Text: Julia Frese & Till Bödeker | Section: Border Crossers | Exhibitions

Abstract: The exhibition CHE$$ by Till Bödeker at Weiden Space presents a chess-inspired perfume titled CHESS. It addresses the fusion of art and consumption, inspired by Marcel Duchamp and chess, and communicates on both a visual and olfactory level.

Editor’s Preface

w/k editor-in-chief Till Bödeker is a border crosser between fine art and science at the level of his studies: he is part of Rita McBride’s class at the Kunstakademie Düsseldorf. Having studied philosophy and German language and literature at Heinrich Heine University, he works at the Chair of Metaphysics and Philosophy of Science; his most important philosophical teacher is w/k co-editor Markus Schrenk, with whom Bödeker pursues (art) philosophical research projects. He is therefore active both artistically and academically.

The art of border crossers is not always science-related. A prime example of this is Karl Otto Götz, who combined his informal painting with the development of the psychological Visual Aesthetic Sensitivity Test (VAST). The art of border crossers is also relevant for w/k where it is not primarily science-related. That is why CHE$$ is presented here.

The following text is a revised version of an article by Julia Frese that was published in the online blog squares & symbols.

…..

The exhibition CHE$$ took place at Kunstraum Weiden Space from December 22 to 31, 2023. The invitation announces that Till Bödeker will present his “chess-inspired perfume CHESS”. This text first describes the visitors’ impressions and then describes the artistic concept of the exhibition in more detail.

Part 1: Impressions

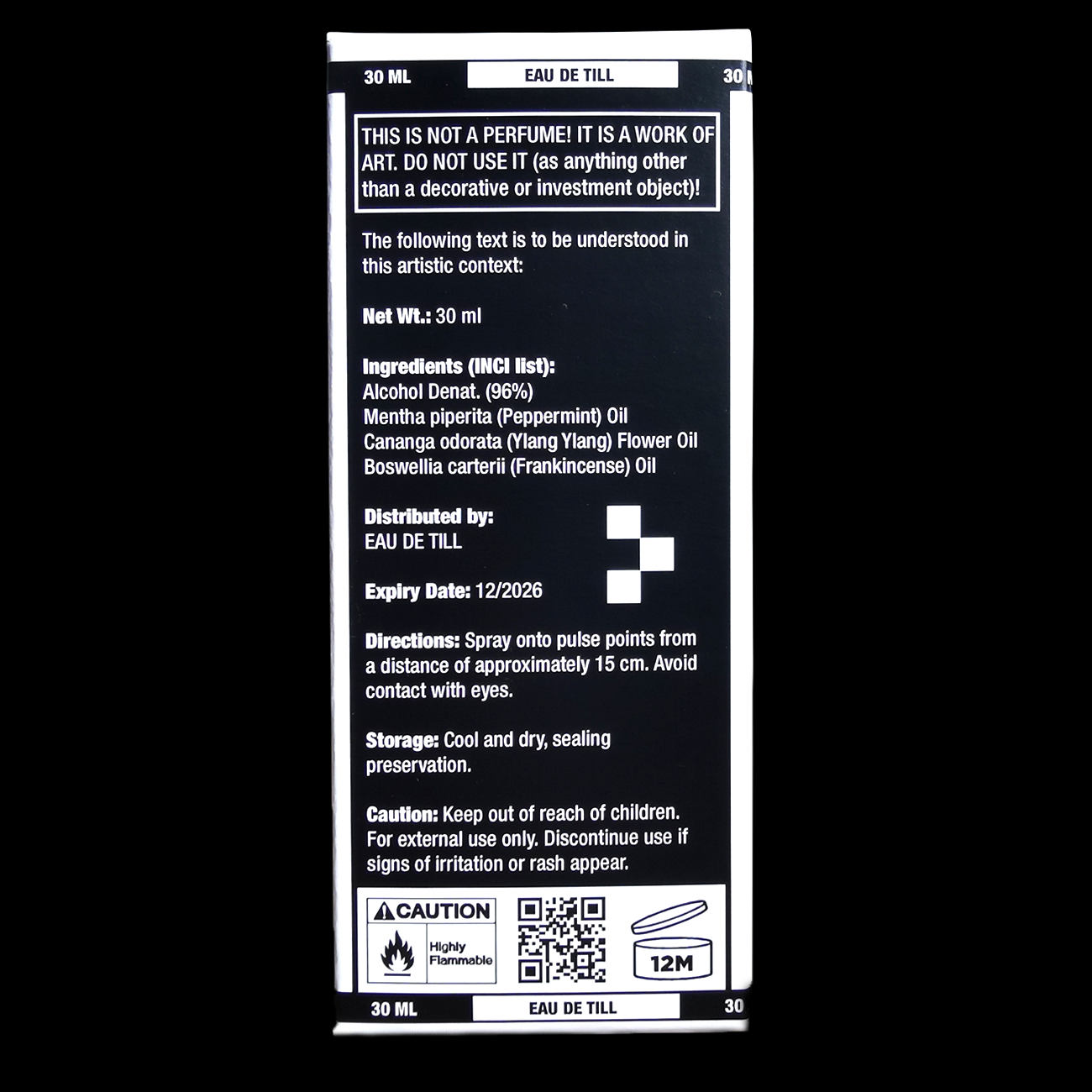

From the outside, the window of the art space is reminiscent of a pop-up store. Commercials for the perfume CHESS are projected onto the window surface. As you enter the room, the eye is drawn on to the large, black lettering CHE$$ (with two dollar signs!), the title of the exhibition, which extends across a corner on two walls. On the floor in front of the lettering, packages of perfume form a pyramid-shaped construction. Each package bears the inscription “CHESS”. The number and arrangement of the perfume boxes creates the impression of a sculpture. The following text appears on the back of the packaging:

THIS IS NOT A PERFUME! IT IS A WORK OF ART.

DO NOT USE IT (as anything other than a decorative or investment object)!The following text is be understood in this artistic context:

Net Wt.: 30 ml

Ingredients (INCI list):

Alcohol Denat. (96%)

Mentha piperita (Peppermint) Oil

Cananga odorata (Ylang Ylang) Flower Oil

Boswellia carterii (Frankincense) Oil[…]

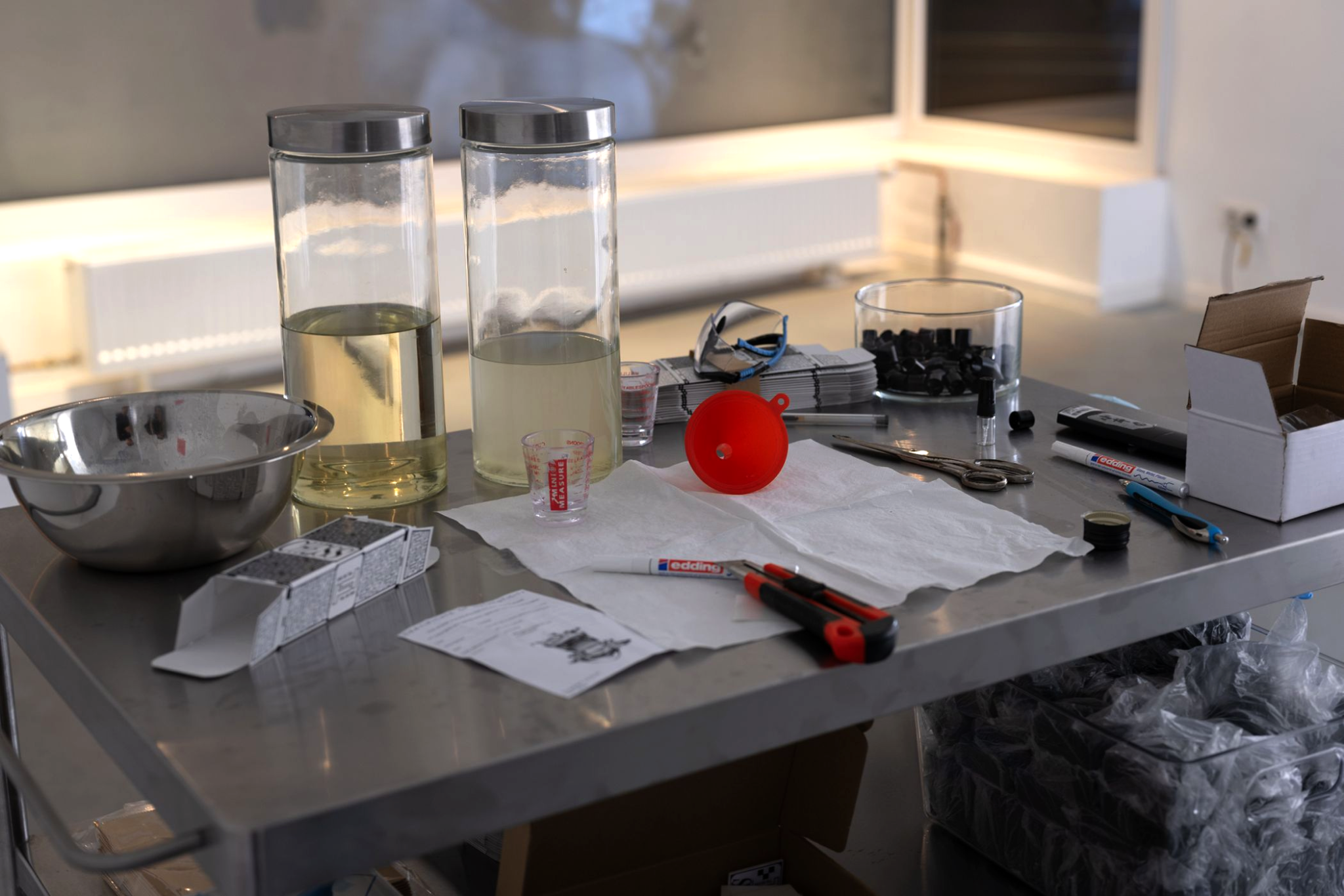

The smell of perfume permeates the entire exhibition. It intensifies when a visitor decides to buy a perfume, as Bödeker then begins to fill one of the empty bottles on a serving trolley with the perfume liquid. This is then placed in a package sealed with a red “Eau de Till” sticker. The number of the bottle is indicated on the back of each perfume bottle sold; Peter Tepe, for example, has been given the number “7”.

At the back of the room are several pre-filled perfume bottles. The lids of these bottles are transparent and are reminiscent of the queen’s chess piece or her crown, lined up on a long, narrow plinth covered in black velvet fabric. The installation is illuminated by bright LED spotlights and casts dark shadows.

A 3D printer and a station for cleaning and post-curing 3D prints stand on metal shelves attached to the wall. On the opposite wall hangs a small metal stamp engraved with the negative of the badges attached to the front of the bottles. There is also a table with a chess set at the back of the exhibition space.

Going back to the commercials that can be seen on the outside and inside of the shop window, these consist mainly of black and white stock footage clips, i.e. film material from license-free Internet archives. The scenes alternate between a black cat and a little girl pouring milk into a glass in slow motion. With each new cut, the words “BLACK”,“WHITE”,“SCHWARZ” or “WEIß” appear in large letters. Dramatic music accompanies the visuals while a woman’s voice whispers the words. Then the chess-inspired perfume bottle comes into focus. A deep male voice announces: “Chess, the new fragrance from Eau de Till”. Each commercial ends with an excerpt from an interview with a restless young man telling a reporter: “Chess speaks for itself”. When asked if the man would really never wear any other perfume (“Is there really no other perfume you would ever wear?”), the man, already hurrying away, gives no answer.

Part 2: Concept

Central to the CHE$$ exhibition is Bödeker’s CHESS perfume, which could be purchased on site in an edition of 100 (and can still be bought online). According to Bödeker, the sale and promotion of CHESS as a consumer product are to be understood as conceptual components of the exhibition, which explains the dollar signs in the exhibition title. Before going into this context in more detail, some of the exhibition’s references should be explained.

2.1 CHESS Smells For Itself

First of all, the slogan “CHESS Smells For Itself” is written on the inside of the lid of the perfume packaging and therefore is only visible when you open it. Bödeker – who is also a passionate chess player – is referring to an event at the FTX Crypto Cup 2022: chess grandmaster Hans Niemann – the young man who appears as a brand ambassador in Bödeker’s commercials – had won there as the lowest-ranked chess player against the then world champion Magnus Carlsen. Niemann’s victory stunned the chess world and accusations were made that he had gained an unfair advantage by using vibrating anal beads.[1] Whether Niemann had really cheated or not, however, has neither been proven nor refuted to date. According to Niemann, his chess game at the time “spoke for itself” when he won. Applied to the perfume, CHESS should smell for itself – additional explanations of how CHESS actually smells are therefore superfluous. This provocative statement opens up several ways of looking at the relationship between concept and experience and the associated tension between art and consumer product in CHESS.

2.2 Between Art and Consumption

Anyone who decides to purchase the artwork is faced with the fundamental question of whether CHESS should be used as a perfume. Using seems obvious – after all, a perfume only comes into its own when it is used, worn and smelled. If not, it only has the potential to give off its scent, but no one will actually smells it. Unlike visual impressions, it is not possible for humans to recall odors from memory. It is therefore necessary to use the perfume continuously in order to obtain a new fragrance impression with each application. In this respect, CHESS tempts you to use it and consume it until it is used up – just like a consumer product. If you want to experience CHESS, the artwork transforms it into a consumer product. Can CHESS then still be considered an artwork? This dilemma is ironized on the packaging with the warning “THIS IS NOT A PERFUME! IT IS A WORK OF ART. DO NOT USE IT (as anything other than a decorative or investment object)!” The instructions for actual use (“Spray onto pulse from a distance of approximately 15 cm.”) can be found just below. The statement “THIS IS NOT A PERFUME” clearly is an allusion to René Magritte’s painting La Trahison des images – also known under the title This is not a pipe – and sets an art historical and theoretical context, which paradoxically opens up the possibility of questioning the status of CHESS as a work of art or perfume itself. The pop-up store staging of the exhibition, the advertising spots and the sale of the work lend CHESS the apparent character of a consumer good. At the same time, in the context of the art world, the advertising event becomes a performance that makes use of an advertising aesthetic and strategy in order to address it within the framework of the (art) exhibition.

The duality of CHESS is reminiscent of Andy Warhol’s Brillo Boxes (1964), which are reproductions of commercial packaging. Warhol produced numerous Brillo Boxes and sold them to art collectors and museums, making them, in a sense, mass consumer goods once again. Philosopher Arthur C. Danto sees Warhol’s Brillo boxes as a turning point in art theory, as they illustrate that two identical-looking objects can be judged differently: as art and as not art. Bödeker’s allusion to Warhol is evident in the stacked perfume packaging, which is reminiscent of the Brillo boxes. In contrast to Warhol, however, Bödeker does not resort to reproducing an existing object, but creates his own brand: Eau de Till.

2.3 Chess and Perfume

The link between chess and perfume forms the conceptual basis of Bödeker’s work. The combination of two fundamentally different spheres – the strategic game of chess and the sensual world of fragrances – is concretized in an object and creates a new space of meaning in its synthesis. Within the advertising for the perfume, chess primarily becomes an aesthetic that correlates in an associative-abstract way with the actual scent of the perfume.

CHESS is also a tribute to Marcel Duchamp, who stopped making art to devote himself entirely to his chess career. Bödeker alludes to Duchamp’s only surviving assisted readymade called Belle Haleine: Eau de Voilette (1920-1921). In this work, Duchamp used a perfume bottle from the Parisian company Rigaud and provided it with a label designed in collaboration with Man Ray. On it, the artist is depicted in the guise of his female alter ego, Rrose Sélavy. Belle Haleine is part of a series of readymades whose concept illustrates Duchamp’s consistent rejection of the traditional concept of art[2].

The scent of CHESS functions in the exhibition as a sensual fixed point that defies simple linguistic description. It is the result of a combination of different fragrances and must be experienced in order to be understood. The exact nature of the fragrance (according to the packaging, it is a combination of frankincense, ylang-ylang and peppermint oil) plays a subordinate role in the concept. The perfume therefore does not strive to smell like anything other than itself. CHESS smells like the CHESS perfume and thus becomes its own reference. The slogan “CHESS Smells For Itself” summarizes that CHESS emancipates itself from the game of chess in its reference and creates its own meaning as a brand and work of art.

Whether the scent of CHESS appeals to you or not is not decisive for its concept. Rather, the exhibition CHE$$ is characterized by its configuration of concept, form and content. Bödeker ties in with art-historical themes and debates on art theory and the boundaries of art. In doing so, he reaches the viewer on two levels: the intellectual and the sensual, which he brings together in CHESS/$$.

Cover image above the text: CHE$$ (2024). Photo: Maxi Lorenz.

[1] https://www.nytimes.com/2022/12/04/business/chess-cheating-scandal-magnus-carlsen-hans-niemann.html

[2] https://www.smb.museum/ausstellungen/detail/marcel-duchamp/

How to cite this article

Julia Frese and Till Bödeker (2024): CHE$$. w/k–Between Science & Art Journal. https://doi.org/10.55597/e9541

Be First to Comment