In conversation with Anna-Sophie Jürgens | Section: Interviews | Series: Street art, Science and Engagement

Abstract: In this article, archaeologist Dr Duncan Wright explores the intertwined realms of rock art and street art. Through an examination of the motivations, methods and materials of rock artists, Wright offers a nuanced reflection on these creative expressions (and their meanings) in their specific cultural contexts. The article investigates geographical, historical and cultural research-based dimensions of art on walls, coupled with an insightful analysis of the intersections between rock art and graffiti/street art, to better understand the power of public art in communicating knowledge.

Dr Duncan Wright, it is a great pleasure to welcome you to the online journal w/k! You are an Associate Professor in Archaeology at the Australian National University (ANU), specialising in Australian Indigenous archaeology. In your research and teaching you are interested in resurrecting stories through ethno-archaeology, past ritual and religious experience and the archaeology of art (among many other things). At ANU you teach a course in which you and your students explore graffiti and street art and their relationship to rock art and ritual forms of writing, including discussing graffiti pieces on campus so that students can engage with the subject while standing directly in front of painted walls. All of this is extremely interesting to w/k, and in this article we would like to invite you to share your thoughts on the connections and different facets of art on walls across time and cultures, how to research them and why they are so significant for us today and in the future, with the aim of better understanding the power of public art to communicate knowledge.

Great to be here.

Researching Rock Art

Duncan, it would be wonderful if you could start with an introduction to rock art – what is rock art?

From my perspective as an archaeologist, rock art is human-made markings on stone surfaces – for example rock shelters and caves. This includes paintings (additive), petroglyphs (reductive), sculptured rock reliefs and geoglyphs that are arranged on or cut into the ground.

Rock art is global and timeless, produced by cultures from around the world from at least 40,000 years ago and continuing to this day in forms that arguably include street art. In all contexts these sites provide highly evocative windows on past lives because the artist presents important moments in their lives and does it in a way that showcases clothes and accoutrements that (being organic) are highly unlikely to survive outside this record. We can see ceremonies underway, better understand how our ancestors enjoyed their lives, what they ate and wore and even get echoes of how they placed themselves within the universe. On a rock art survey coordinated by rock art scholar Sally May in Arnhem Land, I looked at one rock shelter and saw people singing and playing the didgeridoo back at me! The artist had painted dotted lines streaming from people and instruments.

You previously said that rock art raises the question about who is allowed to do art. Is rock art sacred?

I talked to Graham Badari about this many years ago, out the back of Injalak Arts Centre|Based in Gunbalanya, Northern Territory (personal communication 2015). He made it very clear that there are some djang (ancestral creation stories) which he can paint but many others for which he has no rights. I further attempted to understand the separation between sacred and secular within his art only to realise (as Graham became more and more bewildered) how culturally naïve my questions were. Spirit and real worlds are to all intents and purposes one and the same. Another mind-bending concept that Graham introduced me to was that art could be alive and animate. Rock paintings on Injalak Hill (an important cultural site a few hundred metres away from Injalak arts) were not seen as ancient paintings. Mimi figures (spirit tricksters in local folklore) had always been there and would come out of the rock each night!

Community-based research in northern Australia has identified further complexities. Taylor (1996), for example, describes gradual revelation of sacred knowledge within art. At face value a painted barramundi represented a fish that is good to eat, however, Bininj (Aboriginal people of western Arnhem Land) were able to look at colour preferences within the rarrk (cross hatching patterns within the paintings) and identify a particular artists/family of artists and the region in which the ochre was collected, and understand Dreaming stories and teachings that underpin this painting.

Howard Morphy (1999) provides another fascinating example: a painted object, displayed during ceremonies, was initially described to new initiates as representing a place called Wallaby Waterhole (represented by a circle) and Kangaroo Creek (two parallel lines). Many years later the initiate was told that the waterhole was made by old man kangaroo who dug the waterhole using his tail as a digging stick. The circle still represents the waterhole while the parallel lines now become the digging stick tail. Many years later the initiate is provided with another layer of information. Without giving too much away, the parallel lines represent both the path taken by Kangaroo Creek and the penis of Old Man Kangaroo, while the circle is both a waterhole and a Wallaby vulva. In this way, art intersects with ceremony, language, toponyms (place names, often derived from a topographical feature) to reveal and conceal sacred knowledge about an important Dreaming story.

Interpretation of the sacred in art outside of First Nations contexts is … even harder. There’s the added conundrum – how relevant are observations (such as those made above) for contexts removed by so much time and space? Clearly there are problems making huge leaps of faith. At the same time, I think that we are unwise to ignore perspectives of people arguably better able to associate with the hunter-gatherer societies responsible for this art. Let’s look at 17–20,000 year old art at Lascaux in France (e.g., Wallis et al. 2021). Amongst the 6000+ individual motifs it contains there are many abstract designs or symbols. These designs are repeated across this and other art sites, also on portable art objects excavated within the region. It is plausible that we are viewing a system of symbols, as might be expected within a unified belief system, that was understood differently depending on level of initiation. Returning to Graham Badari’s comments, it may well have been that the painted animals themselves were seen as alive and sacred. An interesting observation made at Lascaux was that there are no images of reindeer, even though reindeer make up the majority the food remains found in the excavations at this site (e.g., Wallis et al. 2021). This, coupled with the location of art within the cave’s dark zone, suggests we are seeing intermingling of spiritual and secular worlds. How far down this rabbit hole should we go? It may be that the pigments used by these artists were also important, transporting a story about an area that was also considered sacred.

Do you work at publicly accessible Aboriginal art sites (e.g. in National Parks) or, more generally, how do archaeologists interested in exploring rock art find the art and walls, and gain access to them?

The projects I work on are usually driven by First Nations communities and all of them only occur if permissions are in place. A cultural heritage assessment may be requested by elders working towards cultural tourism initiatives or native title claims and during this exercise we may discover and record rock art alongside many other heritage sites. Occasionally, while completing projects I hear about rock art sites and ask to visit them. This happened last year. A fisherman discovered engravings on an island in central Torres Strait. I reached out to the Chairperson of the relevant Prescribed Body Corporate (PBC) and asked whether he knew about this site and/or wanted it recorded. He was keen and we found ourselves soaked to the skin, bouncing along in a dinghy towards this uninhabited island!

How do archaeologists study and interpret rock art?

I should start by saying that I am no rock art expert. My answer is based on experience completing basic site recording while detailed stuff was left to those with considerably more training. That said, rock art study usually covers the same components and becomes increasingly complex depending on the size and/or importance of the site. Field recording may look something like this:

- A preliminary site assessment. Recording site location using a GPS, basic site and rock art descriptions focusing on robust features likely to survive for many decades/centuries. Site information usually includes compass bearing, site size, approximate number of motifs, rock art techniques represented (e.g. pecked, scratched, stencils etc.), key motifs, colours and superimpositions. Usually this would be accompanied with a photograph with scale and a drawing of the site.

- Should the site merit further attention then a detailed site recording will occur. This incorporates everything outlined above, also detailed drawings (occasionally 3-D photographic mapping) of the site. Rock art recording is meticulous, with archaeologists required to identify conservation issues and all superimpositions, thereby getting a good idea of age/sequence of art events. A Munsell chart (along the lines of the colour match system you might use when ordering paint at Bunnings) may be used to obtain robust definitions of colour and the entire rock surface photographed so that hidden rock art may emerge when run through computer programs e.g. D-stretch. Samples may be taken for radiocarbon or other dating.

At each stage the archaeologist needs to separate out descriptive from interpretive information. We bring our own cultural biases to the table and an important skill is to be as objective as possible.

Ultimately, the first stage ensures we have dots on the map and enough information to return to this site should we wish this. The second stage preserves considerable information about a site. In Australian contexts – in which sites are threatened by fire, livestock etc. – preservation of this information may be invaluable.

What can we learn from rock art about the environment?

Environment plays out in rock art in many different ways. Without going into huge amounts of detail, animals and plants have always been important in our lives and therefore it is natural these themes will be depicted in rock and portable art. In my experience it is particularly exciting when you come across an animal which you know to be extinct or vegetation that is totally different from what is around today. In Arnhem Land in Australia I was lucky enough to come face-to-face with rock art depicting a Tasmanian tiger (thylacine) and her cubs. These animals became extinct on this continent at least 2000 years ago but it was all too easy to imagine the artist watching these animals running across the adjacent flood plains.

Much can also be learnt about cultural environment. We learn, for example, about regional groupings through stylistic differences. There are even case studies in which clan and linguistic boundaries may be mirrored by clear differences in rock art styles (e.g. Taçon 1993). Beyond this, I always get the feeling when completing site surveys that sites were chosen carefully. Rock art, stone arrangements and many other natural and cultural features provide architectural bones to this country.

Rock Art and Street Art

In our last conversation, you said that rock art, graffiti and street art are “analogous”. What do you mean by that?

As mentioned above, some argue that rock art closely compares with street art and even graffiti (e.g. Chippindale and Tacon 1998; Nash 2010). Where do we draw the line? Graffiti has existed since ancient times, with examples dating back to ancient Egypt, ancient Greece and the Roman Empire. In my mind, the artists who painted rock art galleries in northern Australia, Palaeolithic cave sites in Europe and Sisters Rock (a graffiti site in Victoria, Australia) were motivated by similar desires – to mark country, make social commentaries and have their work seen by other people. It makes sense that archaeology informs street art (e.g. Wandjina rock art moving onto the street – Fredrick and O’Connor 2009) and vice versa. There are so many shared questions – what subversive, anti-establishment values exist within this art? Was art a marker of stress or territoriality? What parts of these drawings are the product of an individual or collective creative act? Can we trace artists based on their style? Can we trace significant trackways/ landscapes based on art content and/or symbolic vocabulary? Another question, one that will be very clear to those who have spent time at Aboriginal art centres, relates to revelation and restriction of knowledge. How might secret information be buried in plain sight? Who has the right to paint each story?

Would you say that what rock art and street art have in common is that they create a sense of belonging?

Quite possibly. Our species seems to delight in emplacing ourselves through art. Look at the many installations scattered around Canberra for an example! The same is likely to be the case for past peoples including the first arrivals on this continent. With each site established people became increasingly intertwined with their environment. Every time a repainting event occurred, the artist was both associating themselves with country, and also with the ancestors who had painted this shelter before them.

Understanding Rock Art through Street Art

When you take your students to a street art wall on the ANU campus in Canberra, what do you discuss there?

We start by discussing ways in which street and rock art are analogous. Street art also provides an excellent series of paintings that we can map and record using archaeological techniques. This leads to exercises in which students use the techniques described earlier to assess a panel. We finish with a discussion about how far we can go interpreting motivation/cultural backdrop for this art. What can we learn about the sequence of art based on superimpositions of motifs? Why might the artist/s have painted over previous images? Is this a deliberate attempt to obscure what comes before or something more positive – adding to the importance of the site through ongoing engagement?

I think students get a real kick out of this exercise. It’s a site close to home and yet they are transported to another place entirely. Art inspires storytelling and there is often much discussion before we call it a day!

Superimposition and Overwriting

Duncan, you mentioned layers of meaning above … In Australia there are many sites with Aboriginal art – places of the Aboriginal community where ancestors and important stories are depicted – which were overwritten some centuries ago (e.g. during the time of the gold rush) by immigrants who carved into the rock, but also since then. There are also sites where people have started to graffiti over rock art. As an archaeologist, what do you think of this type of superimposition?

The superimposition debate remains a hot topic. Let’s start with an example. Sisters Rock near Stawell in Victoria is one fascinating place (see Griffin and Watson 2014). It is both an important site for the local Aboriginal community (affiliated with the Bunjil Ancestor) and for those with European heritage (because of its association with the Levi sisters who reputedly camped here during the gold rush).

Every inch of these granite tors is covered in graffiti, a practice that began in the 19th century continuing to the present. They are superimposed over one another and reputedly also rock art associated with Bunjil. On one hand this may be viewed as modern rock art that connects the place through time with people with very different heritage marking this place out of a shared connection. Another interpretation is that graffiti is defacing a site that is important to Aboriginal peoples in this area and it must be stopped. Over time the views of First Nations and non-Indigenous Australians have differed on this topic. How best to juggle these competing connections and priorities? Mutual respect and dialogue between stakeholder communities. Does this happen? Not always.

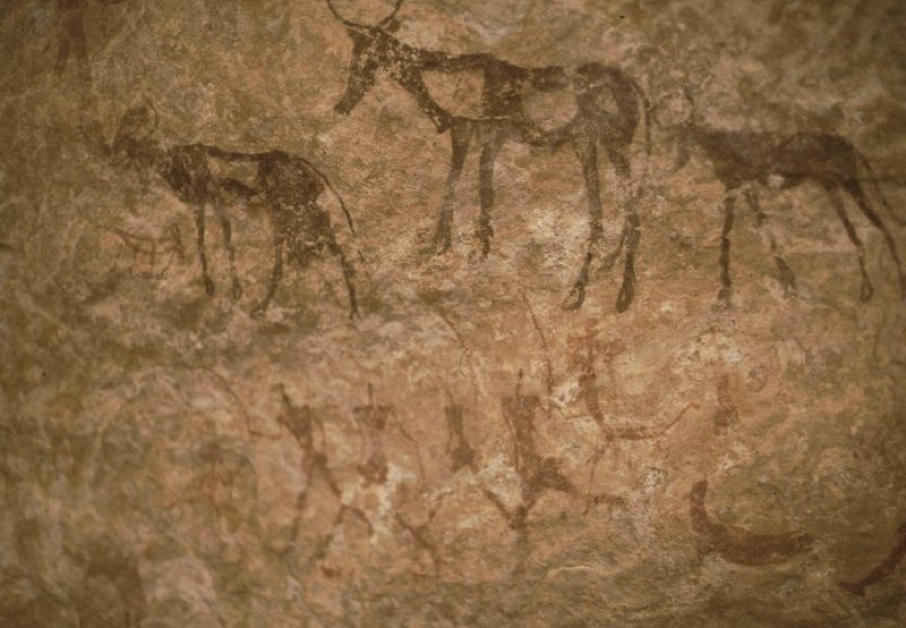

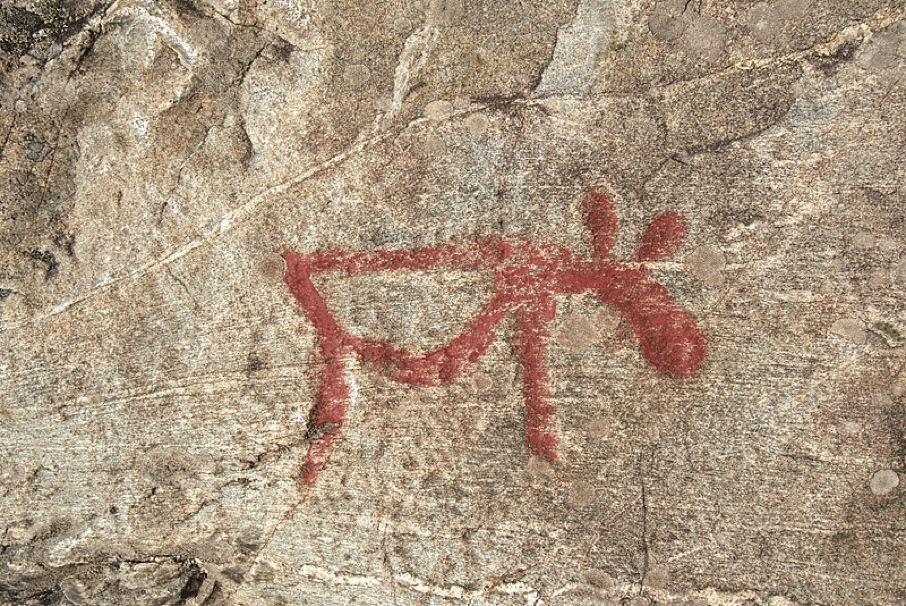

Speaking of superimposition and interpretation … Let’s add another layer! Canberra-based AI artist TA used your answers to my previous questions about rock art and street art to create the two AI-generated images below and the cover image. What do you think of this type of technology-empowered superimposition – and visual dialogue – that brings together (and adds more!) complexities around art on rocks and walls?

I agree. AI (in particular machine learning) will undoubtedly have a huge role to play in how rock art is recorded in the future – providing statistically robust studies into authorship and style boundaries.

Do these images echo my own engagement with rock art? Yes and no. These images are evocative. They promote some of the excitement and wonder felt when walking across cultural landscapes. Ultimately, there is no substitute for experience. Sitting in front of a painting and thinking about how this scene played out hundreds, even thousands of years ago, is very special.

Duncan, thank you very much for this fantastic conversation!

References

Chippindale, C. and Taçon, P.S. eds. (1998): The archaeology of rock-art. Cambridge University Press.

Frederick, U. and O’Connor, S. (2009): Wandjina, graffiti and heritage: The power and politics of enduring imagery. Humanities Research, 15(2), pp.153–183.

Griin, D. and Watson, B. (2014): Sisters Rocks: changing connections to a sacred place.

Nash, G. (2010): Graffiti-art: can it hold the key to the placing of prehistoric rock-art?. Time and Mind, 3(1), pp.41–62.

TA: Occulta Mundi (artist website), 2024.

Tacon, P.S. (1993): Regionalism in the recent rock art of western Arnhem Land, Northern Territory. Archaeology in Oceania, 28(3), pp.112–120.

Taylor, L. (1996): Seeing the inside: bark painting in western Arnhem Land. Oxford University Press.

Wallis, R.J. (2021): 15 Hunters and shamans, sex and death. Ontologies of Rock Art: Images, Relational Approaches, and Indigenous Knowledges.

Details of the cover image: TA: Petra Pictura II (2024). Image: TA.

How to cite this article

Duncan Wright and Anna-Sophie Jürgens (2024): Duncan Wright: Rock Art and Street Art. w/k–Between Science & Art Journal. https://doi.org/10.55597/e9459

Be First to Comment