Text: Anne Hemkendreis | Section: Articles about Artists | Series: Ecological Art

Summary: In the aerial performance THAW, from Legs on the Wall Collective (2021), three heroines fight against the loss of their ice environment. Through de-humanisation and de-scaling, the performance suggests a post-anthropocentric worldview and makes complex scientific findings on the entanglements of ecosystems sensually accessible. By stressing the performers’ physical challenges and risks, the threat of climate change is mirrored and transformed into a bodily experience for the audience. Thus, THAW communicates scientific knowledge and fosters the necessity to act. This is highly relevant for w/k as it shows how science and research currently inspire and shape ecocritical performance art.

On 17 November 2021, an ice pyramid weighing over 2.7 tons floated point-down over the Sydney Harbour, with the Opera House in the background. Held in place by four massive steel cables and a crane, the ice sculpture swung over the water at varying heights. For over ten hours, three artists – Vicki van Hout, Viktoria Hunt and Isabelle Estrella – performed consecutively on the slippery ice stage, which increasingly melted under their feet. With their dancing, daring poses and gestures, the astonished audience saw the performers as three struggling heroines facing an invisible force. On the Legs on the Wall website, Joshua Thomson, the director of the piece, states:

“We are confronted by (the heroine’s) struggle and inspired by her determination to adapt and survive. THAW resonates for us all as we each grapple with our own role in the climate emergency and commit to our collective obligation to a sustainable future.”

The haunting effect of the performance was underlined, not only by the reference to the American Science Fiction horror Thaw, but also by the atmospheric music of composer Matthew Burtner, who took his inspiration from the scenery and sounds surrounding his log cabin in Alaska. This kinaesthetic effect, together with the physical challenges of the three women and their willingness to fight, holds a strong emotional potential for audience identification. It is heightened by the ice being a resistant, and yet sensually attractive, counterpart to the otherwise largely-isolated performers. Due to its decreasing material presence – its sublime luminosity and dynamism – the ice takes on the role of an active agent in the communication of climate change. By reducing climate change to the performance of an individual struggle, ice becomes a medium of knowledge transfer in the field of deep ecological thinking. This article aims to unravel the historic and current entanglements of arts and ecology dealing with arctic environments to better understand the artistic responses to scientific claims of environmental urgencies.

Since the heyday of the scientific expeditions to the North and South Poles in the 19th and 20th centuries, ice fields have functioned as a stage for the performance of heroic deeds, and have been inscribed in the cultural memory of the Western world. The great media response to the recent discovery of the sunken ship Endurance (2022) from the Shackleton expedition in the Antarctic and the media echo of the Mosaic Expedition (2019–2020) to the Arctic highlight the ongoing fascination with heroic polar travels. However, it is often forgotten that the narratives of an untouched, endless and dangerous ice desert as a testing ground for heroic polar figures bears a Western, colonial and masculine imprint. As Lisa Bloom puts it: “The difficulty of life in desolate and freezing regions provided the ideal mythic side where men could show themselves as heroes capable of superhuman feats” (Bloom 1993, 7). The conquest of ice as a more than human deed became powerful in the cultural imagination of the Western world because the mutability of ice made permanent possession, measurement and control impossible. Ice could not “be materially occupied in quite the same way as land, so symbolic enactments of claim and ownership carr(ied) a heavier burden” (Leane and Jabour 2020, 172). However, in the era of accelerating climate change, a redefinition of the relationship between humanity and nature replaces the need for testimonies of human superiority.

In the performance THAW, the melting ice is a sign of a world which is out of control. In contrast to previous imaginations of ice as a threatening force, the lack of control is now due to human influence – i.e. the male-dominated, mechanised and rationalised character of modern industrial nations. The performance poses a reassignment of cultural imaginaries and stresses the need for an increased connection with our environment. The melting ice – which evokes an irretrievable loss – becomes the testing ground for a temporary female performance that mirrors the changing nature of the ice. In doing so, the performance draws attention to the ignorance and exploitation of Western colonial history – which still determines our relationship to nature, especially the icy poles. Thus, the performance THAW uses ice as an active agent and uncertain stage which is re-occupied by female protagonists, while simultaneously refusing any permanent national or gendered appropriation.

Heroines on Ice: An Emotional Response to Environmental Urgency

The premiere of the performance THAW was characterised by a clear reference to place. The background view of the Sydney skyline, the harbour, bridges and passing sightseeing ships raised questions about the influence of mechanisation, economisation and tourism on nature. In addition, the proximity to the Opera House and Luna Park (since 1930) as places of modern amusement pointed to the historical roots of aerial shows and ice theatres, which originated from the entertainment culture of the 19th century. Being part of spectacular aesthetics, modern places of amusement served to celebrate scientific/technological achievements and functioned as testing grounds for visionary world views. As early as 1785, (artificial) ice appeared on stage in the London pantomime Omai, inspired by the North Polar voyages of colonial England (Leane 2013, 19). In Tasmania, the 1841 play South Polar Expedition celebrated the victory of science over the unpredictability of Antarctic ice and during the first actual Antarctic expedition of British Robert Falcon Scott, the crew even performed a play on “exile and homecoming” (22).

However, climate change has led to far more serious spectacles: in 2017 the giant iceberg Larsen C broke off from Antarctica. In addition, the devastating bushfires and the recent floods within Australia have fostered a change in environmental consciousness worldwide. Instead of controlling and harnessing nature through mechanisation and rationalisation, a sense has developed that “humanity had a hand in producing a monster entirely beyond its control” (Leane and Philpott 2020, 3). This Frankenstein effect of human civilisation – such as the rise in temperature and sea level – promotes awareness of an icy connectivity across all parts of the world. Today, environmental sciences stress that the interdependence of ecosystems not only points to the entangled nature of the past and present for humans, but also their future.

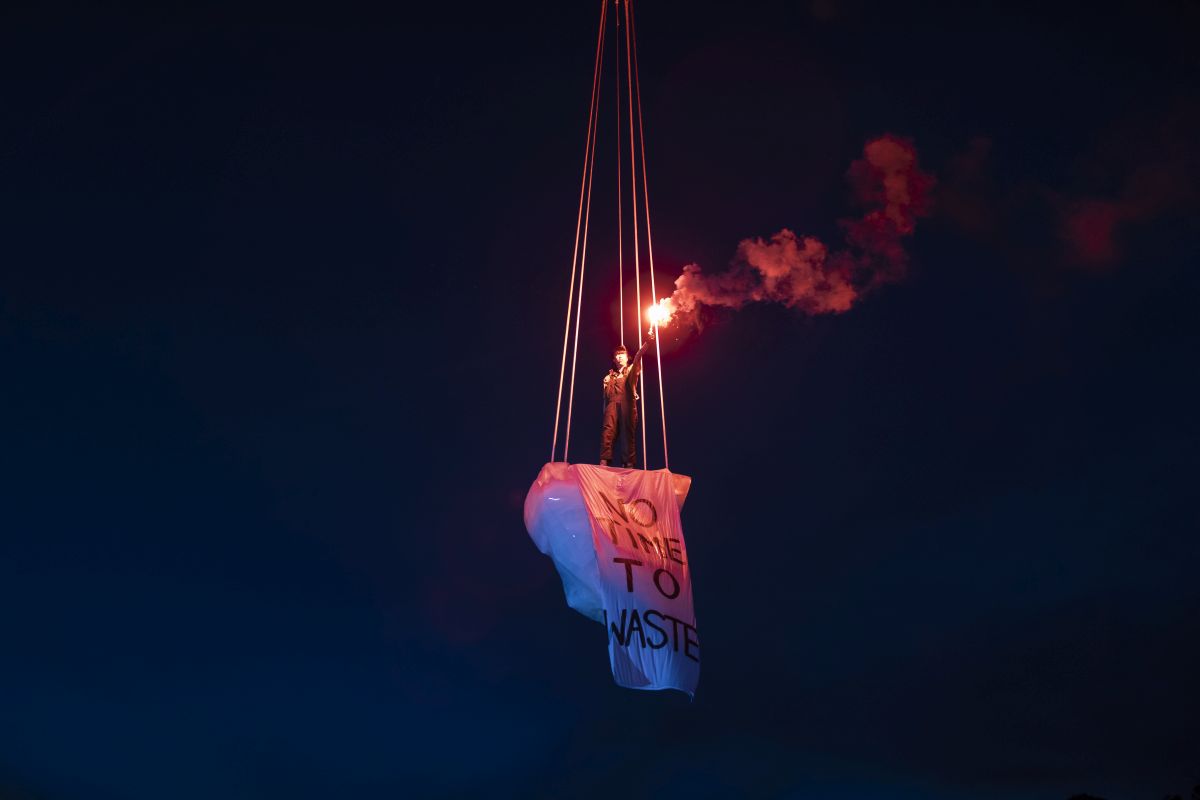

For the artistic communication of entangled futures, the mutability of ice is a unique tool for visualising the dramatic changes in the world, especially when ice is integrated as an artistic material. Due to its dynamic nature, ice makes the changes on our planet and the ecological responsibility of humans particularly clear. As an active medium, it emphasises the risk of global warming and presents the world not as something that merely exists, but as threatened with change. It is precisely these aspects that THAW repeated in the site-specificity of the premiere, its dynamic quality and the risk that the artists exposed themselves to at dizzying heights. However, THAW does not merely entertain at different urban locations. Instead, the performance aims to evoke a feeling of vulnerability in the dialogue between the dancers with ice and the audience, in order to open up a space for environmental reflection. The three dancers physically confront the ice to transform a male dominated understanding of nature. In particular, the third dancer, Isabelle Estrella, works with moments of visual storytelling to stage the figure of a tragic ice heroine. Dressed in a pair of dungarees with two hair braids and equipped with a Swedish Fjällräven backpack, her character resembles Greta Thunberg when she was still a child, probably one of the most famous climate activists. The activist notion of the performance is further stressed when the dancer unfurls a banner drenched in ice water which reads “No Time to Waste.”

Estrella’s performance begins with the examination of a mysterious object (maybe a lunch box), which ultimately breaks under her weight and almost slides off the ice. Similar to opening Pandora’s box, the dancer starts an emotionally-moving performance that oscillates between extreme feelings, such as hope and despair. Isolated on the slippery stage, Estrella’s struggles on the ice appeares as a world of its own. The dancer uses the safety catch (hidden in her clothes) to defy gravity by balancing in impossible postures, swinging over the ice or floating upside down – thus permanently changing her perspective. At one point, the dancer walks along the icy edge, using her movement to propel the iceberg in the opposite direction. In doing so, the performer makes herself the dominant rotational force of her own little world, thus reflecting on humans’ immense impact on ecological systems.

On another level of interpretation, the artists’ movement techniques de-humanise and subvert the figure of a human heroine, thus opening the viewers’ eyes to the non-human. The performer uses popping-and-locking or roboting techniques which generally convey an inhuman effect, heightened by pole-dancing and wall-running techniques, i.e. aerial artistry. The reference to circus forms of movement emphasises the utopian character of the performance and its imaginative potential for alternative worlds. At the same time, the continuous and increasing dripping of the melting iceberg – broadcasted via loudspeakers, together with electronic music – highlights the impending (and seemingly inevitable) threat of climate change.

The actual risk for the performer is difficult for the audience to assess. Since Estrella’s safety belt is hidden under her clothes and her suspension from the crane seems to be secured solely by the icing of the ropes, an emotional response from viewers is an essential part of the performance. In fact, there is a very real risk for the performer despite being technically secured – given the enormous height at which the performance takes place, and the physical strength that the aerial tricks require. The emotional effect of the performance even increases when the dancer repeatedly caresses the melting surface of the ice with her hands or when she douses herself with the ice water in a gesture of purification/baptism.

In her research on spectacular performances and their physical impact on the audience, Peta Tait emphasises the great affirmative power of aerial art, which uses physical danger as a key element of evoking connectedness (Tait 2005, 4). Following Tait, audiences’ identification with aerial artists triggers feelings of delight and anxiety, which often leads to a cathartic effect in the context of environmental communication (Tait 2020). At the premiere in Sydney, the experience of the artists – balancing on ice during – released an immediate physical reaction in the audience: they held their breath, clasped their hands and/or verbally expressed their concerns. In accordance with Tait, I interpret the affirmative quality of THAW as both emotional and physical. Since the Estrella’s existence depended on her increasingly-melting ice stage – forcing her to risk her life in a permanent battle – the performance mirrored our collective endangerment through accelerating climate change and our need to act. Like the heroine, we are losing our ground in an era of environmental extremes. Thus, two artistic strategies are central to THAW: 1. socialising effects and 2. evoking an individual threat.

In an upright, reverent, victory posture – with her hands clasped over her chest – Estrella finally accepted the applause at the end of the one-day performance. As a sign of successful collective formation, the enthusiastic audience reaction had a liberating effect. Although a catharsis as the result of ecocritical performance art can certainly be questioned, it is definitely preferable to an apocalyptic ending in which, for example, the iceberg completely melts or falls into the sea. Instead of being immobilised by a lack of possibilities, the performance thus preserved its social, community-building potential as well as its individual impact.

Conclusion: Environmental Arts and Sciences producing Planetary Knowledge

The activation of the audience was preceded by treating ice as a living phenomenon. In THAW, ice is not only a sign of loss, but also acts as an agent for sensually addressing the audience. It appears as a resistant and vulnerable non-human counterpart which is affected, yet ultimately uncontrolled by the dancer. Similarly, Estrella’s robotic dance style – her hovering, flying and diving above and beside the iceberg – blurs the boundaries between human and non-human life, thus fostering humanity’s connection with the world’s cryosphere.

Joanna Page defines the task of science-related art in climate change as a shift of agency, which “displaces us as humans from a privileged position as subjects and recreates us as co-agents of the aesthetic” (Page 2020, 291). According to Page, the assumption of a passive Earth and its availability for human needs must be replaced by a connection between all living things, through an aesthetic experience. In order to make the scientific knowledge of ecological dependencies tangible, THAW employs methods of de-scaling by presenting massive, global threat on one, tiny (ice) stage. In doing so, the performance confronts the cosmic insignificance of our existence with our harmful impact on the world’s ecosystems.

Environmental art that communicates the necessity of change is always activist in the sense that it evokes planetary knowledge. Planetary knowledge means that complex scientific understandings are internalised as a form of embodied knowledge. This form of inner environmental knowledge can only be evoked through the interweaving of science and art, as the performance THAW makes strikingly clear. Here, broad effectiveness – the awareness of individual as well as social responsibility – are generated through a sensual aesthetic in which ice gains an agency of its own. This is of great relevance for w/k, given the way sciences and ice art interrelate to communicate environmental urgency in times of climate change.

Literature

Bloom, Lisa: Gender on Ice: American Ideologies of Polar Expeditions, Minnesota 1993.

Leane, Elizabeth and Julia Jabour: Performing Sovereignty over an Ice Continent. In: Carolyn Philpott, Elizabeth Leane and Matt Delbridge (ed.): Performing Ice, London 2020, pp. 171–194.

Leane, Elizabeth Leane; Carolyn Philpott and Matt Delbridge: Performing Ice: Histories, Theories, Contexts. In: Elizabeth Leane and Matt Delbridge (ed.): Performing Ice, London 2020, pp 1–26.

Leane, Elizabeth: Icescape Theatre: Staging the Antarctic. In: Performance Research, 18/ 6, 2013, pp. 18–28.

Page, Joanna: Planetary Art beyond the Human. Rethinking Agency in the Anthropocene. In: The Anthropocene Review, 7/3, 2020, pp. 273–294.

Tait, Peta: Forms of Emotion: Human to Non-Human in Drama, Theatre and Contemporary Performance. London 2020.

Tait, Peta: Circus Bodies – Cultural Identity in Aerial Performance, London 2005.

Details of the cover photo: Legs on the Wall: THAW. (2021) Photo: © Prudence Upton.

How to cite this article

Anne Hemkendreis (2022): Ice as an Agent in the Aerial Performance "Thaw". w/k–Between Science & Art Journal. https://doi.org/10.55597/e7873

I am curious to know just how much electricity it takes to freeze such a huge lump of ice and how much diesel the crane 🏗 uses to suspend it all.

See here for more details: https://www.legsonthewall.com.au/take-action