Text: Anna-Sophie Jürgens and Mirjam Hildbrand | Section: On ‚Art and Science’

Abstract: This article examines how avant-garde artists were inspired by the circus and circus aesthetics, and used them as models for novel, polarising and sophisticated works of art. As the speakers – experts from an array of academic fields, theatre makers and circus practitioners – at the first symposium on Circus and the Avant-Gardes (March 2020, Freie Universität Berlin) examined, (studying) circus and avant-garde connections contributes to a better understanding of early 20th century artistic movements, the history of popular entertainment and the cultural relevance of circus arts.

Note: Articles exploring the interfaces between science and art in the field of Circus & Science are highlighted by a pink frame.

***

The performance practice of the circus in the early 20th century was formative for the avant-gardes. With the aim to produce a better sense of the artistic and cultural work that has emerged from the interplay of circus and avant-garde aesthetics and artistic strategies, and of their transhistorical presence and interdisciplinary expansiveness, the symposium Circus and the Avant-Gardes held at the Freie Universität Berlin (5-6 March 2020, supported by the Cluster of Excellence 2020 Temporal Communities: Doing Literature in a Global Perspective) brought together leading scholars from fields as varied as Drama & Theatre Studies, Literary & Cultural Studies, Slavonic Studies and Media & Film Studies. Over two days, academics and practitioners explored how the aesthetics of circus arts affected and competed with the theatre of the Russian and Western avant-gardes, and to what extent the circus served as an inspiration for multimedia avant-garde productions, for example in film. They carved out new dimensions of the richness and multidimensionality of the circus’s cultural capital by asking questions such as:

- In what ways did the aesthetics of the circus and related stage genres (such as vaudeville, variety, music hall, etc.) affect the artistic styles of avant-garde artists?

- How did technologies of the circus inscribe themselves into the works of the avant-gardes?

- What can we learn from the different scholarly perspectives on the interplay between avant-garde art and circus arts?

Revolving around these questions, the symposium added new perspectives on the competing creative forces that demanded and designed the theatricalisation of the circus and the circensation of the theatre (O. Bulgakowa) around and after 1900.[1] It also elucidated how popular performance was, and is, significant for the present – and how the realm of the circus as a model for experiment, innovation and (re)negotiation of bodies has become fully integrated in our ways of perceiving the historical avant-gardes today.

Mesmerising avant-garde artists: on the creative power of circus arts and clowning

The online journal w/k – Between Science & Art explores the interfaces between science and art. The title of the online journal ‘w/k’ refers to the German language terms ‘Wissenschaft’ (science) and ‘Kunst’ (art). Usually ‘Wissenschaft’ is translated as ‘science’, although the German term is much broader and includes every systematic knowledge producing enterprise and research activity, and thus also, for instance, the Humanities (for more details see here). What makes Circus and the Avant-Gardes an interesting subject of discussion for w/k is the fact that circus aesthetics and performance routines have shaped not only avant-garde theatre and film makers (e.g. Max Reinhardt, Vsevolod Meyerhold and Sergei Eisenstein), but also helped constitute the creative works of painters, graphic artists and book designers, as well as the avant-gardists exploring the realms in-between these genres and artistic fields. A fascination for circus-inspired physical culture, artistic expression and the mischievous-clownesque can be found in the works of many Bauhaus artists. The enthusiasm of Russian artists (e.g. Grigori Kozintsew, Leonid Trauberg and Sergei Yutkewitsch) for the circus coincided with their efforts to reform the medium of communication in theatre, and its stage. László Moholy-Nagy and Oskar Schlemmer, for instance, were interested in the geometry of the movement of a human body in abstract space. Intensely inspired by circus and dance, and following their vision of freeing man from the manifold bondages of physical limitations, Schlemmer and his team created elaborate hyper-sculptural costumes in the 1920s – personifications of the unification of costume, dance and music – that transmogrified dancers into artificial figures. According to Schlemmer, circus was an artistic institution[2] with a potential to reform art, while Moholy-Nagy proclaimed that circus, operetta, variety and clowning (Charlie Chaplin, Fratellini) were to act as models for the abolishment of subjectivity.[3] Studying the avant-garde movements with a focus on circus, it becomes clear that the circus imaginary served as an important source of inspiration not only for the reformation of the drama-based theatre but also for the theorisation of avant-gardist visions for the performing and fine arts.

Reforming art and theatre through circus was also a vision of Futurist artists – above all Marinetti, who visited the Cirque Médrano in Paris together with Picasso and Apollinaire and possibly Meyerhold.[4] The circus, which naturalism had considered a microcosm of primarily social interest, was now perceived as an aesthetic space; a space of strong contrasts of light and color. As the academics at the symposium Circus and the Avant-Gardes noted, within this context, the clown figure took on many different roles and forms in the works of avant-garde artists. In his work, Marinetti, for instance, celebrates two concrete circus archetypes: the aerial acrobat and the clown. For Marinetti, the clown embodies a specifically theatrical and sensitive attitude towards the world as well as the grotesque, with an anarchistic-subversive trait (influenced by Nietzsche). The clown is one of the most complex protagonists in the circus, who not only stirs up the sawdust as a weird outsider and creature of poetic imagination, but also appears as a suspicious jester, rascal and melancholic. He appears, moonstruck, in Schönberg’s melodrama Pierrot Lunaire; he dances as Petrushka in Stravinsky’s ballet of the same name and is captured on the screen by Chaplin as Tramp. There is no shortage of this circus figure in the fine arts, either, whether painted by Rouault, who created the clown tragique, which gave Pierrot his iconic features; or by Chagall, who allowed impossible, gravitation-free perspectives on the circus theme. Léger and Miró designed the clown as a surreal harlequin; Toulouse-Lautrec shows him in graceful abjectness and Picasso in the shape of Minotaur. The reach of clown imagery demonstrates how embedded clowns are in the art and culture around 1900 and the beginning of the 20th century. As the symposium Circus and the Avant-Gardes showed, circus and circus phenomena have lost none of their fascination. In 2019/2020, for instance, the interplay between the clown characters and avant-garde art can be admired at the Komische Oper Berlin in plays such as Petruschka (Strawinsky/Benois) and L’Enfant et les Sortilèges (Ravel/Colette), as Ulrich Lenz, the head dramaturge, explained in a public round table discussion as part of the symposium.

Zooming in: scholarly perspectives on the interplay of avant-garde and circus art, technology and science

Popular entertainment has always been intertwined with the cutting edge of technology. Insights into circus practice and the interplay between circus and technology around 1900 were provided by Mirjam Hildbrand (University of Bern) and För Künkel at the symposium Circus and the Avant-Gardes, focusing on the situation in Berlin. As uncovered in their presentation, important circus shows took place in pompous circus buildings (none of them still exist today) that, in most cases, disposed of an arena and a frontal stage. The circus artists performed in front of a large, heterogeneous audience as the venues contained between 3000 and 5000 seats. The programmes were also very attractive for the audience as the circus companies immediately introduced the latest technologies (such as electric lighting and lighting effects, hydraulic systems, revolving stages) into their buildings as well as into their shows. They even added new cinematographic projection technologies to their programmes after the creation of the first film projectors in 1895. The circus arts around 1900 not only consisted of opulent programmes with various enticing acts, but also of narrative, full-length shows dealing with current societal and political topics as well as themes from tales, operas, heroic sagas, etc. These multimedia circus shows in the arenas and on the stages of the circus buildings around 1900 can be seen as predecessors of the concepts of famous avant-garde artists as Erwin Piscator, Max Reinhardt and László Moholy-Nagy (see above). Other stages for the interplay of avant-garde (circus) art, technology and science can be found at the beginning of the 20th century in early film and artistic book design.

Typocirkus

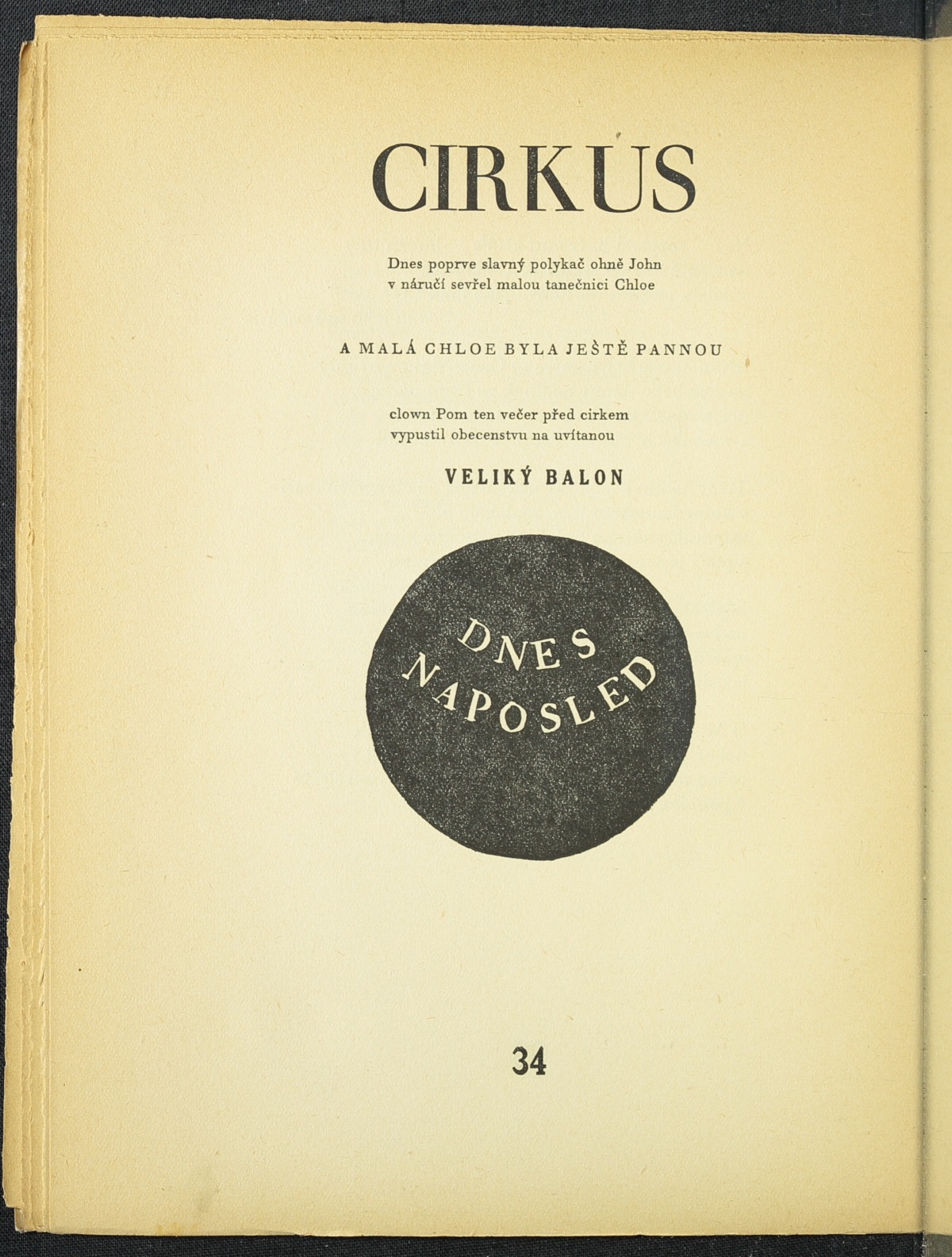

One of the participants of the symposium, Anne Hultsch (University of Vienna), gave a talk on the so-called Typocirkus of the Czech avant-gardes in the 1920s. Authors, graphic designers and typesetters collectively created books that were inspired by the commonly-known circus imaginary (embodied, for instance, in the round shape of the circus ring) as well as the advertising strategies of travelling circus companies. For example, ‘Dnes naposled’ (‘Today for the last time’) was an expression circus companies used for their ads. We can find this expression on and in many Typocirkus works, for instance in Cirkus, a text by Jaroslav Seifert, typography by Karel Teige (one of the most famous Czech modernist avant-garde artists).

Seifert, Jaroslav: Cirkus, in: idem., Na vlnách TSF, typography by Karel Teige, Praha 1925, p. 34.

It was not only the covers of these various books that were elaborately designed; the inside of the book had a specific and sometimes adventurous, artistic layout. More precisely, the typographers and layout artists finalised the composition of the text with their layout. They redefined the rules of classical typography, for instance by using unusually large, wildly placed letters; they invented new fonts and mixed different fonts in unprecedented, daring ways. This practice brought the circus to the print houses along with a huge printing challenge. As the typesetters were running from letter case to letter case throughout the whole case room in order to typeset a book, it does not come as a surprise that critics called the printing process itself ‘a circus’. The Typocirkus books were printed in large editions and can still be found in many homes in the Czech Republic. Interestingly, the Czech avant-garde graphic artists probably did not attend contemporary circus performances and thus did not know actual circus practice. Nevertheless, the inspiration for Czech avant-garde art from the circus is undisputed. Typocirkus books display a high degree of abstraction and adopt the design of circus posters in literary texts. The understanding of avant-garde literature would only remain fragmentary without taking into account the – visual and verbal – references to the circus. From the point of view of Cultural and Literary Studies, it is particularly interesting that the reception of the circus by avant-garde artists points to the materiality of the texts and to visual forms of communication that challenge the perception – and show how the form becomes a function of the content.

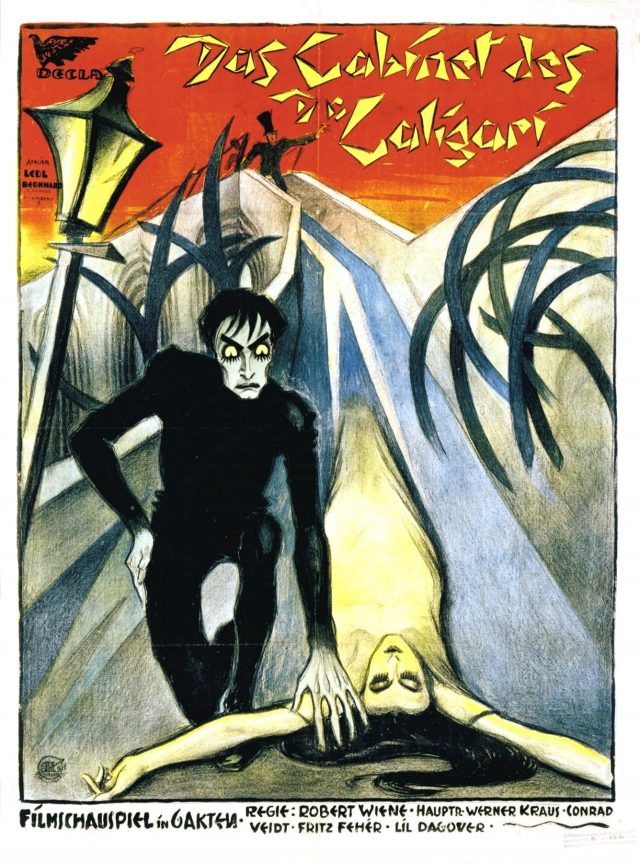

Caligari, the mad-scientist-showman

One of the most influential expressionist films, the silent horror film The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari (1920, directed by Robert Wiene ), tells the story of carnival mesmerist Caligari (Werner Krauss) and his sleepwalker slave, Caesare (Conrad Veidt), who transforms into a killer automaton and zombie slave through his master’s hypnotic power. Caligari has been called the prototype of ‘the megalomaniacal pseudoscientist who controls a soulless monster’.[5] At the symposium Circus and the Avant-Gardes, Hans Richard Brittnacher (Freie Universität Berlin) explored the ways both the film’s references to circus and unorthodox science, and the extremely influential avant-garde[6] set design with its abstract, bold (viewing) angles and artificial lightning – itself referring to art historical predecessors from the fields of painting, theatre and literature – inspired artists and writers of the 1920s and 30s.

Caligari reflects and challenges the anxiety of being exposed to the modern world – subjected to, but not the subject of, modernity – and the expressionist desire to reimaging human agency and individual autonomy[7] by exploring issues around the control and power over the human body on show. The film can thus be linked to both a larger realm of cultural expression exploring bodily control and loss of control, known at the beginning of the 20th century as nervous disorders (hysteria, epilepsy, and neurasthenia), and to a dominant body language in pre-cinematic mass spectacles that inspired avant-garde artists: bizarre contortions and dislocations, jerking and gesticulating, and tics and grimaces – eccentric movements intertwining with scientific observations in the field of psychophysiology and psychiatry on the nervous system. As shown at the symposium, the line of hysterical gesture and gait that can be seen everywhere from early 20th century circus paintings and cabaret and café-concert performances through to the films of Georges Méliès, Charlie Chaplin, Ernst Lubitsch and Jerry Lewis, also live on in contemporary films featuring violent clowns, most recently in Todd Phillips’ Joker.

In sum, the presentations at the symposium Circus and the Avant-Gardes demonstrated that studying the approach to circus by avant-garde artists provides a richer account of the circus’s past, its interplay with technology and science related spheres, and its endurance and transportability – how circus arts influence art, and how they are formative for the present and the future.

Picture above the text: EXC 2020 Temporal Communities: Circus and the Avant-Gardes: Multimedia Technologies and Popular Body Machines (2020). Foto: EXC 2020 Temporal Communities.

The symposium Circus and the Avant-Gardes included presentations by Prof Oskana Bulgakowa (Mainz), Dr Dr Anne Hultsch (Vienna), Dr Olga Burenina-Petrova (Zürich), Prof Hans Richard Brittnacher (Berlin), Prof Cornelia Ortlieb & Mag Lara Tarbuk (Berlin), MA För Künkel, Prof Julie K Allen (BYU, USA), Dr Martina Groß (Hildesheim), Jun-Prof Eva Krivanec (Weimar), MA Mirjam Hildbrand (Bern) & Dr Anna-Sophie Jürgens (Canberra).

A second symposium on Circus and the Avant-Gardes will be hosted by the Institute of Theatre Studies at the University of Bern and will take place in the virtual space on 13-14 May 2020.

▷ Follow our circus and avant-garde adventures on Twitter: #circus_avantgardes!

Funded by the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (DFG, German Research Foundation) under Germany ́s Excellence Strategy in the context of the Cluster of Excellence Temporal Communities: Doing Literature in a Global Perspective – EXC 2020 – Project ID 3900608380.

[1] Bulgakowa, Oksana: FEKS: Die Fabrik des Exzentrischen Schauspielers [The Factory of the Eccentric Actor], Berlin 1996.

[2] Schlemmer in Brauneck, Manfred (Ed.): Theater im 20. Jahrhundert: Programmschriften, Stilperioden, Reformmodelle [20th century theatre: programmes, style periods, reform models], Reinbek bei Hamburg 1993, p. 149.

[3] Moholy-Nagy, László: ‘Theater, Zirkus und Varieté’ (1925), in: Brauneck, Theater im 20. Jahrhundert (see Endnote 2), pp. 154-161 (p. 158).

[4] Lista, Giovanni: ‘Esthétique du music-hall et mythologie urbaine chez Marinetti’ [Music hall aesthetics and urban mythology by Marinetti], in: Claudine Amiard-Chevrel (ed.), Du cirque au théâtre [From circus to theatre], Lausanne 1983, pp. 48-64 (pp. 51-52).

[5] Dinello, Daniel: Technophobia!: Science Fiction Visions of Posthuman Technology, Austin 2005, p. 55.

[6] Cf. Woeller, Marcus: ‘In den Zwanzigern waren selbst die Kulissen Avantgarde’ [Even the backdrops were avant-garde in the twenties], Die Welt, 02/07/2019, https://www.welt.de/kultur/kunst/article196199563/Filmarchitektur-In-den-1920ern-waren-Kulissen-Avantgarde.html

[7] See Cowan, Michael: Cult of the Will: Nervousness and German Modernity, University Park 2008, p. 86.

How to cite this article

Anna-Sophie Jürgens and Mirjam Hildbrand (2020): Circus Arts and the Avant-Gardes. w/k–Between Science & Art Journal. https://doi.org/10.55597/e5893

spisok

spisok

… [Trackback]

[…] Find More Info here on that Topic: between-science-and-art.com/exploring-circus-arts-and-the-avant-gardes/ […]

… [Trackback]

[…] Find More on on that Topic: between-science-and-art.com/exploring-circus-arts-and-the-avant-gardes/ […]

Tucker Carlson – Vladimir Putin

Tucker Carlson – Vladimir Putin

Tucker Carlson – Vladimir Putin – 2024-02-09 Putin interview summary, full interview.

Tucker Carlson – Vladimir Putin – 2024-02-09 Putin interview summary, full interview.

samorazvitiepsi

samorazvitiepsi

000

000

laloxeziya-chto-eto-prostymi-slovami.ru

laloxeziya-chto-eto-prostymi-slovami.ru

123 Movies

123 Movies

film2024

film2024

batman apollo

batman apollo