Text: Irene Daum | Section: On ‚Art and Science‘

Summary: Psychological research has long been concerned with themes such as the perception of art, the process of artistic creation and the psychological basis of creativity. Art plays an important role in numerous fields such as clinical and applied psychology. Current research questions in neuropsychology are related to the mechanisms of art appreciation and the relationship between a work of art and the viewer in terms of an empathy-associated process.

Visual art has long been a topic of considerable interest in psychology, biology and related fields, with research issues addressing the perception and production of art, creativity and their applications in clinical psychology or advertising[1]. Apart from academic conferences and publications, these themes have recently also attracted the interest of authors of newsletters linked to the art world (e.g. news.artnet.com).

According to Darwin, “a taste for the beautiful” is already observed in prehuman species. It is characterized by a preference for regularity and harmony in form and the presentation of body ornaments which serve as a selection advantage. Play as a self-fulfilling activity is considered a precursor of art in animals, shaping perception and action control independent of the real world contexts[2]. The development of highly complex cultures in humans led to self-referential activities unrelated to the basic biological needs of life. In early human communities, high levels of energy, ressources and technical skill were invested in the use of ornaments to improve the appearance of objects. Growing tool use was linked to increasing appreciation of skill in execution and its training to perfection. Such interactions between the development of motor, cognitive and aesthetic skills presumably underlie the emerging appreciation of beautiful works of art[3].

What Makes Artists Special?

“Der Künstler ist kein Mensch. Er ist ein Künstler, das ist etwas anderes“ (Markus Lüpertz)[4]

According to the famous painter, sculptor, musician and poet Markus Lüpertz, an artist is different from other human beings. He/she leads a different life because of his/her given talent and his/her mission to create art[5]. Genetics, early support and encouragement by family and teachers and the intense pursuit of artistic production are thought to interact to form the conditions which are favorable to the development of artistic skill. Other determinants are personality, attitudes and self-image of the artist[6].

A family history of the pursuit of art has been reported for many famous artists, with the father and/or the mother being artists in the case of Albrecht Dürer, Pablo Picasso, Hans Holbein, Giovanni and Gentile Bellini, Paul Klee, Edvard Munch and many others. A passion for visual expression – drawing or painting – frequently emerged during the school years, together with more general evidence of outstanding talent such as a readiness of mind and fast apprehension (for details see [7]). According to recent research, the development of networks of the human brain is highly dependent upon experience, i.e. the continuous pursuit of specific activities and behaviours[8]. The strong commitment to artistic production in early years therefore appears to be an important determinant of the neuropsychological mechanisms underlying artistic skill.

There is a high proportion of left-handedness in painters; famous examples are Hans Holbein, Leonardo da Vinci, William Blake, Auguste Renoir or Caspar David Friedrich[9]. Left-handedness occurs in about 10-15 % of the general population and is linked to stronger involvement of the right hemisphere of the brain. The right hemisphere is associated with visuospatial processes, intuition and pictorial thinking, whereas the left hemisphere is more strongly associated with language and rational thinking[10]. Predominance of right hemisphere processing may facilitate the transfer of inner images into paintings or sculpture, serving as an advantage in the creative process.

Exceptional talent and creativity are frequently accompanied by an unusual “bohemian” life style, idiosyncratic thinking and an obsessive dedication to artistic creation as the basis of self-fulfilment. High levels of emotional disinhibition and risk taking may be common, together with narcissistic personality traits characterized by exaggerated feelings of self-importance, lack of empathy and interest for others and a high need for admiration by others.[11][12]

Psychological problems have strongly affected the lifes of many famous artists. Well-known examples are Michelangelo, William Blake, Wassily Kandinsky and Edvard Munch who all showed evidence of depression or contemporary artist Isa Genzken who suffers from bipolar disorder. Long-term alcohol abuse has been reported for Amedeo Modigliani, Henri Toulouse-Lautrec and Jackson Pollock, among many others. Addition to hard drugs such as heroin, e.g. in the case of Jean-Michel Basquiat, is also not uncommon. Among the causes and triggers for such problems are – apart from stressful life events such as loss of a partner – lack of recognition and success as a professional artist, self-doubt and unfavorable feedback by the public and peers which is being interpreted as disregard[13]. More recently, the demands of media fame and the pressures of life as a public person present challenges which may also be hard to cope with.

Neurological disorders affecting brain function are known to have a profound effect on artistic expression[14]. The paintings created by Willem DeKooning, for example, became more and more abstract during the course of dementia. Inner images are formed on the basis of perception, memory and general knowledge about the world. A breakdown of such stored visual knowledge might induce a freedom from inhibition in artistic expression leading to a new expressive style[15].

Life Experiences and Artistic Expression

As to the mechanisms underlying the creative process itself, artists have frequently reported a strong inner drive, a passion for artistic expression up to obsession. Joan Miro described the ongoing impact of sensory stimuli, a continuous flow of impressions and associations leading to insights into new meaningful relations and contexts[16]. According to Miro, a work of art represents a window to the inner world of the artist. The creative process starts in the brain/mind, moves to the arm and the paint brush and the canvas, with little room for conscious cognitive elaboration. Along similar lines, Georg Baselitz outlined how he abandons himself to the process of painting, a situation resembling a feeling of standing-beside-oneself[17]. The end result may even come as a surprise and according to Markus Lüpertz, you do not decide if a painting is finished – you know[18].

Decisive personal experiences are known to affect the work of an artist to a significant degree. Art does not only reflect such experiences and associated inner states, but also the process of coping with life events and trauma and a deep sense of understanding and insight. According to artist Hermann-Josef Kuhna, a painter paints the experience, not reality. A legendary example is the journey to Tunisia by fellow painters Paul Klee, August Macke and Louis Moilliet in 1914 which had a profound effect on their future work. Impressions, scenery and architecture led to watercolors and drawings displaying a new level of abstraction and the discovery of colour as a creative tool[19][20]. While travelling in the Sahara Desert in the 1950ies, ZERO artist Heinz Mack was deeply impressed by the archaic unspoilt landscape and vast space. His experiences formed the basis of a series of experiments with the effects of light on various materials, such as mirrors and silver. The placement of objects in the desert turned out to be an important ZERO project with lasting effects on Heinz Mack’s later work[21].

Fellow ZERO artist Günther Uecker has decribed a critical period towards the end of World War II when he was a teenager. To protect his family from the approaching Russian army, he secured the house by blocking windows and doors from the inside nailing up pieces of wood. Nails became integral to his work and his predominant medium of artistic expression, with designs and landscapes formed by nails emerging in paintings, objects and installations[22].

In addition to expression of personal life experiences in their work, artists often show a high sensibility for innovative ways of thinking in society, being able to foresee and understand the Zeitgeist and to participate in its manifestation. Well known examples of political engagement of artists are environmental themes elaborated by Joseph Beuys and H.A. Schult or the graffiti art of Harald Naegeli who sprays drawings on public buildings as a protest against inhuman living environments.

Art and Science

A detailed outline of artists with a background in science and of scientists with a strong interest in art is provided by Peter Tepe’s contribution Connections between science and (visual) art in this issue. Peter Tepe’s state-of-the-art review comprises six chapters, with the current w/k issue presenting the preface.

Traditionally, art and architecture/engineering were strongly linked. Leonardo da Vinci was obsessed with the assessment and understanding of proportions and fascinated by geometry, conducting experiments with melting processes during the construction of machines. The underlying idea was to learn from nature by detailed observation which ultimately enhanced visuospatial imagery and three-dimensional thinking as a result of long-standing experience.

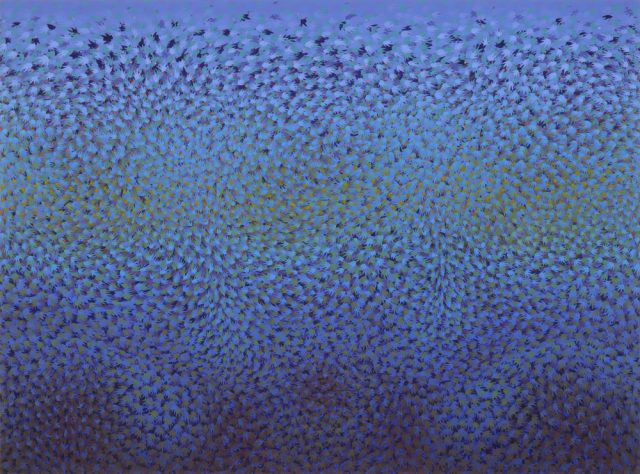

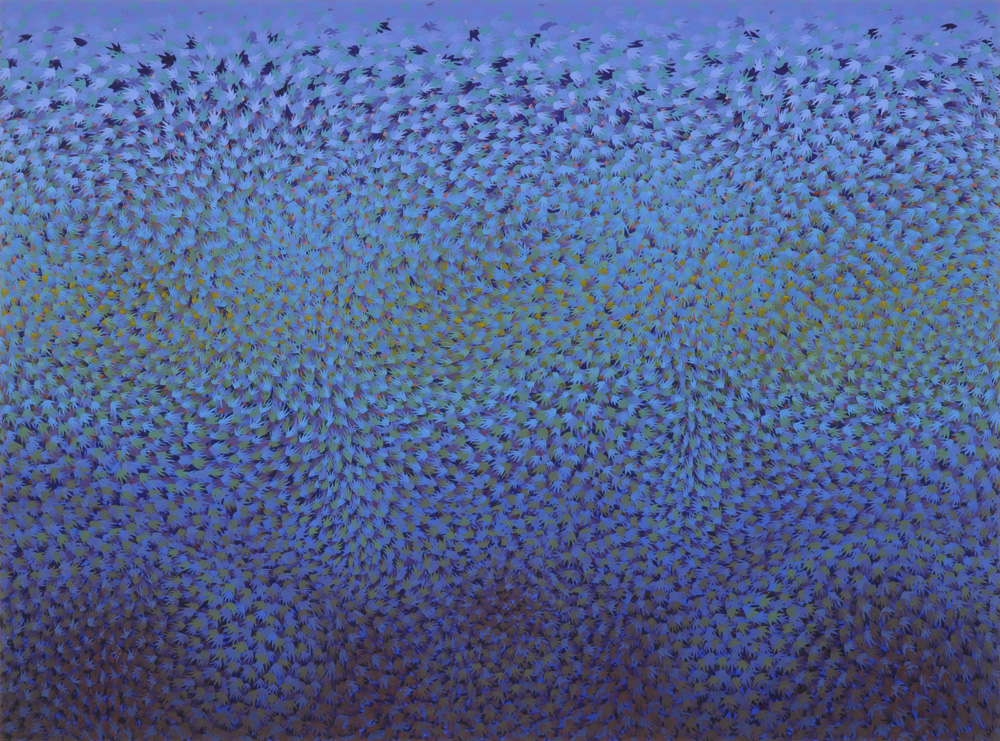

A background in science is known to affect the choice of motifs elaborated by an artist. A contemporary example is the work of Hugo Boguslawski who studied biology in addition to art before turning to full-time work as an artist. In his paintings, elements of nature – leaves, traces of small animals, etc. – are assembled and grouped into abstract composition, often in strong, non-naturalistic colours to form a type of new organic setting, going far beyond nature[23].

Another example of a biology-art link is the work of the Italian painter Silvia Stocchetto. She graduated in biology and even continued her scientific work to complete a doctorate in biology before abandoning science and turning to the study of art and painting in particular. Her compositions frequently combine single hyperrealistic elements taken from nature – animals, trees etc. – to create extraordinary novel wild life sceneries and modern-day still lifes.

After studies in the field of technology, Detlev van Ravenswaay (see also Detlev van Ravenswaay: Space Art. An artist interview) initially concentrated on realistic illustrations of astronomy and space technology themes based on precise scientific knowledge, leading to international Space Art fame. Later he turned to free art with his science background still entering his work, e.g. in a series of landscape-type images entitled “multi-horizons” in which he translates images of the earth atmosphere as seen from orbit into colourful abstract paintings[24].

The rising recognition of the role of art in relation to science is reflected by the introduction of “artist in residency” programmes in research centers of international standing, e.g. at the European Organization for Nuclear Research (CERN) in Geneva.

Perception and Appreciation of Art

The subjective response to art has many facets and may involve interest, joy and pleasure, but also anger and disgust. Responses are influenced by a range of variables including content, actual mood, experience with art, familiarity as well as fame and market values of the artist[25].

Features of visual information processing as determined by psychological research affect the viewer’s choice to a significant degree. The general preference of regularity, symmetry and compositional balance is linked to ease of perception, reduction of tension and an ideal activation level in terms of a “good gestalt”. The right balance between complexity/arousal and order, i.e. the right mix between the familiar and the unfamiliar is generally achieved by the use of strong contours, colour contrasts and the inclusion of elements of surprise. Interestingly, empirical research did not consistently yield a preference of composition arranged according to the golden ratio (for detailed analyses see[26]).

On average, figurative paintings are preferred to abstract paintings. The appreciation of abstract art does, however, rise with increasing exposure, supporting the assumption that experts view art based on cognitive models whereas non-experts are guided by familiarity and pleasure. This finding may be related to the two basic information processing modes: bottom-up processing reflects the processing of input by the visual system into shapes, colours and patterns whereas top-down processing of visual input is strongly driven by stored visual patterns and memories[27]. Shifts of gaze and attention to salient details form a coherent image. Works of old masters generally represent prototypical objects and an image of reality which corresponds to stored representations of forms. With rising exposure to novel unusual input in modern art, the visual system develops finer-grained levels of discrimination and new perceptual categories, enhancing the appreciation of previously unfamiliar input.

Perceptual psychology has left its mark on recent art work, a prominent example being visual illusions in the mathematically inspired work of the Dutch graphic artist M.C. Escher. His drawings of figures and structures are natural at first glance, but appear disturbing at a second glance since they violate stored representations. His impossible triangle, for example, looks possible at each individual corner, but impossible as a whole object. This effect is based on the constraints of the visual system which has a strong tendency to construct three-dimensional objects from two-dimensional visual input.

The painter Josef Albers made extensive use of the physiological effects of colours and their interactions. His famous series Homage to the Square explored chromatic interactions with planes of coloured squares nested within one another, which induces impressions of depth and spatial effects in addition to colour interaction effects. The colour grey, for example, presented next to the colour blue merges into the subjective impression of a single colour after extended viewing. Or the colour yellow may lose its vividness next to the colour white.

On the viewer’s side, the kind of art individuals are attracted to is influenced by personality traits. Extraversion has been linked to a preference for modern art and introversion to a preference for more traditional art. Neuroticism has been associated with a high level of aesthetic sensitivity (for a summary see [28]). Continued exposure to great art can lead to strong emotional involvement and in its extreme form, to a set of psychosomatic symptoms which include perceptual dysfunction, tachycardia, panic attacks and loss of consciousness, a condition referred to as “Stendhal syndrome”[29]. The basis of such extreme forms of cultural shock is, however, subject to controversial discussion in the scientific literature.

Art is known to have an immediate precognitive effect, evoking an intuitive sense of beauty. According to Joan Miro, great art works like a punch, with no need for mediation by thought. At a second glance, on conscious reflection, associations with personal experiences and memories are evoked and influence perception of a work of art. In addition, mind wandering, creative imagery and divergent thinking may arise as a consequence of engaging in art[30].

On a psychological level, appreciation of art has been described as an act of empathy, with the artist’s inner states and emotions being triggered in the perceiver, leading to some kind of mirroring, an internal simulation process. This idea is based on the assumption that inner states of the artist are expressed through a work of art via the choice of content, colour and form, e.g. by expressing joy in bright colours and regular shapes and negative emotions in dark colour and irregular shapes[31]. While this assumption may appear too simplistic, recent neuroscience research indicates that content depicted in a painting as e.g. a particular movement does activate brain centers responsible for movement in the viewer and expressions of pain activate pain centers in the brain of the viewer, thus supporting the idea of an empathic relationship between a work of art and the viewer[32].

Art in Applied Psychology

The preference and appreciation of beauty has been made use of in advertising, the media and many fields of communication. Products which are linked to art work in advertising campaigns receive more favorable consumer evaluations and promote attention to the product and ultimately consumption. The connotations of excellence and sophistication inherent to art generalize to the product. Such “art infusion effects” even work for non-luxury items[33].

Recently, art has also been discovered as a potential driving force in the fields of organizational psychology and business consultancy[34]. Being associated with innovation and the quest for unconventional solutions, reflection on art may transfer to a more general openness to new ideas in relation to business challenges such as change management. What may be taught by engagement in art is to question conditions which are taken for granted by concentrating on unusual views, by looking at situations from a different angle or by recognizing subtlety. Art teaches seeing in more senses than one and the appreciation of quality and mastery. Engagement in art may enhance imagery and creativity as well as coping with ambiguity and multidimensionality, thereby supporting the discovery of the diversity of options in many business situations. The inclusion of art in the work environment has been found to promote communication, to create a favorable atmosphere and generally lead to higher work satisfaction[35].

Art therapy refers to the therapeutic use of art within a professional relationship, with art serving as a diagnostic and interventional tool and a form of communication between the client/patient and the therapist. Art-based approaches have been applied within the context of a wide range of behavioral or mental health problems, among them are schizophrenia, depression, post-traumatic stress disorder and developmental disorders. Drawing and painting may serve as a form of symbolic speech, their products being of highly personal meaning reflecting experiences, emotions and inner images which might make a significant contribution to reevaluation[36]. The therapeutic benefits of art production during recovery from illness or in the process of coping with chronic health problems have been widely acknowledged. Apart from the training of motor function and visual imagery, engagement in the production of art is known to improve mood, cognitive and social skills and to enhance stress management[37].

Beyond practical applications and its function as a sign of social distinction and prestige, it should be emphasized that people simply love art. In line with Markus Lüpertz, its most important role is to help people to develop new insights, to become more tolerant, open and generous[38].

[1] Schuster, M. (2011) Wodurch Bilder wirken – Psychologie der Kunst. Dumont Bildverlag, Köln.

[2] Sarasin, P. & Sommer, M. (2010). Evolution. Ein interdisziplinäres Handbuch. J.B. Metzler, Stuttgart.

[3] Sarasin, P. & Sommer, M. (2010)

[4] Stock, O. & Schreiber, S. (2015) „Der Künstler ist kein Mensch“. Interview with Markus Lüpertz. www.handelsblatt.com, 4.10.2015

[5] Stock, O. & Schreiber, S. (2015)

[6] Lange-Eichbaum, W. & Kurth, W. (1985). Genie, Irrsinn und Ruhm. Die Maler und Bildhauer. Reinhardt Verlag, München, 7te revised edition by W. Ritter

[7] Lange-Eichbaum, W. & Kurth, W. (1985)

[8] Bellebaum, C., Thoma, P. & Daum, I. (2012). Neuropsychologie. VS Verlag, Wiesbaden

[9] Lange-Eichbaum, W. & Kurth, W. (1985)

[10] Bellebaum et al. (2012)

[11] Lange-Eichbaum, W. & Kurth, W. (1985)

[12] Viveros-Faune, C. (2015). Why the art world’s raging narcissism epidemic is killing art. News.artnet.com, December 1, 2015

[13] Cascone, S. (2016). New study reveals artists share common traits with psychopaths. news.artnet.com, April 26, 2016

[14] Bogousslavsky, J. & Hennerici, M.G. (2007). Neurological disorders in famous artists. Frontiers in Neurology and Neuroscience, Basel.

[15] Chatterjee, A. (2004) The neuropsychology of visual artistic production. Neuropsychologia, 42, 1568-1583

[16] Erben, W. (1988). Joan Miro. Mensch und Werk. Taschen Verlag, Köln.

[17] Baselitz, G. (2011). Gesammelte Schriften und Interviews. Edited by D. Gretenkort. Hirmer Verlag, München

[18] Stock, O. & Schreiber, S. (2015)

[19] Schuster, M. (2011)

[20] Lange-Eichbaum, W. & Kurth, W. (1985)

[21] see www.mack-kunst.com

[22] Tittel, C. (2015). Günther Uecker – mit Nägeln gegen die Russen. Interview www.welt.de 28.09.2015

[23] see www.hugo-boguslawski.com

[24] van Ravenswaay, D. & Daum, I. (2014). Detlev van Ravenswaay – To new horizons. Verlag Till Breckner, Düsseldorf

[25] Schuster, M. (2011)

[26] Schuster, M. (2011)

[27] Bellebaum et al. (2012)

[28] Schuster, M. (2011)

[29] Magherini, G. (1989) La Sindrome di Stendhal. Ponte delle Grazie, Florenz.

[30] Chatterjee, A. (2014). The aesthetic brain: How we evolved to desire beauty and enjoy art. Oxford University Press, Oxford.

[31] Schuster, M. (2011)

[32] Chatterjee, A. (2014)

[33] Hagtvedt, H. & Patrick, V.M. (2008). Art infusion: The influence of visual art on the perception and evaluation of consumer products. Journal of Marketing Research, 45, 379-389.

[34] Bockemühl, M. & Scheffold, T.K. (2007). Das Wie am Was. Beratung und Kunst. Frankfurter Allgemeine Buch.

[35] Bockemühl, M. & Scheffold, T.K. (2007)

[36] Schuster, M. (2011)

[37] Malchiodi, C.A. (2012). Handbook of art therapy. Second Edition. The Guilford Press, New York.

[38] Stock, O. & Schreiber, S. (2015)

How to cite this article

Irene Daum (2016): Irene Daum: Psychology and Art. w/k–Between Science & Art Journal. https://doi.org/10.55597/e1227

Be First to Comment