body in the Theatres of the Avant-Garde. In: Dietrich Scheunemann (ed.): Avant-Garde/Neo-Avant-Garde. Amsterdam/NY: Rodopi, 232.

How to cite this article

Anna-Sophie Jürgens (2020): It’s Alive! Aparna Rao on Bringing her Artworks to Life with Robotics. w/k–Between Science & Art Journal. https://doi.org/10.55597/e6371

Be First to Comment