A conversation with Peter Tepe | Section: Interviews

Summary: Angelika Boeck is a visual artist who received her doctorate in Ireland – a border crosser between art and science. In the interview, her artistic development is first examined, with references to ethnology playing a central role. Then her dissertation project and its institutional background are discussed in detail.

Angelika Boeck, you are interesting for w/k because you work both artistically and academically, i.e. you transcend the divide between the two in terms of our definition. Firstly, could you briefly describe your development as an artist and academic: What and where did you study?

I studied interior architecture at the Academy of Fine Arts in Munich from 1986 to 1992, and sculpture as a master’s student of Professor James Reineking from 1992 to 1998. Between 2016 and 2019 I completed a doctoral programme at the Technological University Dublin.

At this time, what was your art practice like?

During my studies in interior design, I became interested in how my personality and the personalities of my fellow students are revealed in our individual answers to the same creative questions. Then, when I studied sculpture after my architecture studies, I used utility objects to artistically reflect on this issue. For example, for my work Sink (1992), I made three casts of washbasins out of soap and installed them in the apartments of three friends, replacing their own washbasins. I observed the individual traces of use as a kind of portrait. In addition, I observed the visible traces on twenty pairs of identical lace-up shoes that I provided for my fellow students, my professor, and his assistant, who all wore them for a year for my work Year (1993). My interest in the genre of portraiture became apparent quite early on, but it was only in retrospect that I became aware of it.

You consider the traces of use that the different individuals left on the washbasins, the lace-up shoes and possibly other objects as something that gives information about the respective individual, and insofar as a kind of portrait – in an extended sense of the word. Is that correct?

Yes, this attempt to expand the concept of portrait could be seen as a motivation for a significant part of my artistic work – but that was not clear to me from the beginning.

What have been your most important areas of artistic work?

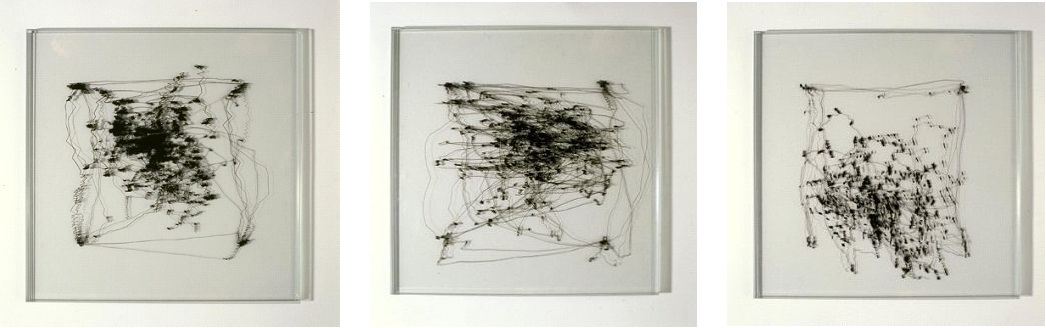

From 1995 to 2000, I was mainly involved with eye-tracking technology, and my pieces of work are internationally among the first artistic works using this technology. In all Eye Movement Recordings, a video camera that follows eye movements is connected to a computer that evaluates the visual data and translates it into visible lines and dots.

While at first I was interested in whether the eye movement drawings of different people form different, recognisable patterns when compare, and can thus be seen as portraits in the expanded sense explained above, I soon realised, however, that my main interest was in the interpersonal gaze dialogue, as well as our individual modes of perception, thought and interpretation patterns. Since the project StillePost [Chinese Whispers] (1999), I have been concerned with the question of how our self-image determines our representation of others; since 2005 with how the culturally different weighting of the sense organs shapes us and our understanding of others, how this understanding is expressed through cultural practices, and how these modes of perception and expression behave in contrast to visual perception and the traditional portrait.

Can you explain what StillePost is about?

It is my first intercultural experiment which I initiated in 1999 in the Republic of Côte d’Ivoire. Unlike my later projects, which focus on cultural practices based on senses other than vision, StillePost foregrounds seeing. The research hypothesis of the project was whether our own facial features determine the way we perceive and represent others, as Oscar Wilde asserts in his novel The Picture of Dorian Gray (1890):

“Every portrait that is painted with feeling is a portrait of the artist, not of the sitter. The sitter is merely the accident, the occasion”.

I decided to pass this question onto African artist colleagues from a living woodcarving tradition, as for my experiment, I needed project participants whose facial proportions differed from my own European ones. Also, my concept was based on the copy, and I was interested in the friction between the African understanding of a copy as a means of conserving meaning and the European concept of a copy as a forgery. The same applies to the bust, one of the most important European forms of sculptural portraiture barely found in traditional African art. I chose the Republic of Côte d’Ivoire based on a recommendation from Munich art dealer Arno Henseler, who gave me the shortest route description I have ever followed:

“In Abidjan take the bus to Boundiali. There you follow the road in the direction of travel to the crossroads by a large tree, and ask for the man whose name is on the note.”

However, that artist had already died.

How was StillePost created in this travel context?

The artist’s widow took me to Dramane Kolo-Zié Coulibaly, a sculptor colleague of her late husband, who I commissioned to make a portrait bust of me. Following the principle of ‘Chinese whispers’, I asked four African sculptors – one after the other and in different places – to copy the life-size wooden bust. Dramane’s sculpture served as a model for the second sculpture which was the model for the third, and so on, until with a series of five portraits – much earlier than I had expected – the bust showed an African woman. The artwork StillePost, which juxtaposes my photo portraits of the sculptors and their busts of me, shows both the metamorphosis of my portrait and the reflection of the African sculptors in it. Confirming Wildes’ proposal, the busts became more and more African as the artists subconsciously brought their own facial features into their copies.

If I have understood you correctly, the series is intended to be a confirmation of the hypothesis that the busts inevitably become more and more African through the process. Is that true?

Yes, it was conceived as an intervention that reverses and challenges the historical anthropological gaze. The method of mutual perception and representation that I developed for StillePost – as opposed to the traditional research hierarchy – generates reciprocity, so that the researcher is no longer perceived as the researcher and the other as the one being researched. Like all works based on this method, StillePost is part of the series Portrait as Dialogue, which I discuss later.

After finishing StillePost, have you developed and pursued an in-depth interest in anthropological questions, e.g. by reading academic texts from the discipline?

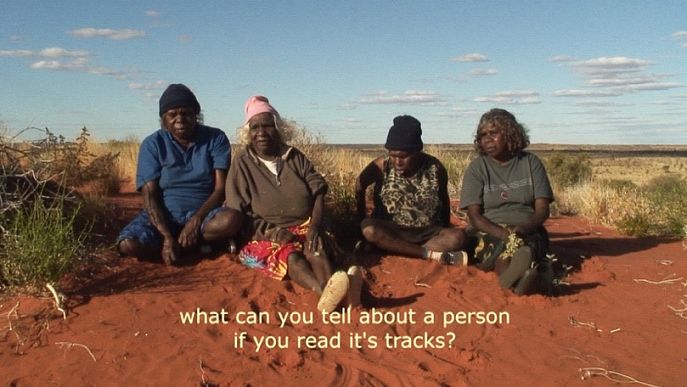

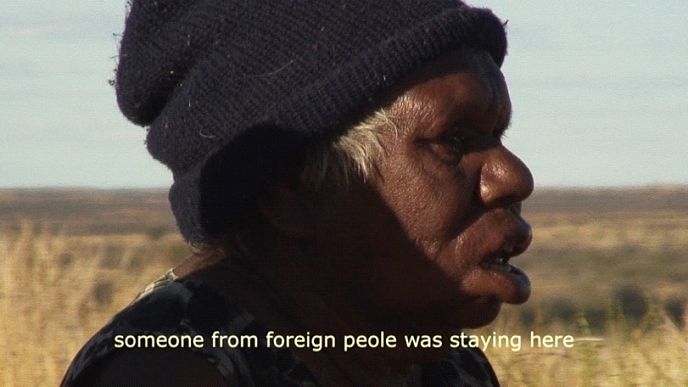

The then director of the Iwalewa House in Bayreuth, Tobias Wendl, who saw StillePost in my studio on the recommendation of anthropologist Bettina von Lintig, drew my attention to a study by Hans Himmelheber related to my work. In the early 1970s, Himmelheber, an Africa expert, commissioned artists from different carving traditions in the Republic of Côte d’Ivoire to carve a mask of himself in order to prove that African artists make portraits, which was opposed to the opinion of the majority of experts on African art at that time. What impressed me most was his observation that, with the exception of his wife, none of the Europeans to whom he had shown his masks recognised him, but that all Africans who saw them had no problem in doing so. The conclusion I drew from his observation had far-reaching consequences on my further artistic work. I wondered whether there are forms of aesthetic representation of people in other cultures that we, as Europeans, have not yet perceived due to our Western understanding of what a portrait is. This question has never left me, and since then I have read many anthropological texts and travelogues – and watched many documentaries focusing on this question. It was not easy to locate the practices that I explored in the following years in terms of their largely unrecognised potential as forms of aesthetic representation. For example, anthropologists who have studied the culture of Australian Aborigines, like the Aborigines themselves, classify tracking as part of the hunt, and hardly wonder about whether footprints can be seen as an extended form of the portrait.

For w/k you are of special interest since you have completed a doctoral degree after studying art in addition to your artistic activities. This is unusual for an artist. Let us begin with the facts: From when to when, where and under whose direction did your studies take place?

I started my studies in September 2016 and was awarded the degree of Doctor of Philosophy (PhD) in July 2019 from the Centre for Socially Engaged Practice-Based Research (SEPR) of the Technological University Dublin in the context of a PhD within the Prior Publication Programme. My PhD thesis entitled De-Colonising the Western Gaze: The Portrait as a Multi-Sensory Cultural Practice was supervised by Dr. Alan Grossman and Dr. Anthony Haughey.

What kind of doctoral study is it?

It is the professional supervision of a two-year practice-oriented dissertation. It requires neither the attendance of courses or seminars nor participation in examinations, but enables practitioners (filmmakers, photographers, visual artists, journalists, cultural managers, architects) who have not followed the traditional academic path to doctoral studies, to receive academic recognition for their practice-based research and published works. It is mostly similar to a cumulative dissertation which discusses several previously published research results.

How did this study come about?

From 2010 to 2016, I mainly lived in a small village in the central highlands of the island of Borneo (Sarawak/Malaysia). I used this secluded living situation to reflect on my previous artistic work by writing articles for various journals such as the Journal of Visual Art Practice, Culture and Dialogue or Critical Arts. Wolfgang Weileder, an art professor in England and friend of mine, advised me to do a doctorate and recommended that I look for a PhD within a prior publication programme in the Anglo-Saxon world, a programme which is not yet available in Germany. It was a lucky coincidence that I came to SEPR which was perfect for me with its focus on lens-based practice (photography, film, video) and ethnographic methods, as well as a focus on self-reflexivity.

Is this programme tied to concepts of artistic research?

This program is not only open to artists. In contrast to many doctoral programmes in the field of artistic research, which concentrate on the conception and realisation of a new work, the programme I completed in Dublin is aimed at established practitioners who want to reflect on their creative practice over the last ten years.

Is it thus a new form of doctoral studies, established only in a few English-speaking countries, that enables practitioners from various disciplines to obtain a doctorate through specific reflection on their own practical work?

That’s right. It is about reflecting on one’s own practice-based research, its publication and reception, as well as self-reflection.

Why was this reflection important to you?

I felt like I was becoming redundant. For me, it was about either completing this work and giving it a proper framework or – and I speculated on this – continuing to work on a new level with what I had achieved so far.

What does your dissertation deal with?

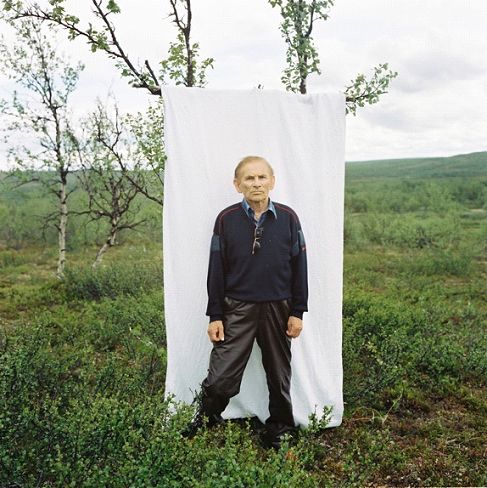

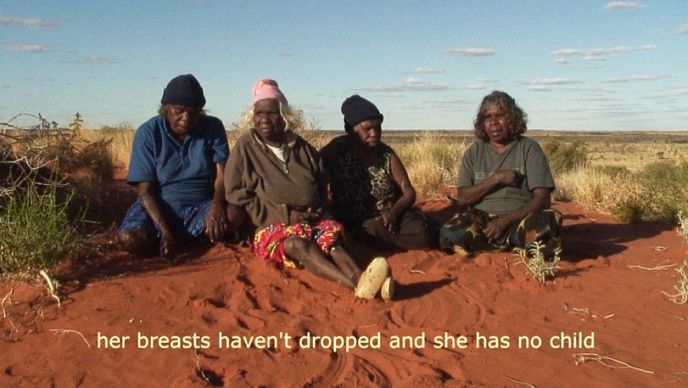

The aim was to identify and theoretically examine alternative methodological and analytical frameworks through which the Other can be represented. As an example, I analysed three out of a total of nine intercultural encounters during which I revealed myself to experts of specific cultural practices which I had interpreted as forms of aesthetic representation from my perspective as a Western artist and while they were doing the evaluation, they were also subject to my gaze. I was interested in cultural techniques that do not perceive people through their sense of sight alone and do not merely depict them visually. The Mongolian Tuwa, for example, prefer the sense of smell, the Australian Aborigines focus on vibration, and the Sami are interested in a person’s vocal and rhythmic expressions. In all projects, the portrait method, which I had already developed for StillePost, was used as a dialogue. While I – as a critical reference to historical anthropometric investigations, i.e. systematic cultural comparative surveying, photographic depiction or impression of human bodies – fixed the external appearance of the project participants through photo and video portraits, the Tuwa discussed how they assessed me on the basis of my body odor (Smell Me, 2011), the Australian Aborigines judged me on the basis of my footprints (Track Me, 2006), and the Sami composed a melody from their perceptions of me (Seek Me, 2005). The aim of all the works created within the framework of Portrait as Dialogue was to criticise the ocular-centered approach of Western representations of Otherness in order to expand the notion of portrait as a culturally-specific and multisensory practice.

What new insights have you gained?

Unlike scientists, artists don’t often take specific theories and scientific currents as their starting point. For me, it was about tracking down the formative artistic and scientific influences in a process of reverse engineering: the process of creating the artistic works is examined and placed in relation to the works of other artists, scientists and theoreticians in order to extract the components of what they consist.

I realised, for example, that my artistic research is not located between art and anthropology, as I had thought before my analysis, but in the area of Art as Anthropology, as Roger Sansi (2015) calls an art form in which artists deal with ideas and questions in which anthropology is also concerned.

I want to go back to the idea that anthropologists also deal with the Tuwa, the Aborigines and the Sami. However, it is not yet clear to me to what extent you deal with the same questions as anthropologists in relation to these societies, so that a distinction can be made between academic and artistic answers to the same question.

The crucial aspect of my methodology is the co-creative, intercultural interpersonal encounter in which the project participants and I perceived each other and expressed momentary perceptions in different ways by defining ourselves through the interpretation of the other. Of course, anthropologists, such as Johannes Fabian, also dealt with the theme of Othering – a process that constructs one’s own normality by distinguishing oneself from others. However, it is not customary for anthropologists to ask people whose practices they wish to explore to apply their practices to themselves in order to arrive at new insights in comparison to their own practice. With the exception of the American anthropologist Paul Stoller, who juxtaposed his perception of the Songhay in Niger with their sensory perception of his person, I know of no other example.

What difficulties did you encounter with your project?

The most important and difficult step for me was the realisation that my artistic practice is not quite as egalitarian and participative as I thought it was. In the post-production phase, I combined the material resulting from the intersubjective encounters – the interpretations of the participants (audio recordings, texts) and my photo portraits – into my artistic works. But only by taking this step was it possible for me to recognise the real strength of my research, namely that I had both undermined and reinforced the Western gaze which made the productive critical discourse about the interdependencies of self and other possible in the first place.

Would you have succeeded without the dissertation?

A critical look back at one’s own work is associated with self-criticism, and that is no easy undertaking – especially if one has had a certain idea for over a decade. Without the fundamental challenge and intellectual generosity of my highly motivated mentors, I would have barely managed to succeed.

Please briefly summarise your main results.

My research showed that my comparative intercultural art practice, which places me as an artist and researcher in a vulnerable position at the centre of the comparison of non-Western people and their practices as opposed to a historical-anthropological project of racial comparison, offers an unprecedented perspective of the examined cultural practices (e.g. the Sámis joik singing in Finnmark, the Australian Aborigines’ reading of traces or the veiling of women in Yemen). My project uncovered that these practices contribute to broadening the Western view of what constitutes a portrait – highlighting potential forms of aesthetic representation that as such have largely gone unnoticed and therefore unexplored. In contrast, my photographic representations of those involved in the project indicate what the Western gaze really is: a physiognomic representation. This juxtaposition is an original contribution to this field. In addition, the presentation and mediation of my works in controversial places of representation – especially the anthropological museum – have made an essential contribution to mental decolonisation, as demanded by theoreticians and curators such as Kebede (2004) and Hansen and Nielsen (2011). Finally, my artworks show a European who is a representative of the part of the world population that is not normally represented in these European collections – especially not as seen from a non-Western perspective.

How did the dissertation change your work?

I no longer intend to repeat versions of portrait as a dialogue in wider cultural contexts. Rather, I have understood that my many years of art practice entail a responsibility to both critically and creatively examine the process of decolonisation demanded by many anthropologists today. I would like to use my previous work as a basis for future works of art and writings that promote this project. It has also become clear to me that my intuition played a decisive role in my choice of topics even before I began to engage in academic theoretical discourses. I will follow my artistic intuition with even more confidence in the future.

What does the doctorate bring you, personally?

I have the impression that I have only really taken possession of my work through the dissertation. By this I mean that I have really understood it through the analysis and contextualisation.

Does the doctorate also have a professional benefit for you?

My decision to do a doctorate was not least due to the fact that my projects are relatively cost-intensive on the one hand, and not market-oriented on the other, which means I am dependent on subsidies. While academics in Germany can apply for research funding regardless of age, most programmes for funding artistic projects have an age limit. Through my doctorate, I have got around the expiry date that artists are subject to in this respect.

Angelika Boeck, thank you for this enlightening conversation. I would like to take this opportunity to announce a further w/k contribution from you, planned for 2020, which will deal with the funding situation for artists whose work moves between art and science.

Angelika Boeck’s dissertation entitled De-Colonising the Western Gaze: The Portrait as a Multi-Sensory Cultural Practice can be downloaded free of charge here.

▷ Website of the artist: www.angelika-boeck.de

Picture above the text: Angelika Boeck: Smell Me (2011). Photo: Wilson Bala.

References

Hansen, F., and Nielsen, T.O. (2011) Troubling Ireland – A Cross-Borders Think Tank for Artists and Curators with Kuratorisk Aktion. Available at: http://www.firestation.ie/programme/project/think-tank-programme/ (Accessed 13 October 2018).

Kebede, M. (2004) African Development and the Primacy of Mental Decolonization. Africa Development-Senegal, 29 (1): pp. 107–30.

Sansi, R. (2015) Art, Anthropology and the Gift, London: Bloomsbury.

Wilde, O. (1890) The Picture of Dorian Gray. Available at: https://www.amazon.co.uk/Picture-Dorian-Gray-Oscar-Wilde-ebook/dp/B000JQU4TW ( Accessed 4 January 2017).

How to cite this article

Peter Tepe (2019): Angelika Boeck: Artist with Doctorate. w/k–Between Science & Art Journal. https://doi.org/10.55597/e5117

Be First to Comment