A conversation with Anna-Sophie Jürgens | Section: Interviews

Abstract: In the second part of his interview, Dr Ira Seidenstein – a professional clown performer and clown trainer, theatre maker and author living in Australia – shares his thoughts on the cultural and intermedial appeal of the clown character. He discusses the extent to which clowns engage with two worlds: that of science and that of fantasy. Referring to the historical avant-gardes and their relation to science and research, Seidenstein explains how, for him, both the art of clowning and science emerge from play and discovery.

Editorial Note

Although w/k primarily focuses on the links between fine arts and science, occasionally the journal also welcomes contributions about artists working at the interface of science and art, and about border crossers from other art forms. The interview series (Go back to part I) with Ira Seidenstein introduces an exciting example of the latter.

PART II – Clowns and Scientists

The braiding and interplay of scientists and clowns has a long and productive cultural tradition in different media: on stage, in literature, film, etc. In focusing on the popular stage only, what are your favourite clown-scientists or scientist-clowns – and why?

In terms of clowns and scientists perhaps my favourite may be from the Frankenstein movies I saw as a youth with Boris Karloff as the main actor. In fact, perhaps my first clown character was dressing as Frankenstein (the monster not the doctor) for Halloween which I did a few years in a row. I consider Frankenstein a clown because of his vulnerability combined with his unpredictability as well as his inexperience and confusion about love. Frankenstein’s discovery is his humanity. In a similar paradox that a clown’s mechanical aspects illuminate the human condition. There a few films of The Three Stooges, Abbott & Costello, and Jerry Lewis in which the clowns get involved with science which would also be amongst my favourites on the clown and scientists theme.

Talking about Frankenstein … “Mary Shelly will roll in her grave…” promises the webpage of Dr Frankenstein’s Traveling Freakshow (Tin Shed Theatre Company from the UK), a stage spectacle exploring where the monster has ended up after being brought to life: in a freakshow. A tribute to vaudeville, by staging sadist electroshock treatment, oversized slapstick and morbid fun, this “darkly comical and sickly twisted” show places George Levine’s idea that Frankenstein is “one of the great freaks of English literature” in the context of popular entertainment. Popular spectacle also provides the hotbed for another recent version of Shelley’s well-known recreational tale: the 2015 science-fantasy Hollywood film Victor Frankenstein, featuring a very intelligent doctor who is also a hunchback clown in whiteface, and becomes Victor’s assistant. If I remember correctly, you once mentioned that you performed as a ‘Frankenklown’. The monstrous wretch itself may thus take on the shape of the clown. How would you describe or position your interpretation of the Frankenstein theme within the Frankenstein tradition and the contemporary adaptions mentioned above that bring together popular spectacle (circus) and Shelley’s story about wild running science and technology?

I briefly headed a clown troupe called “Frankenklowns”. That came about in the following way: I was involved with a theatre group in Brisbane called Frank Theatre. Their use of the word ‘frank’ referred to being frank as in being earnest and honest as well as bold and brash. The method they used was from the Japanese director Suzuki Tadashi. The technique is bold and brash and extremely challenging physically. Five of the young female Frank members formed an offshoot called The Brides of Frank and they emulated images from The Bride of Frankenstein, The Addams Family, The Munsters. I started to create some clown theatre pieces with our common method and wanted to keep the connection of Frank Theatre, The Brides of Frank, Frankenklowns though I mixed my method with the Japanese technique. I was involved in all of that for six years. Two of the shows of Frankenklowns were Mo-Ments in which I played the great Australian clown “Mo”; and, Chaplin’s Eye in that I played “The Ghost of Chaplin” which was like a windup mechanical doll with a slight nod towards Frankenstein in that both were part mechanical and part human.

You choreographed over 200 comic sketches and slapstick acts. Did these involve scientist-characters? What is the major lesson or insight that a clown performer can gain from science?

One of my plays had a science theme within it. Actually two forms of science. One was quantum physics as related to cosmology, and, the other theme was psychology which may or may not be considered a science by some. This was a duet called Howard & The Doctor. Howard had a condition called agoraphobia. To help his condition he went to a psychologist once a week for one year. The play’s scenario is Howard’s last session. The psychologist is a woman. She has found over the year that Howard is the most interesting man that she knows. Thus the doctor always looked forward to her sessions with Howard. In this final session Howard explains the creation of the universe to the doctor. So we see that Howard may also be far along on the Aspergers spectrum. When the session is over the Doctor is released from her bond of professional distance – according to this piece of theatre – and is free finally – according to this piece of theatre – to ask Howard to go out socially for a coffee. Part of the story is a myth about taboos in Western and modern society of pastoral care being turned on its axis by the universal mystery of love and attraction.

“Physics and painting are concerned with the same problem, namely the nature of space” (Laporte1949, 244). For Howard to explain his theory he has to use an available easel with paper and felt pen. In doing so he also shows a talent for drawing. I have found abstract painting and absurd theatre to be reference points for my creative work, method, and teaching. The work of Klee, Kandinsky, Miró, Chagall (who perhaps has his own genre) are points of reference for my work. Klee, Kandinsky, Miró were affected by discoveries in physics. Shortly after Einstein’s major papers were published the Fratellini clowns created a clown entree inspired by Einstein. That was performed in Cirque Medrano in Paris and the sketch is recorded in the book Clown Scenes by Tristan Remy. In Paris in the early 1900s intellectuals regularly attended the circus and amongst those who regularly attended were Gertrude Stein and Alice B. Tolkas. There is a book about Stein that connects her ten years in science (psychology and medicine) to her creative approach as a writer. That book is Irresistible Dictations: Gertrude Stein and the Correlations Between Writing and Science by Steven Meyer.

In 2016 with my I.S.A.A.C. collective in Paris I created a show Cubist Clown Cavalcade which was inspired by Pre-Occupation Paris and in particular the soirees held by Stein and Tolkas who were the protagonists in our production. There were no scientists in our show. I don’t know if scientists attended the actual soirees. However, it seems given Stein’s background in neural medical research and the discoveries at the time in physics, and the concurrent development of Cubism and the abstract that science and art would have been part of the discussions of Stein’s Saturday soirees.

To pursue “knowledge per se”, to unlock “the secrets of the organism” and to act as an explorer “not of untrodden lands, perhaps, but of the mysteries of nature” – this is why the naturalist William Caldwell travels to Australia in Nicholas Drayson’s 2007 novel Love and the Platypus. This spirit of discovery characterises the literary protagonist as a scientist – such as many other fictional and non-fictional scientists. I wonder how this relates to the clown from your perspective: Does the clown represent, embody or stage a ‘spirit of discovery’?

I avoid romanticism about clowns because I see people seeking a lost civilisation that never existed. Clowns exist in most human collectives. I think play is related to discovery and discoveries in science. Notable discoveries seem to require a possession and fervour bordering on madness. Some scientists like some artists go over the border without a passport to return. A few weeks ago in Zagreb I created an exercise with a workshop participant in mind whose name is Dada. Dada is a very powerful looking woman, but she is also sensitive and aware. She is an opera singer and clown doctor. Dada’s Exercise has only one sentence “I’m just a delicate little flower”. The performer says the line perhaps 8 to 12 times. As they tell the audience who they are by saying only that one sentence the actor is to create an arch from being delicate to being extremely angry and furious to being delicate again through their exit. The actor has to live their life of discovery of not being believed. One of my teacher’s said his method was “the art of discovery”. Which meant he could teach many techniques but until the actor learns, for themselves, how to discover, they will otherwise be lost. Perhaps for years. We see this in clown. People arrive to workshops and trainings desperate to become a ‘clown’. But clown is within. Sure there are many techniques of mime, and dance, and skills such as juggling or acrobatics, but, those are tools for clowns. One has to discover clown. That discovery is within. “Clown is just under your nose” is one of my favourite sayings when I teach. Another is “I’m not the clown. You are.” Yes the clown could be viewed and discussed to “represent, embody or stage a ‘spirit of discovery’ “. Definitely. However what is the science of clowning? That is what my method offers. A scientific template that is at once an individual and collective laboratory to examine what is the shift in consciousness from person to clown? Can we observe it? The method I offer trains the eye, heart, intellect, and intuition of the observer and of the performer. It takes time. In my work I insist that the clown has to be in control of four articulations: body, space, time, space/time continuum (which implies discovering how to think as a clown). I see the body as a scientific instrument. The body which includes the body/mind is a tool and apparatus which one can refine endlessly. Yoga is mostly viewed as physical, yet, the great treatise on yoga discusses primarily the mind (citta). That is the Yoga Sutras of Patanjali. My preferred translation is Light on the Yoga Sutras of Patanjali by B.K.S. Iyengar (first published in 1966). The scientist represents the ‘spirit of the mind’. But the trick is or the difficulty is or the joy is that in clown, and, in particular in the studio, workshop, and rehearsal situations, one must be present and aware. If one can practice living awareness in those situations then doing so in public performance is simply a natural extension and further revelation. Lo and behold clown is always right there under your nose. Pay attention to details like a good scientist. Then, suddenly, through the body, the intuition, and the intellectual concentration all working together discoveries will, as they do in science, suddenly ‘just’ happen. The real challenge in clowning is to notice them when they happen. Each science has its own form of logic and working chronology and cosmology i.e. evolution of its particular field. In my science for clown the actor must continually be aware of the body in space and time. The actor must also be able to shape-shift in one second. They must be able to jump from total intensity in one way, let’s say as an example intensely hard and fast, then to suddenly shift to soft and slow, and then in another moment back to hard and fast. With no effort. The effort needs to be in ones concentration and awareness. The power one uses on a violin is different than on a tuba. The intensity though is the same. The power varies according to the instrument and the composer and the composition. For an actor and a clown their body is their instrument. It is via the body that they can develop their mind, intuition, spirit, imagination, and creativity. So, yes, but, for the clown the ‘spirit of discovery’ must be embodied, visual, and visceral. In a way the clown travels along a liminal path which at once separates and unifies the body and mind.

According to Jack Oliver’s Incomplete Guide to the Art of Discovery, the drive to explore new frontiers, to seek the non-questions, to rebel against the status quo, and to having a knack for seeing things in a different light are essential characteristics of scientists. This reminds me of the definition of the clown that you gave my students at the intensive course/workshop on Circus & Fiction (Friedrich–Alexander University Erlangen–Nürnberg, June 2018). How does your definition of and approach to the clown relate to the imaginary around the scientist in culture?

My definition of clown came about by default. Scientists often employ and rely upon their students and inexperienced assistants as well as their learned colleagues. The default of my definition came about because I listened in earnest to a student who sincerely wanted to know if I would define clown what would my definition be. You see early on in my experience in clown I observed that the more clearly a teacher defined clown the less likely the student could discover for them self what clown means. For decades I would not define clown even though I was teaching clown. I appreciate and enjoy all different types of clowns including those who do not call themselves clowns. To help a particular student one day I made a discovery by formulating a definition of clown that works for me and does not hamper the discovery by different people for their own interest in clown. “A clown does what s/he wants, when s/he wants, however s/he wants, for as long as s/he wants”. The scientist must work always with two opposite frames of mind. They must be solid and meticulous with the protocols of their field yet they must hold loosely to allow for spontaneous discoveries and realisations to occur or to be framed in a new way. Social theorist Pierre Bourdieu explains that in every field the culture is a continuous battle between orthodoxy (as things have been established and maintained) and heterodoxy (allowing for new ways and ideas to be integrated into the established protocol). It seems that every discovery in science must or has gone through a battle to be accepted. In the field of clown there seem to me a lot of assumptions which are dogmatic and ineffective.

Why do circus and clowns matter as cultural, literary, performance phenomena today?

Performance phenomena such as circus and clown in today’s culture and literature provide a sense of ritual. In literature it is as if we can look behind or inside the ritual. In the mainstream and commercial areas shows such as those from Cirque du Soleil and Slava’s Snowshow are aware of using ritual. The need and power of ritualised performance is also part of the plays of William Shakespeare. In all three (CDS, Snowshow, Shakespeare plays) the story is interwoven into the ritual, but, the story is secondary to the ritual. These shows are all communion as in a religious rite which is the origin of theatre. Perhaps the works of James Thierree could also be seen as ritualised drama more than just a story or a play. Clowns have always entertained in hospitals, but, it is only recently that clowning in hospitals has become commercial. None the less in that context, for example, the clown has the role of healer as bringer of joy, peace and solace. This generosity of spirit even occurs in the most commercial clowning which is birthday party clowns who each weekend perform in private homes in the major cities of some countries where they also bring joy, peace, and solace. So perhaps every clown has the potential to bring such qualities? It is said that clowns are meant to be funny. Is that true? Actually it is comedians that are funnier than clowns per se. Certainly some clowns are funny, but, usually it is the ritual of clowning that is funny. The mechanical structure is simply setup, repeat, surprise then the laughter occurs. Some of the greatest clowns are comedians who clown, such as, Jim Carey, Steve Martin, Woody Allen, Robin Williams, Joanna Lumley.

Finally, why should we all read your brand-new book?

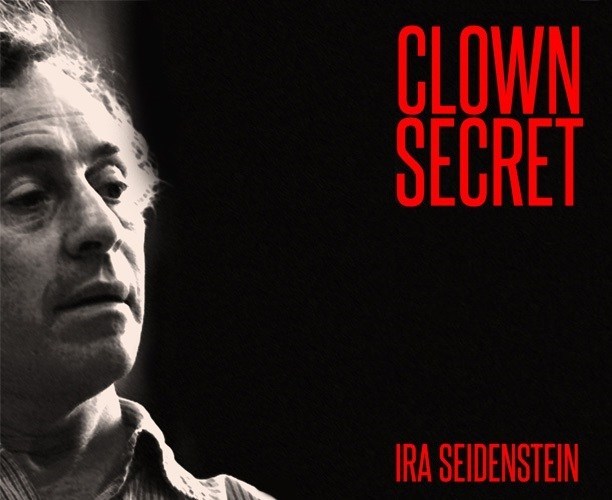

A good reason to read my book is that it reveals or shares some things about creativity that makes the book valuable to anybody. Another interesting aspect of the book is its unusual rhythm and writing. As is common with books from performers or artists it combines matters of life and art. One of the chapters is the whole introduction template to my method. There are step-by-step instructions. Anyone can learn them and anyone can benefit since the exercises are physical and creative. I propose that movement combined with creativity allows for health benefits to occur simply and naturally. In that chapter with the exercises I actually present the two most essential exercises first. I call them The Vitruvian Exercises as they were in part inspired from Leonardo da Vinci’s Vitruvius drawing. The Vitruvius drawing may be one of the greatest images of ‘science and art’ or ‘science, art, humanity and the cosmos’? In my book, which is called Clown Secret, I intertwine stories of making art, particularly making collaborative art. There is also a philosophical approach or questioning throughout the book. The many true stories throughout the book some people may find touching, or revealing, or funny. Most importantly I think people will find the book intellectually and creatively stimulating.

Thank you, Ira.

Picture above the text: Seidenstein, Ira: Clown Secret, Brisbane 2018, ISBN-13: 978-0648421603.

For further reading

Drayson, Nicholas (2008): Love and the Platypus, Carlton: Scribe Publications (quotes: 9, 59, 144).

Jügens, Anna-Sophie & Studenten (2018): Phänomen Manegenkünste, report (in German) of the intensive course “Zirkus & Fiktion” (Circus & Fiction, 7-9 June 2018), developed and taught for the MA programme Literary Studies: intermedial and intercultural), Friedrich-Alexander University Erlangen-Nürnberg, Germany: https://www.komparatistik.phil.fau.de/files/2018/05/Seminarbericht-Zirkus-Fiktion-final.pdf

Laporte, Paul M. (1949): “Cubism and Science”, The Journal of Aesthetics and Art Criticism 7/3, 243-256.

Oliver, Jack E. (1991): The incomplete Guide to the Art of Discovery, New York: Columbia University Press (quotes: 35, 37, 43).

Seidenstein, Ira and Mike Finch: In Hot Lethal Dangerous Ideas, Ira Seidenstein interviewed by Mike Finch from Circus Network Australia, https://www.iraseid.com/interview-withira.html.

Seidenstein, Ira: https://www.iraseid.com/ (personal webpage).

***

Watch out for Anna-Sophie’s forthcoming paper on parasites and clowns – written together with parasitologist Professor Alexander Maier. For more information see: https://researchers.anu.edu.au/researchers/jurgens-a

How to cite this article

Anna-Sophie Jürgens (2019): Ira Seidenstein: Clowning and Academia - Part II. w/k–Between Science & Art Journal. https://doi.org/10.55597/e4105

Be First to Comment