Was this change intended to be a definite goodbye to the fine arts?

No, it was meant to be a longer transition period: I wanted to pursue my philosophical and later also the increasing literary interests in a more intensive way, at least for a certain period of time, in order to then go back to visual arts with some kind of a broadened horizon. I had neither planned nor wished this phase to become steady.

Why did you choose German philology as a second subject?

I made this decision because during my art studies, I had read many literary texts from different national literatures with great interest and benefit.

Was your reorientation encouraged by certain people?

I think that German philologist Herbert Anton, who had himself a strong philosophical orientation, eventually enabled me to pursue a decade-long university activity – a stroke of luck I will never forget. It has determined my life. He actually accepted to take a former art student with a PhD in philosophy under his wing and supported me in a way that later allowed me to become adjunct professor at the department for German philology.

How would you describe and classify phase 3 of your artistic career?

During my first semesters at university, I concentrated on philosophy and German philology, but my artistic activity continued to simmer on a low flame.

Perhaps we should call this the elementary form of a scientist/artist (the artistic activity was somehow accompanying the scientific one). This did not change so much during the doctoral phase. Though, keep in mind that unlike normal graduate students, postgraduates actively contribute to scientific research. Thus, I would suggest to call this the second stage of development of a scientist/artist (an artistic activity that accompanies a PhD project).

From 1976 to 1988, I was totally committed to teaching and research in German philology and philosophy so that there was hardly any time or energy to continue the artistic work. I created just some drawings and a few sketches for projects.

Throughout your longstanding teaching activity at the German department and at the philosophical institute, have you ever offered seminars and classes that dealt with issues from aesthetics and philosophy of art?

Yes, but other topics were predominant. Over time, my earlier interest in art theory and aesthetics turned into an interest in literary theory and methods of text analysis. As I was not – apart from some minor experiments[4]> in earlier times – pursuing any literary activity myself, there was no direct link between my new theoretical interests and my artistic work. My dealing with literature had scientific and cognitive objectives and I got familiarized with innovative theory-building.

Phases 4 and 5

What about Phase 4?

After my habilitation in philosophy and the foundation of the study and research focus, my artistic activity flared up again: first, I created many works, most of which can be categorized as object art. Secondly, in collaboration with visual artist and musician Chris Scholl, I undertook an experiment in installation art which we are going to speak about later. Thirdly, I integrated artistic elements into my scientific teachings and publications.[5] Thus, it is actually only in phase 4 that I started working as a border crosser between science and fine arts.

How do you explain the flare-up of your artistic activity during that phase?

If your center of life once used to be an artistic activity, you are very likely to develop – provided that the general conditions change in your favor, for example by establishing a stable professional life − the desire to reactivate your former passion. Resuming your artistic activity then helps you to restore a state of equilibrium between the different parts of your personality: What once used to be very important but had then been set aside, is now being revived under different circumstances. The reintegration of what had been split off was and still is of great importance for my life, and I guess that other border crossers and scientists know this experience. By the way, what I am doing here in order to give you an insight into my career is basically retracing correlations, I do not want to evaluate anything. Whether a scientist/artist has been scientifically or artistically innovative is another kettle of fish.

And how do you define phase 5?

This phase in a way finally resumes phase 4 after a seventeen year long dry spell. However, it is limited to paintings / pictorial objects and works on paper. Already in the preceding years I had stopped using artistic elements in my university classes. On the other hand, phase 5 is the moment when I started my publishing and organizational activity for w/k. Working on this project, it has always been important for me to guarantee scientists/artists like me a space in it.

Some more about the different phases of artistic development

I think we should have a closer look at the different phases of your artistic activity. Please describe what exactly you did in the different phases.

In phase 1, my works are influenced by different artistic movements, such as for example Art Informel, Abstract Expressionism and Art Brut[6]; besides I dealt with the works of Willi Baumeister, Antoni Tapies and several other artists. I suppose that Karl Otto Götz accepted me in his class just because of these stylistic influences, which had shaped my portfolio.

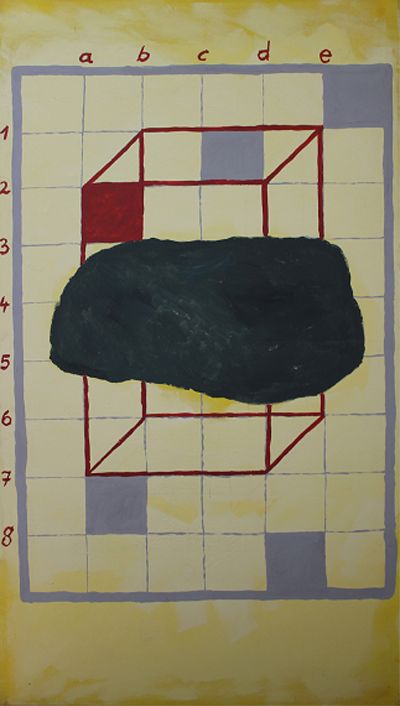

In Götz’s class, though, I did not continue on this line, but entered phase 2, which stood under the influence of contemporary movements such as Land Art and Minimalism – a new path that simply forbade everything picturesque. From the very first semesters I developed quite an autonomous artistic program. One of my aims was to play with the relation between spatial-perspectival and flat visual perception – especially with the moment in which the one turns into the other. Doing this, I stuck to a principle that can in a certain sense be called minimalist: “Choose as simple means as possible to do what you want to do and drop every kind of accessory and decoration.”[7]

During phase 2, I created several series that are more or less linked with the mentioned artistic agenda. One example would be the pictorial objects with wire constructions, which are fixed on chipboard panels.[8] In phase 3 I referred back to these works with some works on canvas that deal with the construction and destruction of spatial illusion and order in general in a different way. Still sticking to minimalist principles, I worked with simple tinting paints and avoided all kind of accessories and decoration.[9]

Did this change in phase 4?

Yes, it did. In phase 4, I created a bigger number of pictures / pictorial objects. On the one hand, I continued to use elements that had already proven to be effective in phase 2 (simple chipboard panels as a basis, wire and clothesline as covering strings, ordinary screws for the fixation and so on). On the other hand, I added new components, which were biographically connected to my years of study. In those years, I had read Kant’s Critique of Pure Reason, Fichte’s Theory of knowledge, Hegel’s Phenomenology of Spirit and many other texts of the so-called German Idealism as well as contemporary texts discussed at that time, such as texts of the Frankfurt School, Critical Rationalism and Analytical Philosophy or last but not least Ludwig Wittgenstein and his successors. After reading I excerpted them, first by hand and later on a typewriter. These as extensive as intensive readings were pushed forward by the need to find my own philosophical standpoint, which I would be able to defend in good conscience. As I have already said, I was particularly interested in the development of thought from Kant to Fichte, Schelling and Hegel, whose writings I then experienced again during my “metaphysical phase”, copying, mentally analyzing and rewriting them.

This means that you incorporated parts of your several-hundred-page-long collection of excerpts into your pictorial objects. Did this have any consequences?

The works became much more complex compared to the ones from phase 2 and 3. I abolished the minimalist limitations maintaining all the same the element of minimalist construction. In 1992, I described the style of these layer pictures as follows: “Every picture is composed of a great number of layers, usually about five to ten different ones. The uppermost layer is made by strings, wire and plastic cord. Many pictures contain a layer of text, which is composed of earlier manuscripts or typewritten excerpts. For the other layers, I might use cardboard, plastic foil and other materials of this kind. In some pictures, I work with the glass from simple interchangeable picture frames, which I then paint over with varnish. I make the different layers permeable by ripping and cutting them open. Generally, I prefer to work in smaller series of three or four pictures. In terms of content, the common reference of such a series is often a photo the enlarged black-and-white photocopy of which will appear in every work as a kind of key theme entailing variations.”[10]

By using excerpts that you wrote as a student or during your doctoral phase, you established a connection with your scientific activity.

That’s true, but these links do not refer to the content of Kant’s, Hegel’s or Fichte’s arguments and theses, I definitely do not refer my work to the theories these philosophers have developed – the excerpts rather represent playful components of an intuitive and improvisational artistic strategy.

An important highlight of phase 4, undoubtedly, was the “action event” Setzen – Zusammen – Setzen. Dreieck Kunst – Philosophie – Musik (Triangle Art – Philosophy – Music), which you organized together with Chris Scholl at Werstener Kulturbunker in Düsseldorf and for which there is even a small catalogue. What exactly was your contribution to this event?

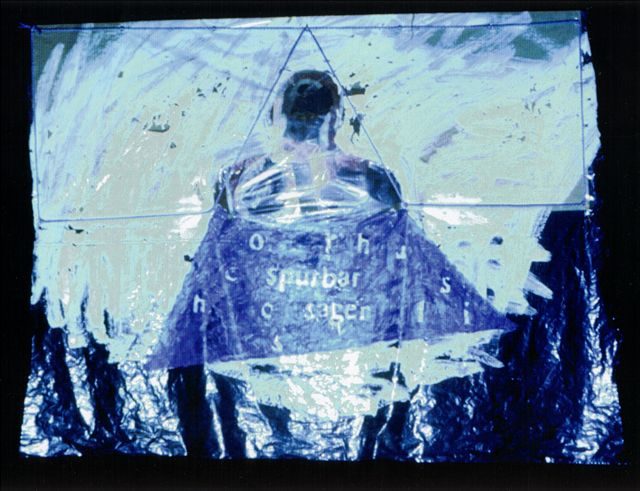

Firstly, I showed some pictorial objects in the staircase, secondly, I put up an installation that Chris Scholl and I had developed together. It was composed of several triangular and pyramid shapes. Additionally I painted − live and on site – parts of a big plastic foil that belonged to the installation. Last but not least, I presented my new book Postmoderne/Poststrukturalismus[11] during the theoretical and philosophical part of the evening. The musical part contained a performance by the drumming group Drums off Chaos, which included well-known musicians such as Frank Köllges (founder of Härte 10 and Intermission, who should pass away long before his time) and Jaki Liebezeit (who many might know as the percussionist of the famous band Can).

A passage from the presented book was projected onto the plastic foil and during the painting action, I modified and manipulated the text in a way that in the end nothing apart from some single letters and the two words “spürbar” (tangible, perceivable) and “sagen” (say) was left. Later, I would integrate this part of the foil into a pictorial object, which was then, in 2001, used for the cover of my book Mythos & Literatur, published in 2001.[12]

Connections between the scientific and the artistic activity

Is there a link between the chosen words and your scientific work?

There is a connection between these words and my scientific activity indeed, a connection that concerns this time the meaning of these words, whereas, as you probably remember, the link to my scientific activity established by the excerpts was merely formal. I had chosen the projected text passage while randomly leafing through the book that I should present during the event. The words “spürbar” and “sagen”, which were used in different lines of the text, immediately caught my eye and I found it a good combination of words to express one of my ambitions in scientific work: I always wanted the things I said in a class or wrote in scientific text to become “spürbar” (tangible, perceivable). I wanted them to touch the audience or the readers and encourage them to change certain aspects of their way of thinking and acting.

Another highlight of phase 4 is your performative lecture Mythisches, Allzumythisches (Mythical, all too mythical), which you held in winter term 1993/94 and which has been published in book form. It was probably the first academic lecture in form of a stage-play.[13]

I think that only a person with a strong artistic character trait will have the courage for a term long scientific and artistic experiment of this kind. Furthermore, it must be a phase when the artistic part of this person’s soul is somehow “volcanically active”.

Why did you not continue your activities as a scientist/artist after 1995?

At that time, the workload at university became bigger and bigger – partly because of what I had imposed to myself by creating the focus, that is teaching, examination, research and publication, and by committing myself to the reform of the German philology courses in Düsseldorf[14], which turned out to be very time-consuming, partly because of the objective general conditions under which academic work took place at that time and especially after 2004, when the two-cycle system was set up. The artistic part of my personality was pushed into the background for more than 17 years. Similarly to what had happened after the end of phase 3, I just created a few drawings and sketches during the little spare time I had.

Have you also tried to find suitable names for the artistic strategies you worked with during phases 1-4?

Yes, and this is the preliminary result:

Phase 1 (1965−1968): Informal material pictures – “informal” in the specific sense I have already explained.

Phase 2 (1968−1970): Minimalist constructions (objects and pictorial objects with materials such as wire, string and clothesline). If I use color here, this does not happen in an ‘artistic’ but in a rough way.

Phase 3 (1970−1975): Constructions on canvas, painted in a minimalist style.

Phase 4 (1989−1995): Fusion of Informalism and Minimalist constructions (Informal Construction). During this period, I developed several ways to conceive a series.

How to cite this article

Peter Tepe (2016): Border Crosser between Science and Visual Arts. w/k–Between Science & Art Journal. https://doi.org/10.55597/e1610

Be First to Comment